June 5, 2019, by lzzeb

The Saint John River valley: memories of a submerged riverscape

A blog by Dr Stephen Dugdale

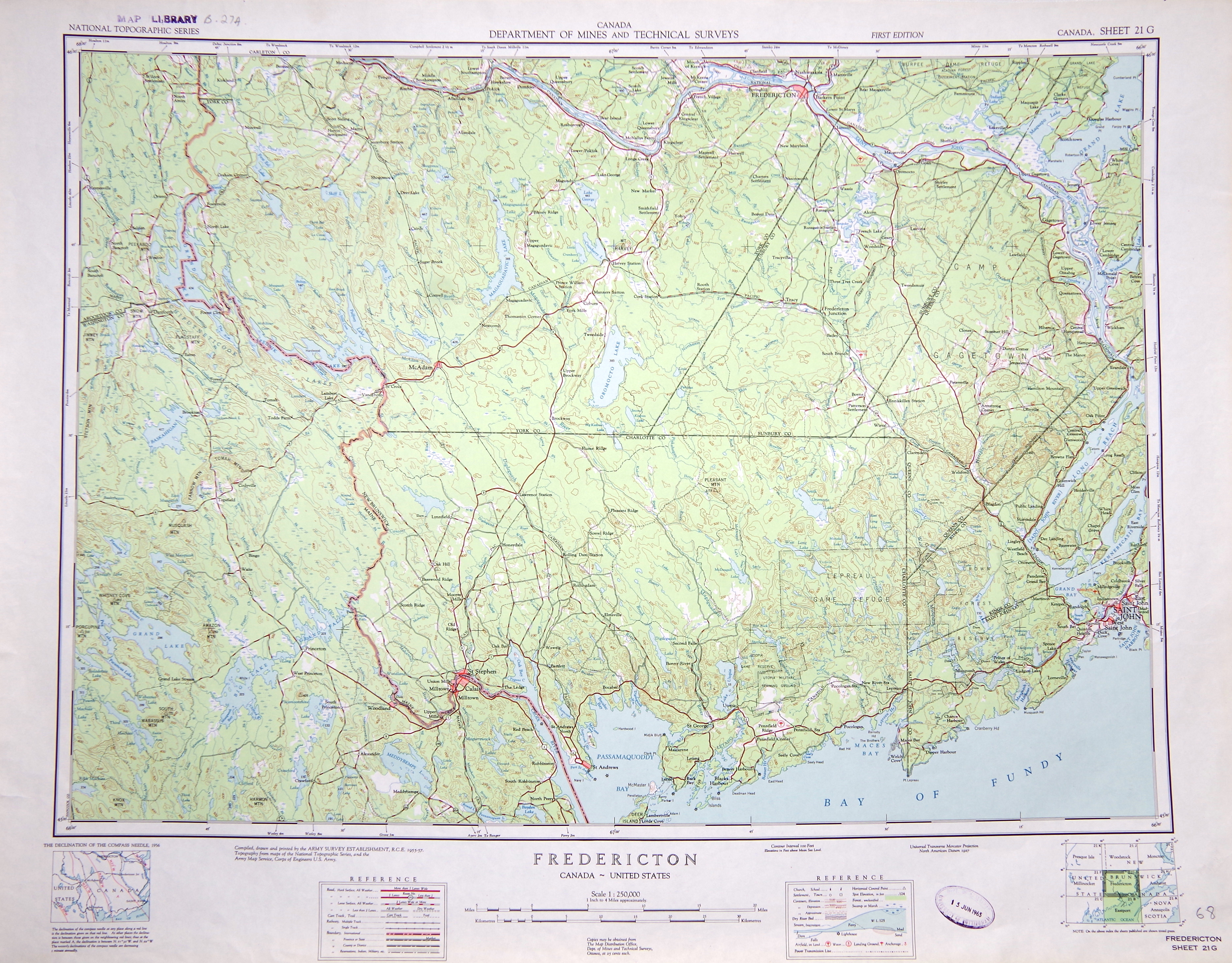

The School of Geography’s map collection contains a large number of historical maps of Canada. Two of these, sheets 21G and 21J of the National Topographic Series 1:250,000 collection (published between 1955 and 1959), are of particular interest. These maps, centred on Fredericton and Woodstock in the maritime province of New Brunswick, show the Saint John River valley prior to its flooding by the Mactaquac Dam, an immense hydroelectric power station constructed between 1965 and 1969. Shown here is sheet 21G (Fredericton), with the pre-dam Saint John River visible towards the northern edge of the map.

The impact of dams and other obstructions on river ecosystems is increasingly viewed as a global threat to both freshwater biodiversity and human water security. As a result, dam removal has become a hot topic around the world, with successful dam removal projects such as the Elwha Dam (Washington, USA) showing how rivers can quickly recover from the damage caused by impoundment. Before arriving at the University of Nottingham, I was involved in a project to assess the viability of removing the Mactaquac Dam (the Mactaquac Aquatic Ecosystem Study or MAES for short) and restoring the Saint John River to its pre-dam condition. Although ultimately, the decision was taken to leave the dam in place until the 2060s, historical maps such as sheets 21G and 21J allow us to delve into the past and understand what the riverscape looked like before flooding…and what it might possibly return to if the dam is removed in the future.

Despite my contribution to the MAES project, I had never actually seen what the area looked like prior to the dam’s construction, and therefore had little appreciation of the sheer enormity of the area that was drowned by the dam. The pre-dam maps show that in the past, the Saint John River measured approximately 400 m in width at its largest point, much smaller than the current day reservoir (rather modestly known as the ‘Mactaquac Headpond’) which varies between 2 and 5 km wide and is almost 100 km in length! Unsurprisingly, today’s Mactaquac Headpond obeys the hypsometry of the historical maps, with the shoreline of the reservoir closely following contours located substantially above the river channel in the 1950s sheets. However, what is particularly interesting is how the reservoir is determined by, but continues to alter, the stream network of the pre-dam watershed.

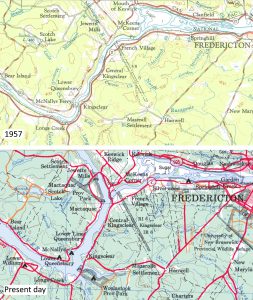

Detail of map sheet 21G from 1957 (top) alongside present day 1:250,000 map of the area (bottom). Note the presence of the Mactaquac Arm (present day) in the location of the former Mactaquac River (pre-dam, 1957), near Jewetts Mills. Also visible are several large embayments/coves located over the former confluences of minor streams/creeks (eg. Longs Creek, located towards the south of the image).

One example of this is the fork in the present-day reservoir immediately upstream of the Mactaquac Dam, shown here on a detail of the 1957 map, and on a present-day map of the area. One ‘arm’ of this fork, the Mactaquac Arm, occupies the valley of what was previously the Mactaquac River, a relatively minor water course 30-50 m in width. The dam transformed this stream (and its valley) into a gigantic embayment 500 m wide and almost 12 km long, requiring the relocation of several thousand people from the village of Jewetts Mills and surrounding farmland. Some of these residents were the descendants of loyalist soldiers from the American War of Independence, and had been gifted fertile land near the river in recognition of their service. The straight roads and tracks radiating perpendicularly from the Saint John River (visible on the map) are a relic of the patterns of landownership associated with these smallholdings. Other people displaced by the drowning of these farmsteads owed their existence to the Underground Railroad that helped freed slaves from the south to settle in the vicinity of Fredericton. Opposition to the dam’s construction was therefore understandably fierce, as it came at a large cost to the cultural heritage of the area. As a result, a range of historically-significant buildings were relocated prior to submergence, and are now preserved in the King’s Landing historical village located on the shore of the current day reservoir.

Photograph looking up the Mactaquac Arm taken from the shoreline of the Mactaquac Headpond (between Kingsclear and French Village).

Another notable contrast between the past riverscape and the new one created by the Mactaquac Dam is the transformation of small tributary mouths into ocean-like ‘coves’ far larger than the area occupied by their former confluences with the Saint John River. The mouth of the Nackawic Stream, located below the ‘D’ of ‘Department of Mines and Technical Surveys’ on map sheet 21G, is a particular example of this. Once a minor confluence marked by a small gravel delta, this river mouth is now a huge bay approximately 1.5 km across known as Culliton Cove. The creation of numerous coves along the length of the former Saint John River valley, coupled with the generation of artificial harbours from areas of high ground which were partially flooded during the reservoir’s creation, gives the Mactaquac Headpond a distinctly maritime feel in places. The daily raising and lowering of water levels by as much as 1.5 m (due to the storage and release of water for electricity generation) results in an artificial ‘tide’ which only adds to this impression. However, while gentle in appearance, this variation in water level has resulted in a flow and temperature regime that has greatly altered the ecosystem of the Saint John River.

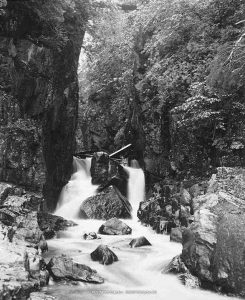

A final point of interest visible on sheet 21G is the Pokiok Stream, situated a little further upstream from the mouth of the Nackawic Stream (below and to the left/west of the ‘D’ in ‘Department of Mines and Technical Surveys’). Prior to the Mactaquac Dam, the confluence of the Pokiok Stream and the Saint John River was the location of Pokiok Falls, a waterfall and 22 m deep canyon that was a favourite spot among tourists and locals alike. Although the falls, shown here in a photograph from the early 1900s, are not marked on the historic map (its scale is too coarse for this), the change in elevation responsible for the waterfall is visible from the contour lines, giving us an idea of the shape of the Pokiok canyon prior to the construction of the dam. Now submerged beneath the Headpond, the confluence of the Pokiok Stream and Saint John River looks rather ordinary, with nothing remaining to hint at the majestic canyon and falls hidden beneath the water.

Early 1900s photo of Pokiok Falls, prior to their submergence by the Mactaquac Dam. Photo source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CN003379.jpg [public domain]

Although the once-renowned landscape of the Saint John River valley has been partially forgotten, it is kept alive through historical maps, old aerial images, and analogue photos stored in archives and map collections such as this. Time will tell whether the dam will ultimately be removed and if so, to what extent the restored riverscape will still resemble its pre-1960s state.

National Topographic Series 1:250,000 map sheet 21G (1957) showing Fredericton (New Brunswick, Canada) and environs. The pre-dam Saint John River is visible along the northern edge of the map sheet. Click to enlarge image.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply