January 7, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

On books, circuits and life

I have recently been trying to understand CRISPR, gene editing and genome editing. While reading about these new developments in genomics, I noticed that in the avalanche of news reports reference is only rarely made to synthetic biology (on 5 January there were 188 articles on CRISPR in Major World Newspapers on the LexisNexis news database; of these only 12 mention synthetic biology). I am not quite sure why this is, but when musing about this, I began to wonder whether the language used in the media to talk about CRISPR and gene editing doesn’t quite mash with the language used to talk about synthetic biology. I then began to look more closely into how synthetic biology and gene editing are being framed. I found some interesting similarities, but also some differences. I’ll report on these before reflecting on some problems with the master metaphors that are circulating in science and society and through which we tend to see synthetic biology and gene editing.

I have recently been trying to understand CRISPR, gene editing and genome editing. While reading about these new developments in genomics, I noticed that in the avalanche of news reports reference is only rarely made to synthetic biology (on 5 January there were 188 articles on CRISPR in Major World Newspapers on the LexisNexis news database; of these only 12 mention synthetic biology). I am not quite sure why this is, but when musing about this, I began to wonder whether the language used in the media to talk about CRISPR and gene editing doesn’t quite mash with the language used to talk about synthetic biology. I then began to look more closely into how synthetic biology and gene editing are being framed. I found some interesting similarities, but also some differences. I’ll report on these before reflecting on some problems with the master metaphors that are circulating in science and society and through which we tend to see synthetic biology and gene editing.

The book of life – take 1

Gene editing (which I’ll use here as an umbrella term for genome editing, DNA editing etc.) is rooted in an old metaphor according to which a genome is a ‘book of life’ or a ‘code of life’. For a long time, the metaphorical reader, writer and editor of that book or code was ‘nature’ or ‘evolution’. In their book on the Human Genome Project (HGP) entitled The Book of Man (1997), Bodmer and McKie talk for example about the fact that bits of DNA are “snipped out and dropped on the cutting room floor” – here the book becomes a film – “during the business of gene editing when DNA is turned into messenger RNA” (p. 81).

Some twenty or so years ago we humans gradually began to master the language in which the book of life was written and began read it ourselves, to decipher or decode it during the era of the HGP. In fact the ‘book of life’ metaphor evokes almost instantly the human genome, although every living organism has, of course, its own book of life. During and after the HGP (1990-2003 and beyond) there was much talk about us being able to edit this book of life, something that in the case of the human genome is however rather difficult.

Cutting and pasting

A decade or two before the beginning of the HGP, ‘gene editing’ had begun to be practised by scientists but without reference to the ‘book of life’ or indeed ‘gene editing’ as it’s metaphorically used today (I believe). During the era of recombinant DNA, in the 1970s, scientists began to ‘cut and paste‘ DNA using restriction enzymes. They also used bacteria as tiny factories to mass-manufacture products, a metaphor that is still being used in synthetic biology.

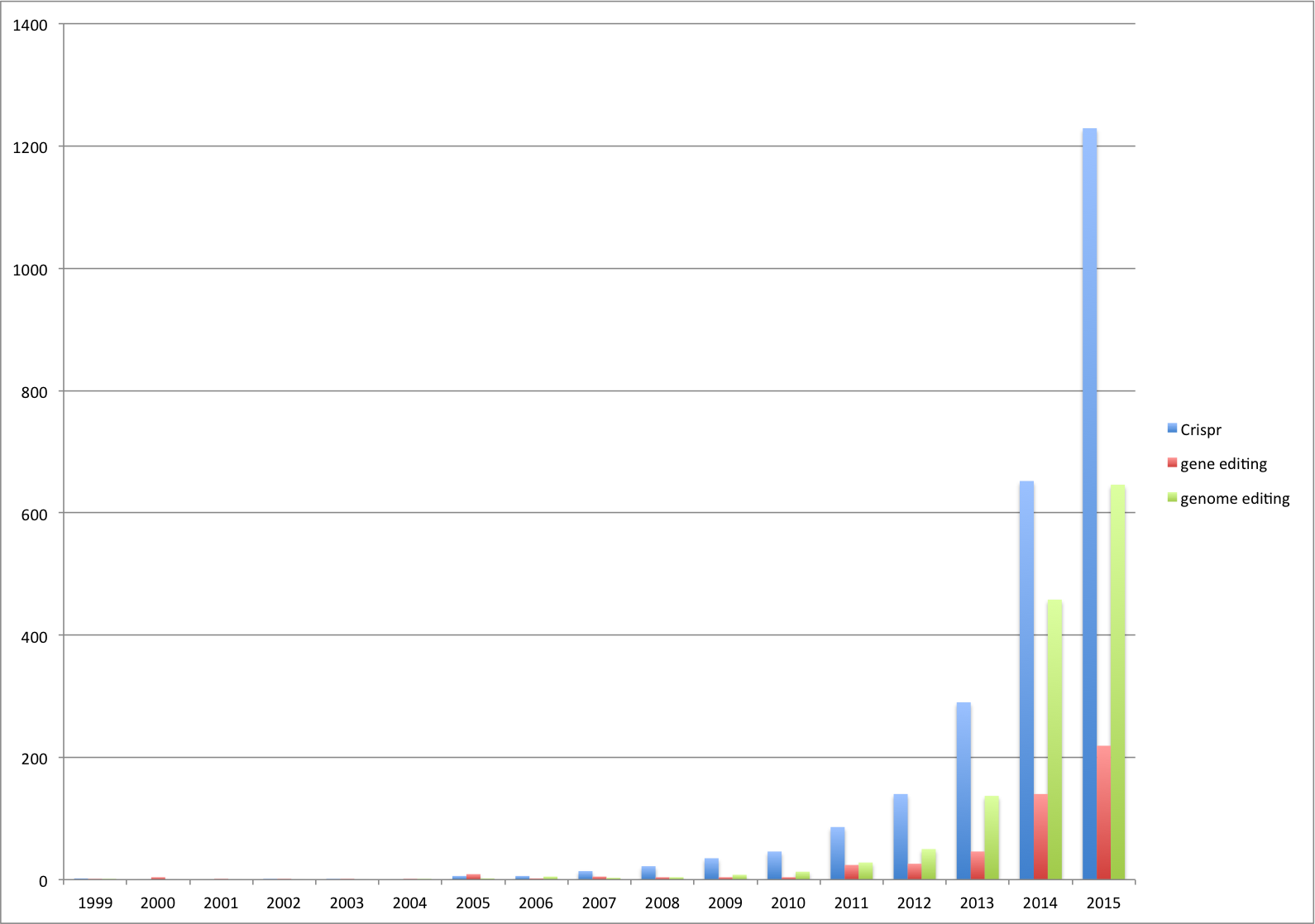

“Precise edition of a genome with controlled DNA modification at a targeted location was first performed in the 1980s by gene editing through homologous recombination.” Later on, more efficient and reliable methods or tools were developed for gene editing, such as zinc-finger nucleases, Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) nucleases, and most recently CRISPR (see also here for good overview). From the early 2000s onwards, and with a spurt in the last few years, ‘gene editing’ and ‘genome editing’ began to be used increasingly in scientific articles as metaphors/technical terms. (Figure based on numbers of articles found on the SCOPUS data base)

It is interesting to note that to describe these gene editing tools, analogies are still based on rather old-fashioned editing technologies (and their images), such as scissors and erasers, while in real-world book editing these have long been replaced by the word-processor!

The book of life – take 2

The HGP focused on reading and deciphering the human ‘book of life’. Recombinant DNA research and the gene editing practised then focused initially on bacteria. Bacteria also became the focus of an enterprise that started when the HGP ended in around 2003, namely synthetic biology. Synthetic biology was heralded as availing scientists with the power to write or re-write ‘the book of life’. This metaphor was used quite prominently around 2010 when Craig Venter built or ‘wrote’ the genome of a bacterium and almost literally left his team’s signature on it. Synthetic biologists have been writing or trying to write synthetic genomes ever since. However, this work has been framed not only by the book metaphor, but also, and even more so, by engineering metaphors.

The circuit of life

We can now cut and paste, indeed edit, genes in and out of (human, animal, plant, bacterial etc.) genomes; we can, of course, also turn or switch genes on and off. And here we enter a different metaphorical field governed by a different master metaphor to ‘the book of life’ one. We might call it the ‘circuit of life’ (this is a metaphor I invented, not one in general use!). This metaphor shifts the way we talk and think about genes and genomes away from the book (and cutting and pasting and editing paper) and towards the machine and the computer. We have all heard about the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition (iGEM), the gateway to synthetic biology. Circuit and machine metaphors (and the older factory metaphors) dominate thinking and talking about synthetic biology, which has, indeed, been defined as the “application of rigorous engineering principles to biological system design and development”.

The first inroads into synthetic biology were made when scientists created ‘synthetic genetic circuits’. And it is synthetic biology’s ambition to build or create circuits/machines/organisms that do not yet exist and to make them programmable and able to perform certain tasks. This is not what a book does, but it is linked to what a computer does and what one does with computer code.

The code of life

The metaphor of the ‘code of life’ (probably first used by Schrödinger) bridges the two master metaphors of the ‘book of life’ and the ‘circuit of life’. Although gene editing by its very name focuses our metaphorical attention on editing genes in and out of genomes, CRISPR is also said to be able to turn genes on and off. It can be used in synthetic biology to build more complex synthetic biology circuits, that is, to scale things up more easily and also to test, control and measure things more easily. CRISPR as a new gene editing tool provides scientists with precision ‘molecular scissors’ that can be better targeted and better controlled. Some people talk about this tool as “a programmable machine for DNA cutting. Compared to TALENs and zinc-finger nucleases, this was like trading in rusty scissors for a computer-controlled laser cutter”.

The book of life – take 3

And here we are circling back to the ‘book of life’ and in particular the ‘book of man’. Over and above making better and more complex ‘circuits’ for synthetic biology, CRISPR can also be used, potentially, to ‘edit’ genetic disorders in humans affected by them (in vivo, so to speak), or to create ‘gene drives’ that drive an edited gene through a whole population of disease spreading insects – all uses that go well beyond synthetic biology’s engineering ambitions. The most controversial issue relating to gene editing is that it potentially could be used to change the ‘germline’, that is, the genetic material that is passed on to the next generation – this would really change ‘the book of life’.

Artefacts and organisms

It is common practice to examine the ethical, social, legal, regulatory etc. issues posed by bio-technologies used to create or change living organisms, be they humans or bacteria. It is not so common, but, I contend, should be more common, to also inspect the linguistic ‘technologies’ we use to talk and think about them, that is, the metaphors we use, especially those that make the rewriting and redesigning of life look so easy.

We should keep in mind that books and circuits (and machines) are man-made artefacts. While such artefacts afford us with man-made metaphorical lenses through which to study life (and genes and genomes), they don’t always provide us with an altogether clear vision of our objects of study, of those (the scientists) who study them, and of the futures they will shape.

Artefact-based metaphors overexpose our power and control over genes and genomes and they underexpose the messiness and clumsy ‘architecture’ of living things. They foreground control and background complexity.

Some people have therefore tried to find new ‘master metaphors’, while others have proposed to just create awareness of the bewitching power of the sometimes “misleading” metaphors in circulation, so that scientists can get on with their work after having thrown them away. In their article “The mismeasure of machine: Synthetic biology and the trouble with engineering metaphors”, Boudry and Pigliucci (2013) argue that: “While we acknowledge that metaphorical and analogical thinking are part and parcel of the way human beings make sense of the world in some highly specialized areas of human endeavour, it may simply be the case that the object of study becomes so remote from everyday experience that analogies begin to do more harm than good.” (p. 667)

Or, to quote Wittgenstein, probably inappropriately (and I replace ‘propositions’ with ‘metaphors’): “My [metaphors] serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb up beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)” (Tractatus Logic-Philosophicus, 6.54)

PS. January 2016: an article on gene editing has been added to the online version of the Encyclopedia Britannica: http://www.britannica.com/topic/genome-editing

Image: Print-out of the human genome, Wellcome Trust

[This Making Science Public post also contributes to my social science work on the BBSRC/EPSRC funded Synthetic Biology Research Centre. You can find other posts on synthetic biology here]

[…] On books, circuits and life – Making Science Public. […]