August 26, 2020, by Lynn Fotheringham

Manual labour and war on Helots

CONTENT: ANCIENT SLAVERY, MURDER OF THE ENSLAVED, IMAGES IMPLYING VIOLENCE

Three, by Kieron Gillen & Ryan Kelly; chapter/issue 1, cont. [For an introduction to Three, see this post.]

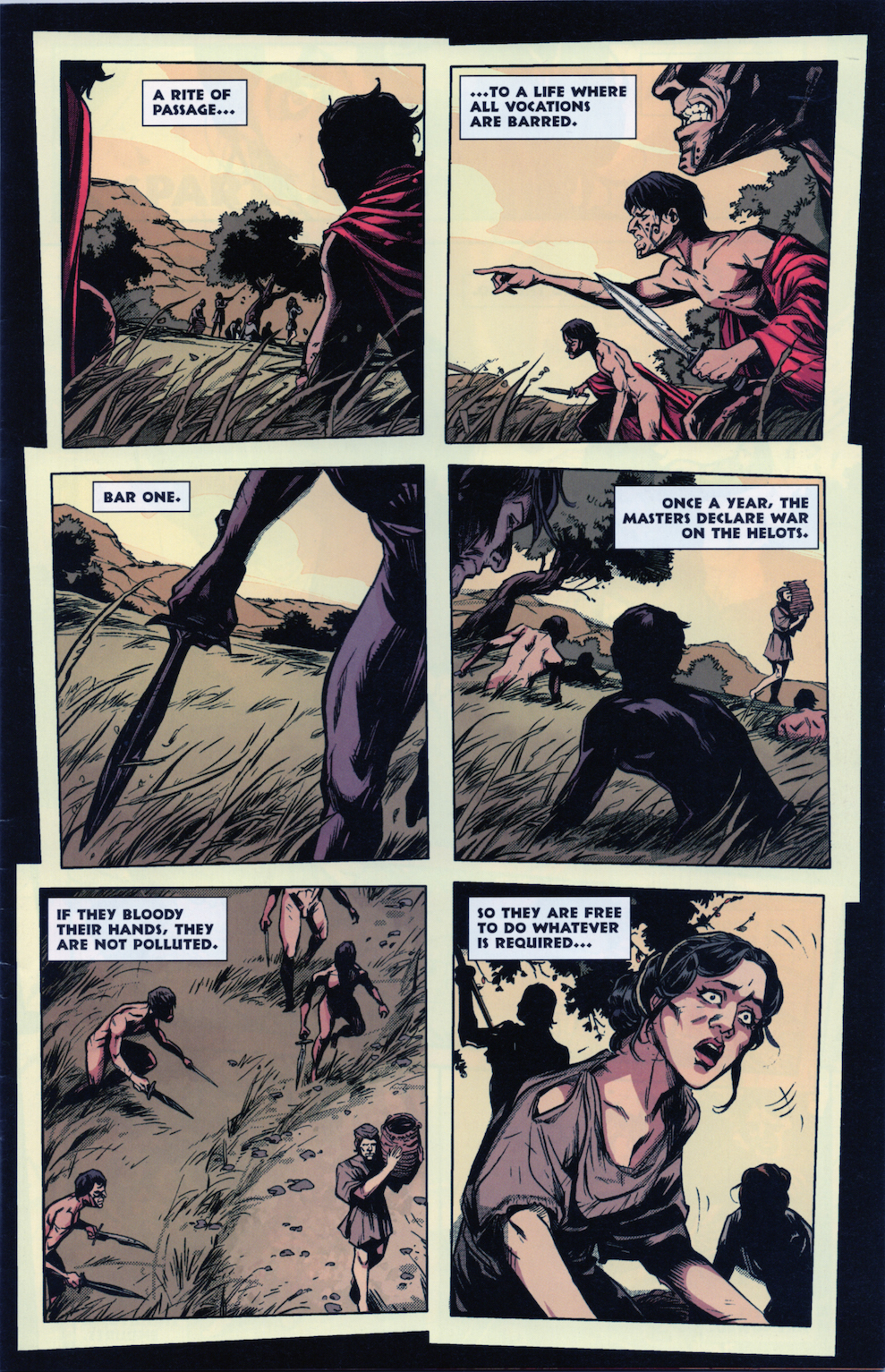

This page comes between the panel shown in the post, The Krypteia, part 2, and those shown in The Krypteia, part 1. The term ‘rite of passage’ picks up on the interpretation of the krypteia as a potentially ritual practice. The panels on this page are already beginning to float free from the right-angle grid, anticipating the more extreme disruption on the following page. Ryan Kelly’s expressive manipulation of page-layouts, including clever use of borders/gutters, continues throughout the book.

THREE ch.1, p.3

Two points made in the captions here can be tied directly to one source: Plutarch’s Lycurgus. I’ll start with the second point, which comes from the same section that deals with the krypteia:

Once a year, the masters declare war on the Helots.

If they bloody their hands, they are not polluted.

28. (4) Ἀριστοτέλης δὲ μάλιστά φησι καὶ τοὺς ἐφόρους, ὅταν εἰς τὴν ἀρχὴν καταστῶσι πρῶτον, τοῖς εἵλωσι καταγγέλλειν πόλεμον, ὅπως εὐαγὲς ᾖ τὸ ἀνελεῖν. |

28. (4) And Aristotle in particular says also that the ephors*, as soon as they came into office, made formal declaration of war upon the Helots, in order that there might be no impiety in slaying them. |

- Text and translation by Bernadotte Perrin, Loeb Classical Library vol. 46, 1914.

* The ‘ephors’ were annually elected magistrates.

Although Plutarch may be connecting the ‘declaration of war’ with the murderous actions of the krypteia, mentioned a couple of sentences earlier, the section as a whole includes a wide variety of information – including the story about forcing the Helots to get drunk. So the declaration of war could reflect a more general willingness to kill Helots.

Further up the page, we read:

… to a life where all vocations are barred.

Bar one.

This goes back to an earlier section of the Lycurgus:

24. (2) καὶ γὰρ ἕν τι τοῦτο τῶν καλῶν ἦν καὶ μακαρίων ἃ παρεσκεύασε τοῖς ἑαυτοῦ πολίταις ὁ Λυκοῦργος, ἀφθονία σχολῆς, οἷς τέχνης μὲν ἅψασθαι βαναύσου τὸ παράπαν οὐκ ἐφεῖτο, χρηματισμοῦ δὲ συναγωγὴν ἔχοντος ἐργώδη καὶ πραγματείαν οὐδ᾿ ὁτιοῦν ἔδει, διὰ τὸ κομιδῇ τὸν πλοῦτον ἄζηλον γεγονέναι καὶ ἄτιμον. |

24. (2) For one of the noble and blessed privileges which Lycurgus provided for his fellow-citizens, was abundance of leisure, since he forbade their engaging in any mechanical art whatsoever, and as for money-making, with its laborious efforts to amass wealth, there was no need of it at all, since wealth awakened no envy and brought no honour. |

- Text and translation as above.

The idea that Spartans were explicitly barred from certain activities is sometimes paraphrased in terms such as: ‘they were the only professional soldiers in Classical Greece’ – but ‘professional’ is an anachronistic concept for this period. Looking down on both manual labour and making money through business/trade is a characteristic of aristocracies throughout history; they already have wealth in terms of land, as the Spartiates did. Going to war was the civic duty of leisured gentlemen in all Greek cities; the Spartans apparently took some unusual steps to ensure their leisure, but these steps were ultimately ineffective, partly due to greed for (land-based) wealth. This will come up again in ch./issue 3.

NOTE: I may refer to/quote comments on this post either in later blog-posts or in a research publication. More information about my audience-research, including a Privacy Notice and ways of getting hold of the book.

Extracts from Three © Kieron Gillen & Ryan Kelly. Used with permission.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply