July 25, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

CRISPR – and the race is on (again)

At the weekend I was reading an article in the Guardian about a team of Chinese scientists trying to use CRISPR/gene editing for the treatment of cancer; and I sighed. The article contained some of the standard and, I believe, quite worn-out tropes that pepper coverage of advances in biotechnology: playing God, designer babies…, as well as the ‘science is a race’ metaphor. In this case the race is on about who’ll be the “first in the world to inject people with cells modified using the CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing technique”, as David Cyranoski put it in a less metaphorically laden Nature article on which the Guardian one was based. Will it be a US team? Or will the Chinese team “beat them to the punch of being the first of its kind”, as the Guardian article put it? There are some worries though about this ‘race’, as Cyranoski reports, quoting a bioethicist: “China has had a reputation for moving fast — sometimes too fast — with CRISPR, says Tetsuya Ishii, a bioethicist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan.”

Reflections on a stem cell race

This reminded me of the stem cell and cloning race that unfolded in the early 2000s, about a decade ago (and on which Cyranoski has reported between about 2004 and 2014). The circumstances of this race were quite different, but I think we might still want to learn from it in terms of how to think about science, scientists and responsibility.

Between 2004 and 2005 there was a race between two teams of scientists, one team working in Newscastle (UK) and the other in Seoul (South Korea). The prize was being first in achieving a breakthrough in stem cell therapies based on therapeutic cloning. That race did not end well, as we know, especially for the South Korean team led by Woo Suk Hwang, a cloning specialist initially celebrated as a pioneer and hero.

This episode in the history of stem cell research provoked some soul searching amongst scientists and science writers about framing scientific research as a race. In 2006 the Science Media Centre quoted some UK scientists who had been involved in the race. Professor Colin McGuckin (Professor of Regenerative Medicine, Stem Cell Institute, Newcastle University) said: “Stem Cell technology should not be a race – we have to get it right!”. David Macauley (Chief Executive, UK Stem Cell Foundation) emphasised: “This is not about who will be first to ‘win the stem cell race’”. Alison Murdoch, the then leader of the British team, said in interview with the BBC: “I don’t think it’s particularly helpful to think of this as actually a race between scientists to achieve the end because what really matters is making sure that the technologies will get there to give treatments to people, in the long run….”.

And finally, in an article for the BBC the late Lisa Jardine, pointed out: “So the expectations on the part of doctors and patients, and the government and commercial pressures on scientists working in this field are enormous. The pressure from the South Korean government – determined to be right at the forefront of technological and scientific innovation – for some dramatic pay-off, was extreme.”

I think it might be good to listen to these voices again, especially in a context where the race trope has been joined by the ‘impact’ trope. Scientists are increasingly expected to generate results, especially results that can be translated into sell-able treatments and patents.

Science as a race

Conceptualising science as a race has a long history, rooted in the 19th century belief in the progress of science. But things, especially in genetics, genomics and synthetic biology, have become tougher over the years. As Hub Zwart has pointed out, in a chapter on “Professional ethics and scholarly communication”, James Watson, one of the discoverers of DNA, advocated the idea of science as a race in his 1968 book The Double Helix. “He simply changed the rules of the game. Rather than obeying the old rules of courtesy, collegiality and openness (or even intellectual communism, as Robert Merton called it), he promoted new methods such as competition and secrecy.” Of course, Watson was not alone in this. Many developments have begun to threaten an ideal of science as transparent, open and honest; and the same goes for science communication.

As Bernard Schiele pointed out in an interview a decade ago: “Sciences today are increasingly subject to the need to produce innovative developments, as these are needed to maintain a level of output or commercial production.” This pressure is certainly evident in the context of synthetic biology, of which CRISPR research is a part. At the same time, there are, as Schiele says, “changes in the profession of journalists, who must now make their mark within an economic structure that is integrated and globalised as never before” and, more recently, changing rapidly in the context of social media use.

Science, pressure and responsibility

In the process of producing and communicating ‘innovative developments’, scientists and science communicators have to engage in what one might call ‘expectation management’. Creating expectations and making (even hyping) promises is crucial to providing the “dynamism and momentum upon which so many ventures in science and technology depend“.

Dynamism and momentum are fine. But do we need to engage in a race where there are winners, losers, casualties and so on; where all that counts is speed? Could the race for funding, publications and impact threaten this very dynamism?

Echoing Lisa Jardine, Jeffrey Helm, a scientist and science writer, reflected on such issues a decade ago: “Doing biological research is not cheap, it takes time and money, and there is not enough of either to go around for everyone to fulfil their Nobel Prize dreams. If a scientist wants stability and adequate funding, i.e. a career, they have to produce. But these days knowledge is not enough; it has to be something that can turn into a ‘breakthrough’, a patent, or a pill. The pressure to produce, and for experiments to ‘work’ can be enormous. Scientists can break under that pressure, having worked in many different research labs I have seen it happen. Although it may come as a surprise to some, scientists are only human.”

Do we sometimes forget that scientists are human? Do we, even more frequently, forget lessons we could learn from the past about how to do or not to do science and treat or not to treat scientists? Do we consciously or unconsciously think we can use Responsible Research and Innovation as a magic wand to ward of the problems we create when we make racing to be the first a scientific norm and trying to win the race the new scientific normal? We all have a responsibility to make science work and to make it work for us, but we are also responsible for how we treat the workers.

And here is a brilliant SONG recommended by @Huwtube Race for the Prize by The Flaming Lips!

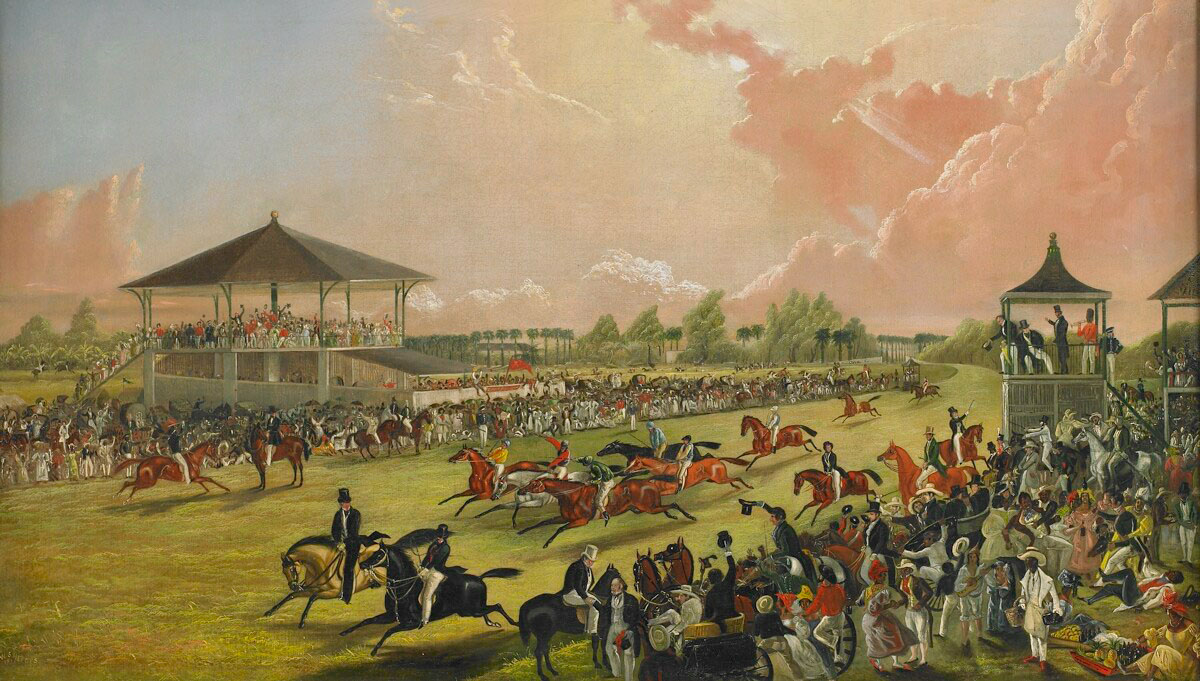

Image: Horse racing at Jacksonville, Alabama, 1841

I am pleased to read the article on your Web site, the information is very interesting to see. Cara Mengobati Tumor Otak