August 6, 2019, by lzzeb

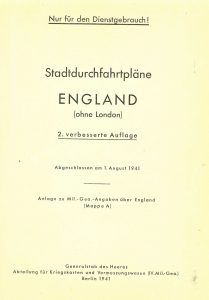

Imagining Invasion: Stadtdurchfahrtpläne England (ohne London) 2. Verbesserte Auflage, 1941

A blog by Dr Isla Forsyth

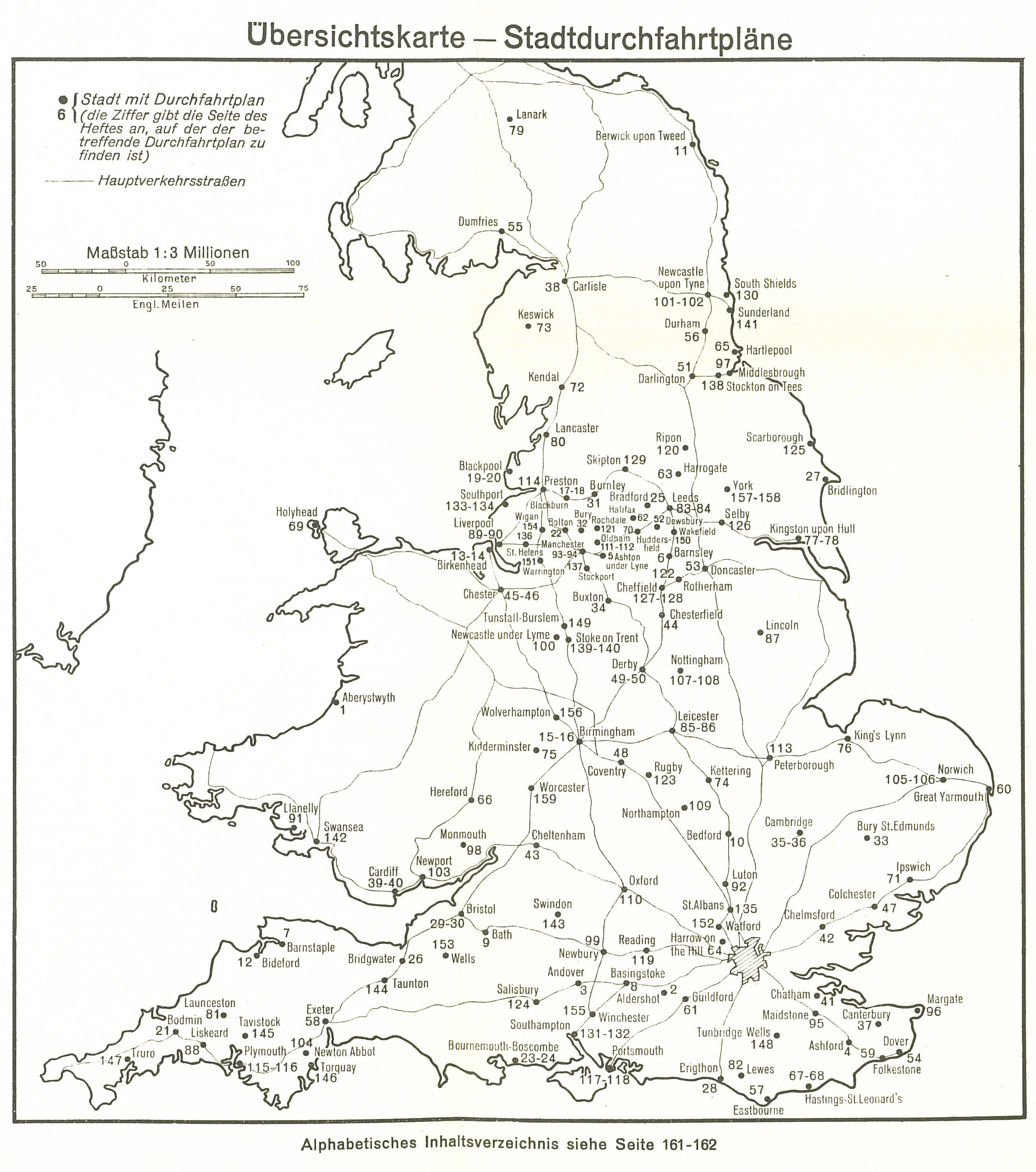

The above map is the frontispiece to a booklet produced by the German military in the Second World War, which details the local geography of British city road maps, as well as the distances and directions for and between different cities and nearby towns. These military maps were produced so that in the event of an invasion German troops would be able to navigate and mobilise with ease and efficiency across Britain. This map highlights that the military map is an object of violence as much as it is an object of imagination. It is a cartographic abstraction, producing a place and constructing a target for military violence. The military map is thus an integral component in the arsenal of war.

The School of Geography map collection at the University of Nottingham has a large collection of First and Second World War maps. This rich collection of maps charts infamous battlefields and shifting geopolitical boundaries, which over time and through conflict have been drawn and redrawn. Within these maps violent action is writ large across their contours. However, the focus of this blog is directed upon a map – or more accurately, a book of maps – that records the mundane, local and unrealised geographies of war. It is this anticipatory map and the violence it promised which makes it an especially unsettling military map.

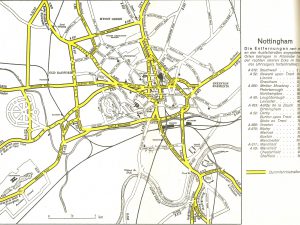

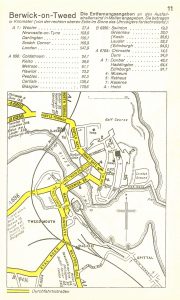

Object B109 in the map collection is a road atlas of British towns and cities from August 1941, produced by the General Staff of the German military surveying department. It is quite literally a road map to invading Britain. From Truro to Lanark and across one hundred and sixty pages, main streets and roads are charted, thick yellow lines mark the routes to be taken by German artillery, soldiers and equipment across Britain that would ensure a smooth and efficient occupation of the island. German troops armed with this booklet would on landing in Britain be able to navigate the through and between towns and cities avoiding wrong turns, bottlenecks or getting lost. The maps demonstrate clearly that a firm grasp of local geographic knowledge was of essential value for the waging of war. The importance of geography (in particular cartography) to the military had been widely appreciated by European states since the nineteenth century, and the development of distinct academic geography departments in European universities was in a large part driven by the utility of geographical knowledge to the military for imperial expansion and colonial control. Therefore, from the outbreak of the Second World War the British state recognised the significance of its local geography to the enemy and thus ensured that an important aspect of British anti-invasion preparations included the removal or defacing of signposts and milestones. The hope was that by obscuring geography the enemy would be confused, disorientated and any attempts at invasion would be successfully resisted. This book of military maps reveals that grand scale geopolitics requires an intimate awareness and appreciation of local geographical knowledge if it is ever to be effectively realised.

In first encounter this booklet compels a desire to locate familiar places and to see what roads mattered. The mind inevitably begins to imagine a counter history that is at once sensational and situated, violent and mundane. This book of maps reveals the level of detail required and undertaken for military planning, how countries were required to have an intimate familiarity with the local geography of their enemy nation states. It highlights that war is about scale, mobility and knowledge as well as strength, power and violence. It also reveals that war is about imagination as much as detailed planning, meaning that these maps are positioned ‘between dream and reality, and suspended between the future and the present’, albeit now reassuringly viewed as the past.[i] The booklet also demonstrates how ambitious and violent anticipatory geographical imaginations are exercised through prosaic materialities (such as a city street map) and situated in ordinary locales (Nottingham and Berwick-upon-Tweed to name two with which I am most closely acquainted). I traced my daily commute, from a suburb in the north of Nottingham to the campus in the southwest – the A60 south turning right on the A52, 15 minutes on a good run and a dreary 30 odd in peak traffic – this route is traced out in bright yellow ink identifying it as a planned main route in an occupation, connecting Derby, Nottingham and Sheffield. This connection and familiarity with a location on a military map is to be confronted by the lack of glory and grandeur of war and recognise its grim, and at times, unremarkable horror.

This booklet of maps was produced to be a technology of ‘anticipatory governance’. It imagines and projects hope for a particular future, it is a tool where ‘the consequences of an event are brought into the present to be acted over’; an exercise in violent creativity.[ii] These military cartographies are neither real nor imaginary, but rather a stage somewhere in between. They are monstrous and expectant, mundane and spectacular, and it is in their ability to contain and expose these tensions that make these military maps, that much more unsettling. These military cartographies capture something disturbing about how war is imagined as thrilling, terrifying, violent and horrific.

Therefore, although these maps were never used in an invasion and were destined to represent an imagined military geography, it is these very qualities of the maps, which help to make war real. Such maps can be objects which ‘bring battles back to the home front’ and evoke different relations to how we relate to war, which have the potential to constrain and control the exercising of military violence. [iii] Donna Haraway explains that when we ‘touch and are touched’ by a story, and these maps tell one such story about the geography of the Second World War, we ‘inherit’ different relations and begin to ‘live’ different ‘histories’. [iv] Object B109 in the School of Geography, University of Nottingham, is an example of unsettling cartography, as its evokes disconcerting imagination of a counter military history firmly rooted in the familiar and provokes a disturbing recognition that violent military geographies are always local, situated and familiar to those that experience them; they are not imagined, they are not thrilling.

[i] Anderson, B. Kearnes, M & Doubleday, R. (2007) Geographies of nano-technoscience, Area 39 (2) p.139.

[ii] Anderson, B. (2007) Hope for nano-technology: anticipatory knowledge and the governance of affect, Area 29 p.159

[iii] Woodward, R. (2005) From Military Geography to militarism’s geographies, Progress in Human Geography 29, p.732.

[iv] Haraway, D. (2008) When species meet University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, p.37.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply