December 4, 2020, by Brigitte Nerlich

Protein folding and science communication: Between hype and humility

During the afternoon of the 30th of November, I looked at Twitter and saw that somebody had retweeted a tweet by Tom Whipple, the Times science editor, saying that in an hour he would announce a big science story. That retweet was an hour old. I got curious and hunted around a bit in the comments etc. and found references to DeepMind, AlphaFold, protein folding, and AI.

Yes, it was that story, which, indeed has turned out big, namely that, according to DeepMind’s own press release, “a solution to a 50-year-old grand challenge in biology” has been found. The challenge or problem was that of protein folding, that is, whether it was possible to work out the 3D structure of a protein from its one-dimensional genetic sequence of amino acids. And it’s important to keep in mind that sequence (mostly) defines structure/shape and structure/shape (mostly) defines function – what a protein does, and once we know the function, we can do things…

I can’t go into the history of this advance or its super-interesting link to gaming and gamers (citizen scientists!) who laid some of the foundations for the AI to work out the problem. If you want to know a little bit more about that listen to this interview with DeepMind’s founder Demis Hassabis on BBC Radio 4 Today. There is also a longer interview with John Moult, Co-Founder and Chair of CASP, on BBC Radio 4 Inside Science, which provides more insights into how this advance came about.

Excitement

Science communicators went into almost immediate action and created ‘threads’ explaining what was going on. Threads have come a long way since I first talked about them about a year ago in a post relating to epigenetics entitled “Threads, worms and science communication”. Somebody should now write an article entitled: “A stitch in time: Threads and real-time science communication”.

The thread that struck me as one of the best and most ‘real-time’ was by Adam Rutherford (appended to or stitched to a retweet of a Guardian article announcing this development), posted at around 4.30pm that afternoon. There are many more threads about protein folding and DeepMind if somebody wants to dig them out, including one by DeepMind itself of course. And here is a small thread by the science journalist Ananyo Bhattacharya detailing some of the background to this exciting announcement. One tweet in this thread really surprised me, a quote from The Economist: “AlphaFold 2 was, for example, able to predict the structures of several of the proteins used by SARS-CoV-2 virus, including spike.” We have a right to be excited!

Caution

There were however also words of caution, some uttered in single tweets, some in threads. Here is one by science writer Philip Ball, warning about hype and asking in a way, for more responsible reporting (and I shall come back to others).

Yes, I thought: human genome project = we can read the book of life; stem cells = they are magic; synthetic biology = we can write the book of life; epigenetics = we can control our life… but in all cases things proved to be more complicated. And now it seems, we have: protein folding solved = life solved. As Philip says: “so much of the excitement draws on the obsolete idea that ‘the secret of life is written in code in the cell, and we just have to crack the code!’. This is untrue. It is badly and sometimes even dangerously untrue” (and he’ll write more about that, I am sure; and sure he did).

Hype and stale metaphors

This made me think, of course, about the mainstream media, including Tom Whipple at The Times. What were the headlines surrounding the protein folding announcement and did they differ from previous announcement of advances in genomics (and from the Twitter threads)? I had a quick look and I found some honest hype, but more disappointingly, I found a lot of stale metaphors. We just seem to be unable to celebrate an advance in science with an equal advance in (responsible) language.

Whipple’s good overview of this scientific development in The Times was headlined on 30 November: “DeepMind finds biology’s ‘holy grail’ with answer to protein problem” and on 1 December “Biology’s ‘holy grail’ will unlock new treatments to fight disease”. This was not the only holy grail I found. The Daily Star shouted: “Groundbreaking AI solves biology mystery in ‘holy grail’ for treating diseases” (30 November) and the i-independent announced: “Discovered by scientists and AI: the holy grail of biology” (1 December). Perhaps sub-editors who write headlines should be more involved in discussions around hype as well as stale metaphors? I remember when my colleague Alison Anderson wrote a media analysis in 2002 highlighting the shortcomings of the holy grail metaphor.

Other headlines contained the usual phrases we have come to expect from other genetic and genomic announcements. Of course, there is talk of a revolution, of a game changer, and of a breakthrough, but not any old breakthrough: a stunning, historic, world-changing, once in a generation breakthrough. The usual ‘science is a journey’ metaphor is exploited when journalists talk about a startling, momentous, enormous, great, gigantic leap forward, a stunning advance, of crossing a threshold, opening a door, unlocking … a mystery.

What DeepMind/Google had framed as a ‘problem’ becomes a mystery, a puzzle, a riddle. And solving it is solving life, as a Times headline proclaims: “Deepmind computer solves new puzzle: life” (1 December). The Daily Mail says: “Riddle that could cure the incurable” (30 November). What Google had framed as solving (a problem) becomes ‘cracking’, although solving is also used a lot: cracking a 50-year-old biology conundrum, problem, challenge, and of course mystery, riddle, puzzle. Cracking leads to ‘code’ but not too often and not in headlines. We find cracking the code and also, but rarely, cracking the code of life. The Deutschlandfunk says on 2 December: “crack the riddle of the so-called ‘second genetic code of life'”. Die Welt refers to the proteome (the entire set of proteins that can be expressed by a genome) as “the second code” (30 November).

Overall, most articles seem to be relatively sober accounts of this new advance, but still use, especially in headlines, tired old metaphors. A prototypical example of this style can be found in an article by Professor Bissan Al-Lazikani, head of data science at The Institute of Cancer Research for The Spectator. It is entitled: “The solving of a biological mystery”, and the first paragraph goes like this: “DNA is the blueprint that encodes the instructions to make proteins. Proteins are the building blocks and the machines that power life. And proteins make up the tissue that in turn comprise the organs and muscles that make up us. Considering how crucial proteins are to life itself, there is still so much we do not know about them. But Google’s AI firm Deepmind may just have helped us make a giant leap forward.” All the old genomic metaphors, some of them, like blueprint, now hotly disputed, come into play here.

Humility

Something like this might have prompted Lior Pachter to tweet: “I don’t mind that Google hyped this. It’s impressive work they did and there are super exciting prospects for the field. I do mind that many (computational) biologists who ought to know better are going around screaming ‘protein folding is solved!’ Have some self respect.” And not only that, they also seem to go around perpetuating old metaphors when talking about this advance.

Pachter’s reaction was mirrored in a 2 December blog post by Stephen Curry who showed in more detail that talking about the protein folding problem being ‘solved’ might be premature. The blog post itself is being updated in real-time by others bringing more knowledge to table on twitter and in comments. That’s good science communication.

Comparing some of the threads, tweets and blog posts on protein folding with mainstream media articles, one can discern a difference. The reaction on Twitter seems to have been one of excitement mixed with caution. There was less hype and more straightforward science communication, as well as awareness of some shortcomings of science communication itself. In contrast, traditional media articles seem to have been less aware of the dangers of hype and stale metaphors.

Some science communicators might enjoy reading some of the chapters in a book I edited with colleagues more than a decade ago on Communicating Biological Sciences, where practicing science writers and science media experts like Tim Radford, Stephen Strauss, Toby Murcott, Jon Turney and Fiona Fox give some advice on how to balance hype and humility, metaphors and ethics…. Something that is not easy to do, especially when something exciting happens.

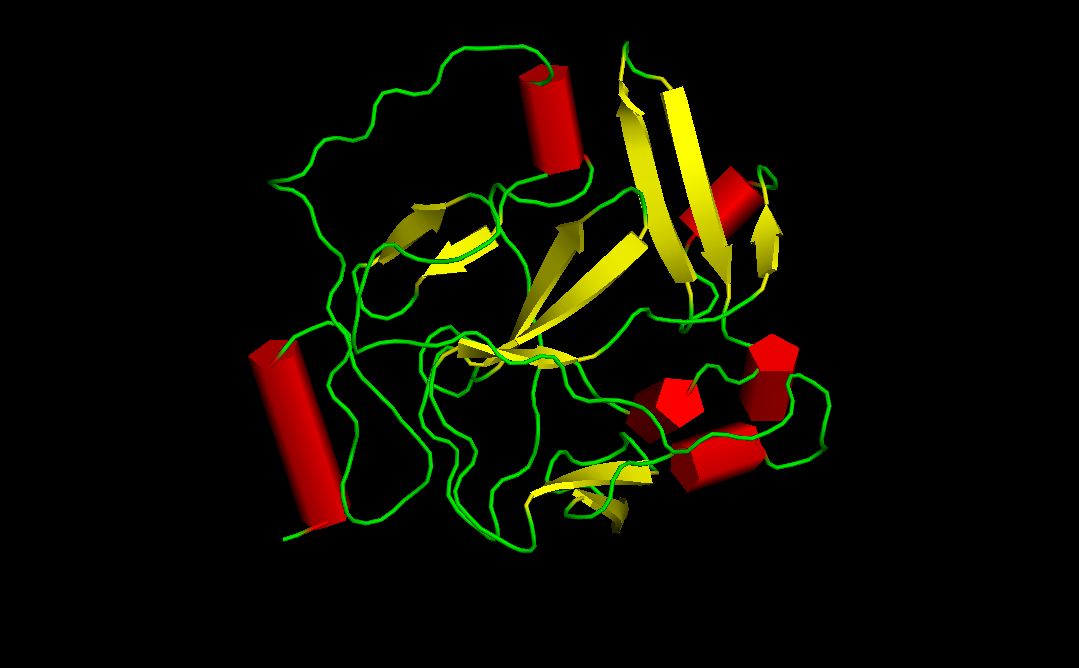

Image: Protein Folding, Wikimedia Commons

Next Post

Covid anthropologyNo comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply