August 5, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

The epigenetic muddle and the trouble with science writing

I have been interested in epigenetics, especially public portrayals of epigenetics, for about six or seven years. About three years ago I tried to get some funding to examine emerging and changing meanings of epigenetics in traditional and new media (including what one might call ‘alternative’ media), but unfortunately never got the funding. When writing the proposal, my collaborators and I thought we knew what epigenetics generally meant and how it fitted into the genealogy of genetic and genomics; ‘epi-genetics’ went, it seems, ‘above and beyond’ genetics and dealt with gene expression or gene regulation. There were even popular books being published on the topic and things seemed to be relatively settled. But obviously things were not that simple.

When writing our proposal, we also observed that an increasing number of social scientists, philosophers and historians of science had begun to write about epigenetics, some seeing it as a friend in the fight against a perceived ‘genetic determinism’ displayed in genetics; others seeing it as ‘genetic determinism’ in disguise. Some began to make rather grand claims, including that epigenetics signalled a revolution or crisis in science, that it was overturning the central dogma of molecular genetics, that it was replacing the established theory of evolution, and that, given some indications of possible transgenerational inheritance, epigenetics signalled a return to Lamarckism.

Such claims were not left unopposed. Jerry Coyne in particular wrote various blog posts (on his blog Evolution is True) challenging these emerging statements in 2011, 2012 and 2013. In terms of a return to Lamarckism, papers challenging this assumption are still being published, most recently an article by Ute Deichmann entitled “Why epigenetics is not a vindication of Lamarckism – and why that matters”.

However, over the last ten years or so one can also observe a general shift from breathless excitement, grand claims and hype to more nuanced, modest and humble assessments of what epigenetics is and what it can achieve. But there are still surprises in store, especially when it comes to communicating epigenetics.

Communicating epigenetics – difficulties and pitfalls

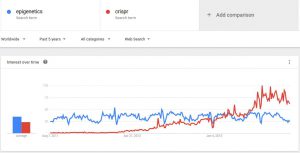

Epigenetics as a field or topic hasn’t yet had its Dolly or its ‘Human Genome has been Deciphered’ moment, and as this Google trend graph shows, it is now being overtaken by public interest in CRISPR. This is not bad, but it doesn’t make it easy to write about  epigenetics for a popular audience. The question is: how to grab attention without over-hyping certain aspects of a science and without down-playing important uncertainties and ambiguities.

epigenetics for a popular audience. The question is: how to grab attention without over-hyping certain aspects of a science and without down-playing important uncertainties and ambiguities.

This difficulty was made public when Siddhartha Mukherjee, the author of The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction, published an article in the New Yorker in May 2016 intended to bring epigenetics to public attention and also announce a book he was publishing on the gene, The Gene: An Intimate History.

The article provoked quite a storm of criticism, as Mukherjee seems to have focused on one epigenetic mechanism, histone modification, at the expense of more important ones, such as transcription factors. A leading critic was, again, Jerry Coyne who wrote extensively about the article on his blog and gathered critical statements from other leading scientists such as the molecular biologist Mark Ptashne and the geneticist John Greally, amongst many others. In due course the book on which the article was based was published and a while later it was partially corrected in light of these criticisms. So that’s all good.

This episode has, however, exposed some pitfalls in popular science writing about epigenetics. As Tabitha M. Powledge said in a blog post: “The piece is a fine example of the chief science-writing challenge: How damned hard it is to explain a complicated topic without major distortion.”

I wonder whether things might have been different if Mukherjee had read some articles and opinion pieces written around 2012/13 when epigenetic hype was abundant and grand claims were being made left right and centre, but when, at the same time, criticisms of such hype were also being voiced. Razib Khan, a population geneticist, for example, said: “Epigenetics is real, and probably important, but it doesn’t imply that there’s a revolution and that everything that has come before needs to be thrown out.” Edith Heard, a leading figure in epigenetics, was quoted in an article for The Guardian as saying: “’Even our epigenetic changes are genetically driven. The code of genetics is the code. It’s the only code.’ But now with epigenetics, ‘people are hoping we can pray our way out of faulty genes’…. ‘It’s our duty as scientists to pass on the right messages. I don’t want to say epigenetics isn’t exciting … [but] there’s a gap between the fact and the fantasy. Now the facts are having to catch up.’”

This advice also applies to science writers who have to find a way of reporting on a complex, fluid and developing field of study with insight, but also, I’d say, with humility, and, of course trying to distinguish between fact and fiction.

The multiple meanings of epigenetics

The problem is that at the moment, and perhaps catalysed by this controversy, epigenetics is revealing a multiplicity of sometimes contested meanings – meanings that have been jostling around for quite a while. This prompted scientists like Joshua Lederberg and Mark Ptashne to reflect on the meanings of epigenetics and the language used to talk about epigenetics as early as 2001 and 2007 respectively; and the semantics of epigenetics has been discussed ever since.

More recently, Steven Henifkoff and John Greally have pointed out that: “The field described as ‘epigenetics’ has captured the imagination of scientists and the lay public. Advances in our understanding of chromatin and gene regulatory mechanisms have had impact on drug development, fueling excitement in the lay public about the prospects of applying this knowledge to address health issues. However, when describing these scientific advances as ‘epigenetic’, we encounter the problem that this term means different things to different people, starting within the scientific community and amplified in the popular press.”

Another recent article by Eric Nestler (which deals with issues around ‘stress’) also tries to sort through the different meanings of ‘epigenetics’, after pointing out that “the term epigenetics is used in at least three different ways, each referring to a fundamentally different mode of biological regulation, which has contributed to considerable confusion in the field.“

As early as 2010 the historian of science Evelyne Fox Keller had claimed that the meaning of epigenetics is surrounded by “a muddle” and Grant Jacobs wrote a blog post about ‘epigenetics, a confused muddle in the media’. Things don’t seem to have changed a lot since then, but the muddle is more openly discussed, which is great. Greally is quoted in a piece in Nature that deals with the Mukherjee controversy as saying: “We’re in a bit of a mess in epigenetics.” This is, of course, not necessarily a problem. Martyn Pickersgill, a specialist in the social study of biomedicine, found in his research that “scientists are hardly paralysed by uncertainty” (as uncertainty is an integral part of science).

However, as Aleksandra Stelmach and I have pointed out in an article on metaphors used in reporting on epigenetics, natural and social scientists, philosophers and, indeed, science writers have to be aware of and alert to the fact that matters are still in flux when it comes to epigenetics. This means we should not make over-hyped claims about the scientific or about the societal and political implications of epigenetics. We should also not play down existing uncertainties and ambiguities.

The ‘plasticity’ of epigenetics itself has to be acknowledged before building up promises and hopes around epigenetic plasticity or projecting fears about possible eugenic futures.

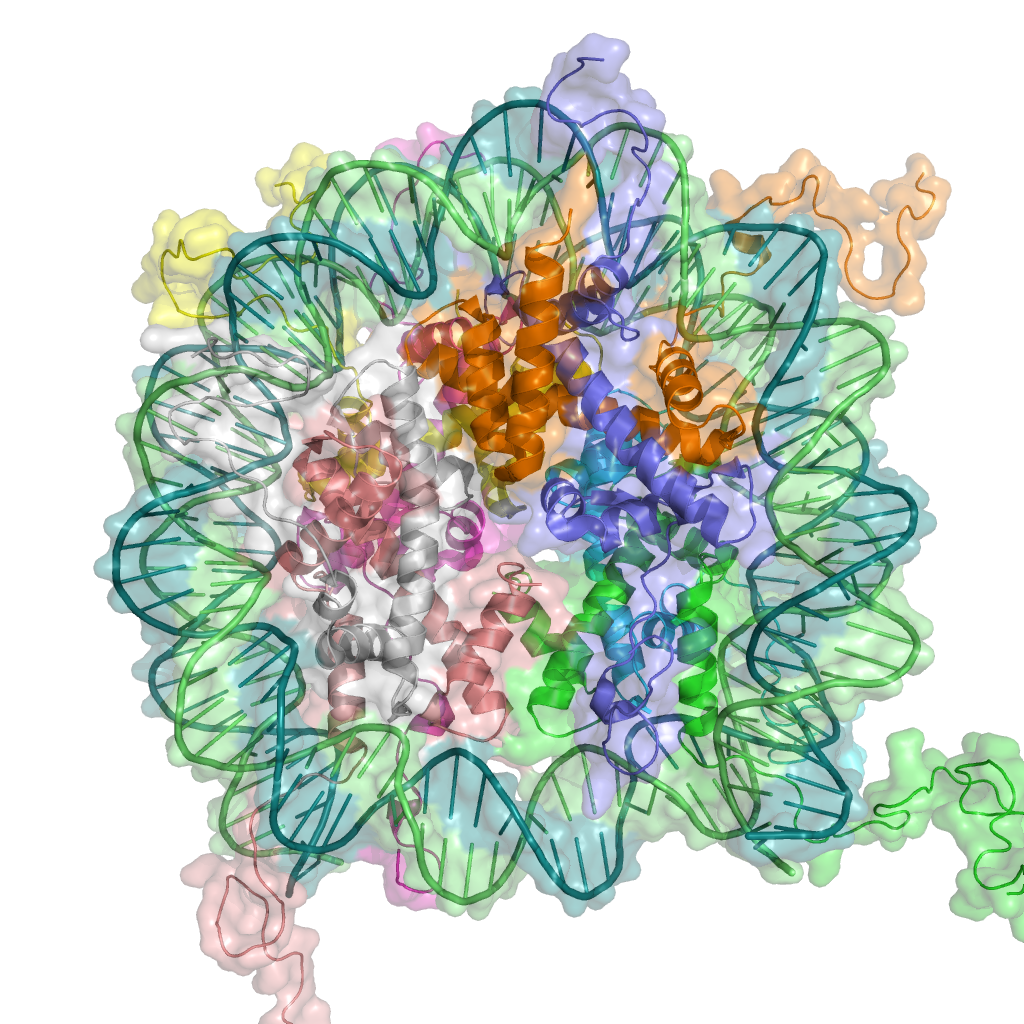

Image: Nucleosome, by Zephyris at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

PS 7 August 2016 – and something I didn’t mention and which makes things even more complicated: Einstein Epigenomics @EpgntxEinstein “The shift in use of #epigenetics from developmental to molecular biology completely screwed the definition”

This week I asked (early teenage) No3 Son what he had been doing in science at school today. He responded by explaining to me what mRNA was, how proteins are made and the epigenetic effects of 9/11

https://www.theguardian.com/science/neurophilosophy/2011/sep/09/pregnant-911-survivors-transmitted-trauma

My gob was well and truly smacked. Things have clearly moved on since my day.

My gob is well and truly smacked as well!!! This might be of interest: https://www.theguardian.com/science/occams-corner/2014/apr/25/epigenetics-beginners-guide-to-everything