May 8, 2015, by Brigitte Nerlich

Climate scepticism in Australia

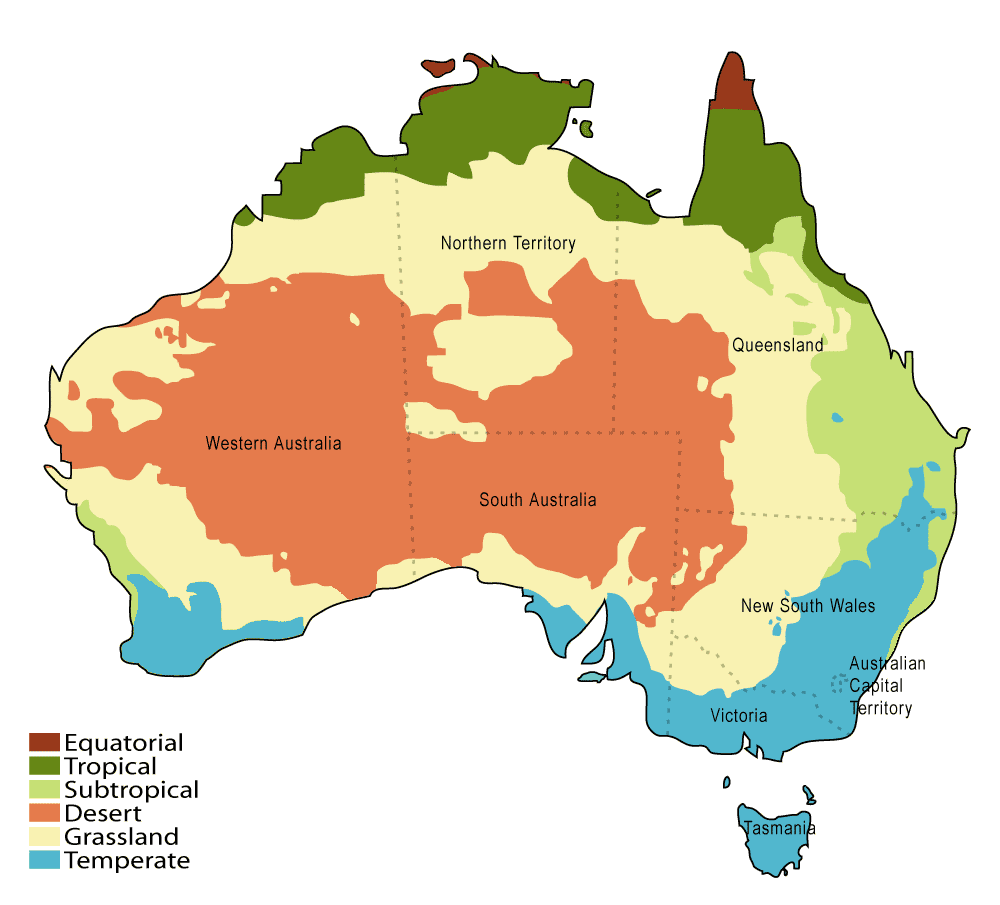

Much has been written about those who doubt various tenets of mainstream climate science. Much of this literature has focused on the United States. Far less attention has been paid to Australia, despite the fact that climate change has emerged as a central issue for Australian politics and science.

Much has been written about those who doubt various tenets of mainstream climate science. Much of this literature has focused on the United States. Far less attention has been paid to Australia, despite the fact that climate change has emerged as a central issue for Australian politics and science.

When studying the use of various labels for those who hold critical views of mainstream climate science, such as climate sceptics, climate contrarians, climate deniers, we found that one of the earliest labels used in the media was that of ‘greenhouse sceptics’, short for ‘greenhouse gas sceptics’ or ‘greenhouse effect sceptics’, and that this label was first used in Australia (see Figure 1 below). In an article for Public Understanding of Science, we, that is, Rusi Jaspal, Kitty van Vuuren and myself, explored in some detail how this label has been used in Australian print media to shape and contest climate-sceptical and mainstream climate science identities.

Greenhouse sceptics

The label ‘greenhouse sceptic’ emerged in 1989 as soon as scientists began to talk about the impact of the enhanced greenhouse effect, that is to say, the increased and harmful emission of greenhouse gases and their impact on global warming or climate change (as well as on the natural greenhouse effect). Such reflections on the relation between greenhouse gases and global warming emerged around 1988 when climate science became climate politics and began to provoke more sustained debates about climate science, global warming and the policies needed to tackle this complex global problem and its varied local impacts.

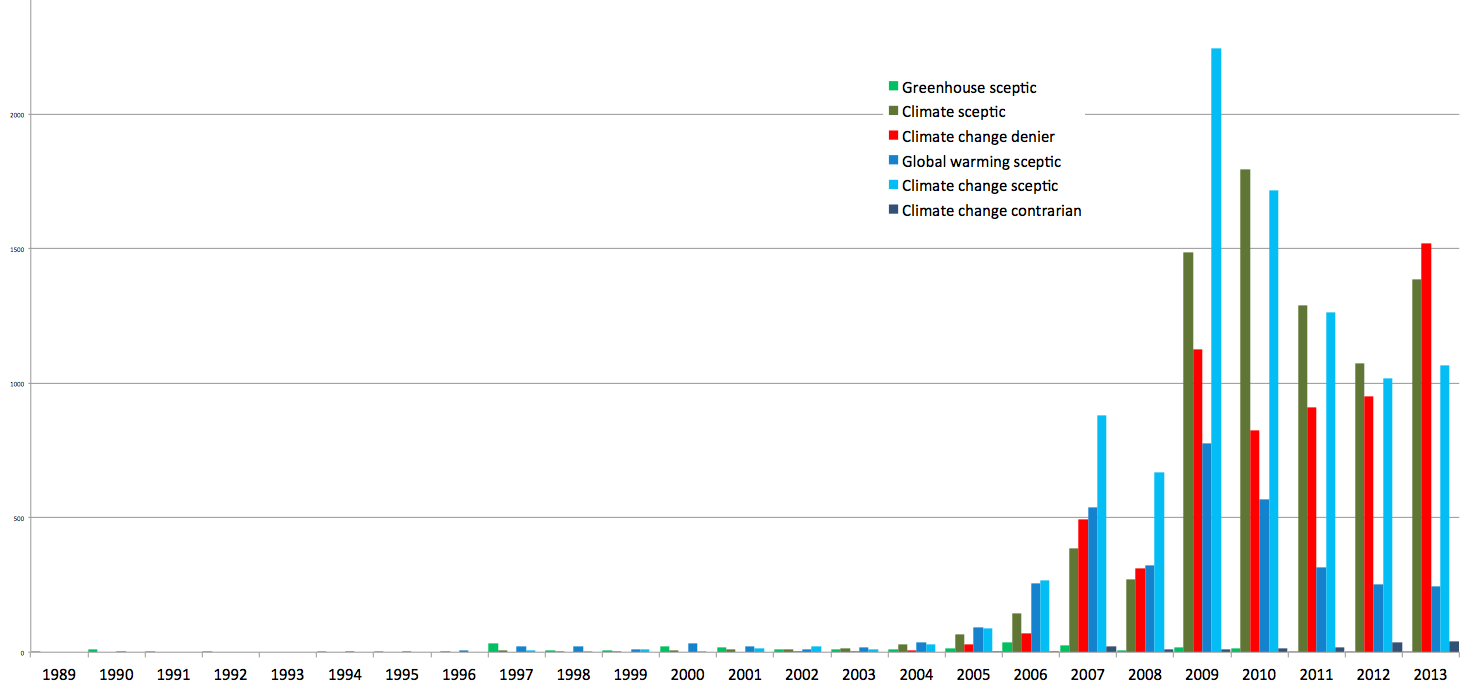

Figure 1: Rise and fall and rise of various ‘climate sceptical’ labels

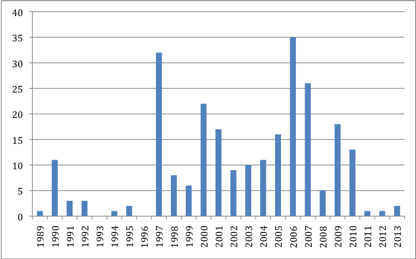

When we traced the use of the label ‘greenhouse sceptic’ in Australian print media, we found three small peaks in its use which mirror to some extent events in Australian politics: 1990, when the first Australian greenhouse gas emissions reduction proposal was submitted to Cabinet; 1997, when at Kyoto Liberal Environment Minister, Senator Robert Hill, secured a controversial concession which allowed Australia to increase its emissions by 8%; and 2006, when climate change was in the top five issues of concern to Australian voters.

Figure 2: Frequency of the label ‘greenhouse sceptic’ in All English Language News (Lexis Nexis)

Between 1990 and 2006 the label ‘greenhouse sceptic’ performed two distinct functions: (1) to label those seen to be outside the perceived consensus about climate change, or (2) to (self-)label those fighting this consensus and exposing its perceived flaws, especially in relation to uncertainty and alarmism. Through a variety of rhetorical strategies the groundwork was laid for the construction of a positive sceptic identity.

1990

In 1990, a struggle emerged between the mainstream or ‘hegemonic’ social representation of anthropogenic climate change and the competing ‘polemic’ representation of climate scepticism (‘hegemonic’ and ‘polemic’ are technical terms used in social representations theory). Scientists and sceptics began to be constructed as two distinct social groups – as individuals who perceive a bond with like-minded others in their pursuit of a common goal – with distinct, competing social representations organized primarily around truth and fallacy. A focal point for discussion was Daly’s 1989 book The Greenhouse Trap: Why the greenhouse effect will not end life on earth. Attributions of alarmism served to delegitimize climate science and to legitimize climate/greenhouse scepticism; climate scientists were delegitimized as alarmists and were equated with environmentalists, which put them at odds with dominant political interests. Religious metaphors were used to describe sceptics as brave iconclasts and ‘real scientists’ and mainstream scientists as adhering to a secretive and catastrophist cult.

1997

In 1997 greenhouse scepticism gained momentum in the Australian press through two principal paths. First, a popular book, The Heat is On: Climate Crisis, the cover up, the prescription, by the US author Ross Gelbspan, intended to delegitimize social representations of greenhouse scepticism, was employed as a stimulus for asserting sceptical representations. Climate scientists were branded ‘bullies’ and the label ‘greenhouse sceptic’ came to be used with pride, as an honorific and for self-definition. It became an empowering self-label. Through association with and mingling with US sceptics and Australian ministers at conferences organized by Australian universities, sceptics began to be framed as legitimate competitors in the climate change debate and further pushed climate scientists towards the periphery of this debate. In addition to becoming a label that differentiates ‘us’ from ‘them’, the sceptic label also acquired the potential to provide self-efficacy and self-esteem in a social, political and rhetorical context in which these very principles of identity had been challenged. Articles published during this period and, particularly, those published in response to Gelbspan’s seminal book accentuated the divide between ingroup and outgroup, and illustrated a more assertive sceptical identity.

2006

By 2006 climate change had become a particularly important topic in the Australian press, and some Australian commentators adopted the sceptic label to mount a counter-movement to mainstream science and especially Australian policies based on it. Although the label was no longer used so prominently, it still contributed to catalysing an Australian sceptical identity. The label itself contributed to the broader social representation of scepticism, which may no longer be viewed as a mere polemic representation in the Australian context but rather as having gained momentum and political importance. A sceptic identity was clearly being constructed in opposition to climate scientists and those who accept mainstream science. The sceptic label now evoked imagery of defiance and distinctiveness and was increasingly being embraced as a self-label.

2006 was Prime Minister Howard’s final year in office, amid important climate-related world events, such as the IPCC’s publication of its latest climate report, the release of the Stern report in Britain and Al Gore’s film The Inconvenient Truth, combined with Australia experiencing its worst drought on record. Climate scientists attempted to re-appropriate the ‘sceptic’ label and to re-label ‘greenhouse sceptics’ as ‘contrarians’ and ‘deniers’. This led a backlash by ‘sceptics’ against the label denier which was seen as discriminatory because of its perceived associations with holocaust deniers. This move contributed to strengthening a sceptical identity.

Labelling

On both sides of the debate, there are clear rhetorical attempts to delegitimize outgroups and to legitimize the ingroup, with a view to resisting the outgroup’s social representations and enhancing the credibility of one’s own. A principal means of doing so among climate sceptics is to anchor climate science to uncertainty, politics, fraud, and greed, while an emerging delegitimization strategy among mainstream climate scientists constitutes the anchoring of scepticism to denial.

Individuals require a sense of identity validation from others, and contestation from outgroups, in particular, can challenge the self-concept. Others’ attribution of a label with which one does not identify can induce threats to identity and widen the communicative gap between social groups, thereby accentuating intergroup conflict and polarization. Our article shows how labels and the, mostly religious, metaphors that surround them become social representations and play an important role in the climate change debate, as they separate actors into sides and determine the credibility with which their contributions to the debate on climate change ought to be viewed.

Labels can be used to construct identities and to imbue these identities with meaning and value, but they can also inhibit debate and lead to political paralysis – leaving both sides at loggerheads, rather than willing to talk. It is difficult to foresee when labels will become redundant in the climate change debate and when labelling will be replaced by cooperation between all or most societal groups, given that the label ‘climate change’ itself is also becoming contested.

Hi Briggite – I’m not sure how you managed to write this without once mentioning or apparently considering Jo Nova..

Lew and Jo were having media battles for years, in Australia, including TV appearances.

Lew/Cook put on a competing lecture, for the Watts tour of Australia – Lew named Andrew Bolt, JoNova in public lectures as deniers, freemarketeers and conspiracy theorists

Again, this is based on news data, not blogs I am afraid. So we only analysed what was in the data. Of course others can use this as background to carry out an in-depth study of the blogosphere etc. That would be very welcome indeed.

not just blogs – Lewandowsky lists all his mainstream media appearances at his blog.

there were numerous articles about Jo Nova, in the MSM as well, including tv appearances.

I didn’t got much into methods in the blog post, but when you read the methods section of the article, you’ll see how we established the body of media articles that we analysed in the end and what selection criteria we used (basically articles that contained the phrase ‘greenhouse sceptic’). I admit that this body of articles is small and excludes all sorts of articles that didn’t use that phrase. However, I still think that our analysis provides a first insight into how labels are not just used by one group to (negatively) label another group but that individuals use labels for all sorts of purposes, even to create positive images of themselves, for example. Labels are much more dynamic and used much more flexibly than people might think. There is of course an us vs them dimension in labelling. but both ‘us’ and ‘them’ play active roles in establishing that dimension and shift identities and labelling practices over time.

[…] and spread of various labels used in the climate change debate, such as for example ‘greenhouse sceptic’, I wanted to know more about the label ‘lukewarmer’ and while I can’t write its […]

[…] Greenhouse sceptics […]

[…] Climate scepticism in Australia […]