November 17, 2023, by Laura Nicholson

Medicine and Health Sciences Faculty Takeover: The Immersive Suite

Throughout the 2023-4 Academic Year we are running a new feature on the LT blog, a Faculty Takeover month! Each month (excluding December) we will feature posts from a different faculty at the University. Every Friday, posts will highlight interesting work and ideas related to technology in teaching and learning and showcase unique projects from within the various disciplines across UoN. In October we had our Faculty of Science Takeover, this month we are promoting Medicine and Health Sciences.

In the post below, Gill Langmack, Assistant Professor in Health Sciences, reflects on the benefits of using an immersive suite to enhance the learning experience.

Engaging students in learning: adding value by using an immersive suite

How we present teaching material to students influences how students learn. So, if we can increase the interaction between the student and the information presented, it can improve engagement and a motivation to learn.

In terms of learning theory, using an immersive suite typically supports constructivism (Marougas, 2023) and situated learning (Lave and Wenger). Depending on the learning objectives set, the session may focus on practically undertaking skills within the environment, and developing professional behaviours, or using what is presented to explain, analyse and even generate new knowledge and understanding. Where a session utilises a scenario-based approach, e.g. simulation, it will typically culminate in a facilitated debrief. Thus the debriefing session will provide additional learning opportunities to reflect on the experiences and to scaffold learning (Vygotsky; Schon, 1983).

Immersive suites:

Within the University of Nottingham, Faculty of Medicine, Clinical Skills Unit, based in Queen’s Medical Centre, there are two immersive suites. Each of the two small rooms, approx. 6m2 (20ft2), has retractable walls, which when opened, create a small immersive room within a larger clinical skills room. Projectors then project the environment (including static/360 images or videos) onto 3 sides of the room. The 4th side is open to any observers. Particularly in larger groups, both undertaking and observing scenarios are key elements of developing understanding through discussions within debriefing sessions.

Using the immersive suite

What the immersive suite provides, is a way to augment reality. So, whilst the immediate thought is to use the immersive suite in creating practical simulations, it can be used in multiple ways. In designing the teaching material there are several key aspects to consider when setting up the session, including:

-

Static sessions

Familiarising students with the technology prior to running more complex sessions helps to reduce potential worries with what is a very different teaching modality. Thus adding static images as a background to explore, such as x‑rays; providing short videos or sounds that play; and/or adding questions to answer within the technology enables interaction with the technology and can help students to overcome potential anxieties with the technology.

-

Creating authentic environments

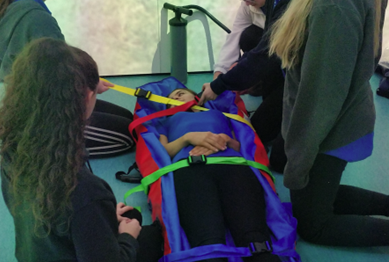

Even without using the interactivity afforded by the immersive suite technology, delivering simulations in the immersive suite still provides environmental authenticity, particularly if it includes video and sound, helping the student to engage in the learning. Providing environmental cues therefore bridges the gap between running a practical simulation in a classroom and running exactly the same situation ‘in situ’, in clinical practice.

Providing the noises, and the ‘hustle and bustle’ that surrounds the student working in clinical practice can help to increase the student’s ability to role-play the scenario providing an appearance of reality, but without potential patient safety concerns of practising in the clinical setting. But including the video and sound can potentially distract from the running of the simulation through increasing the cognitive load and students experiencing high levels of stress so reducing learning (Mills et al., 2016). In Mills et al’s (2016) research, however, despite the additional sounds increasing stress levels, it also prompted students to respond positively in contextualising and applying their knowledge and skills to develop their understanding within what they perceived as a typical professional working environment.

This suggests that rather than strip extraneous information from a scenario to reduce cognitive load, where augmented reality provides context, the increased environmental cues provide a way to develop professional resilience. For the teacher developing the scenario though, there remains, a balance to be made in how much extraneous information is included. This is dependent on a number of factors, including learning outcomes, the appropriateness of using the immersive technology to deliver the information and the relative experience of the student.

-

Interactivity: what and how much to use?

Utilising the interactivity afforded by the immersive technology, increases an ability for the lecturer to ‘step back’, which increases student-led learning, and enables the student to control how they access and analyse information. Thus students develop abilities to reason through information, develop judgements and develop justifiable decisions in a situation.

The software program used within the immersive suite allows the use of hotspots to be added, leading to further information (words and images/video), or questions being presented. Clicking on these within the teaching session, then enables a scenario to move forward. Hotspots can therefore be set up to consolidate key learning points, to trigger discussion, or to move the scenario forward. Once the scenario is set-up, the student can potentially take control and follow the scenario in their own time.

-

Dynamic scenarios

Changing backgrounds can help to move scenarios on within a simulation. Thus the scenario can start in the pre-hospital environment, move into the Emergency Department and on into a critical care area, or operating theatres, depending on the narrative set. The immersive suite is therefore a way of creating learning environments that may not easily be accessible to students, yet still providing a way of developing experiential learning.

The immersive suite can therefore support an ability to construct learning through the application of prior knowledge, allowing direct engagement with the information.

Barriers to overcome …

There are several issues to address when considering including the immersive suite within teaching students:

- How to use the technology effectively with large groups.

- Finding images to use that are copyright free and are appropriate to use.

- Images project at an increased size, so people on images can appear too large for the situation.

- Taking your own images to use is an option, but these need to be taken from knee level, not eye level, so when projected, the student is not looking down on the situation, but is at the same level as the images.

- Learning to use the software program – this can take some time, but help is available.

- Scheduling time in the immersive suite, thus repeatability and ease of access to the learning may be an issue.

Other uses

As a form of augmented learning, the immersion suite provides situational awareness. Thus, it has also been used to understand how spaces are used, for example, Torres-Landa et al (2019) set up a Styrofoam life-sized model of an operating theatre, undertaking a series of scenarios to evaluate how the space is used, prior to investing money and constructing their operating theatres.

What next?

We know that just providing the information is insufficient, it’s what the student then does with the information that matters (Biggs, 1999). Augmenting and enhancing reality through merging physical and virtual spaces, provides a hybrid, dynamic environment which is accessible in real-time. Typically, it is enjoyed by students engaging the student’s curiosity to find out more about the information being presented..

If you are interested in finding out more about training in using the Immersive Suite, then do get in contact with myself gill.langmack@nottingham.ac.uk, or email Emma Davies (staff) mzzed@exmail.nottingham.ac.uk

Links

- Clinical Skills SharePoint page

- Immersive Interactive (the current software used in the QMC immersive suites)

References:

- Biggs, J. (1999) What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57-75.

- Laurillard, D., (2012) Rethinking University Teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marougkas, A., Troussas, C., Krouska, A. and Sgouropoulou, C., (2023) Virtual Reality in Education: A Review of Learning Theories, Approaches and Methodologies for the Last Decade. Electronics (Switzerland) 12(13)

- Mills, B.W., Carter, O.B., Rudd, C.J., Claxton, L.A., Ross, N.P. and Strobel, N.A. (2016) Effects of Low- Versus High-Fidelity Simulations on the Cognitive Burden and Performance of Entry-Level Paramedicine Students: A Mixed-Methods Comparison Trial Using Eye-Tracking, Continuous Heart Rate, Difficulty Rating Scales, Video Observation and Interviews. Simulation in Healthcare: Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. February 11(1), 10-18.

- Schon, D (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: how professionals think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Torres-Landa, S., Neylan, C., Quinlan, K., Klock, C., Jefferson, C., Williams, N. N., Caskey, R. C., Greulich, S., Kolb, G., Morgan, C., Mahoney, K. and Dumon, K. R., (2019) Interprofessional Simulations to Inform Perioperative Facility Planning and Design. Journal of Surgical Education 76(1) 223-233.

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. MA: Harvard University Press.

Calling all blog volunteers!

Would you like to promote how technology is being used in your faculty? Maybe you have some students who are also keen to share how technology has enhanced their learning experiences? If you are interested in submitting a blog post about your use of technology for teaching and learning, please do get in touch. Find out how to submit a post, or arrange to have a chat about ideas

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply