March 14, 2014, by Brigitte Nerlich

3D printing: When science and technology take us by surprise

3D printing (or ‘additive’ or ‘digital manufacturing’) has been around for a while (and we’ll see for how long further on in this post); even 4D printing has been around for a while. However, 3D printing only really came into focus for me quite recently, when I came across the metaphors ‘3D printer of life’ in the context of synthetic biology and ‘3D printing the future’ in the context of an exhibition at the Science Museum (partly funded by the University of Nottingham). The whole issue became more real when I heard the news on 12 March about a young man’s face being reconstructed with the help of 3D printing. This was for him a very real and life-changing operation.

3D printing (or ‘additive’ or ‘digital manufacturing’) has been around for a while (and we’ll see for how long further on in this post); even 4D printing has been around for a while. However, 3D printing only really came into focus for me quite recently, when I came across the metaphors ‘3D printer of life’ in the context of synthetic biology and ‘3D printing the future’ in the context of an exhibition at the Science Museum (partly funded by the University of Nottingham). The whole issue became more real when I heard the news on 12 March about a young man’s face being reconstructed with the help of 3D printing. This was for him a very real and life-changing operation.

Why hadn’t 3D printing made me sit up and notice before, I asked myself? Did it completely bypass the usual hype cycle that we see with respect to some other emerging technologies? Did 3D printing just become normal without too much hype? But more importantly, why has it seemingly evaded the radar of scholars of science, emerging technologies, innovation and ‘disruptive technologies’? (There are a few exceptions of course; and please let me know if there are more!).

In the following I want to chart the slow emergence and sudden explosion of 3D printers and printing. In a 2011 article on “The Cambrian explosion of popular 3D printing” Juan Luis Chulilla Cano points out that the “unexpected appearance of 3D printing has caught many of technology analyst by surprise”. And I should add media analysts like me too. Let’s look at some of the reasons why this might have happened.

Creeping up on us

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘3D printer’ first emerged as a word in the early 1990s. The dictionary defines this new noun as “a machine allowing a physical object to be created from a three-dimensional digital model, typically by laying down thin layers of a material in succession”. ‘3D printing’ in turn is defined as “the action or practice of creating a physical object from a three-dimensional digital model by means of a 3D printer”. The first example they provide is from 1992 and refers to ‘promises to revolutionize manufacturing’. So promises have been around for quite a while and, perhaps, for even longer than the OED thinks.

When I looked at newspaper coverage, I found two articles on 3D printing published as early as 1987 and 1988. This is perhaps not so surprising, as, according to Wikipedia, the first working 3D printer was created in 1984 by Chuck Hull of 3D Systems Corp. In 1986 Chuck Hull coined the term “stereolithography” and “patented it as a method and apparatus for making solid objects by successively ‘printing’ thin layers of an ultraviolet curable material one on top of the other. […] In 1986, Hull founded the first company to generalize and commercialize this procedure, 3D Systems Inc, which is currently based in Rock Hill, SC.”

The first article on 3D printing I found was published in The Globe and Mail (Canada) on 24 July 1987 and entitled “Laser zaps liquid plastics for fast modelling”. It reports that the “Fotoform machine, now being field-tested by a manufacturer for 3-D Systems Inc. of San Gabriel, Calif., uses ‘stereolithography’ to create three-dimensional plastic mock-ups with computer-assisted design.” A year later, on 29 March 1988, The Times (London) published an article entitled enticingly “Technology: A magic factory at their touch”.

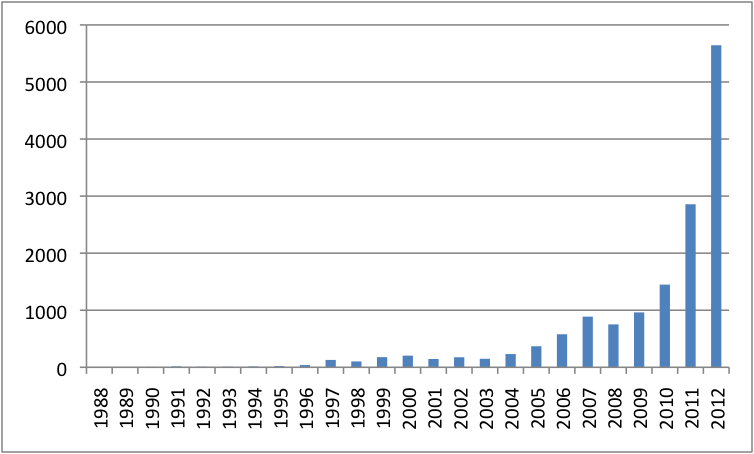

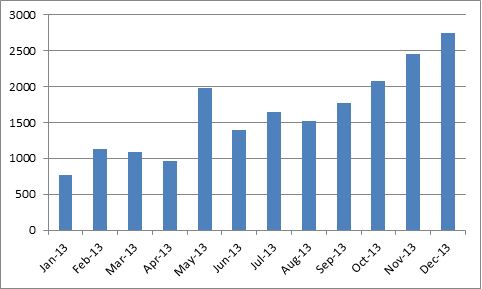

I then tracked media coverage from 1988 onwards for ‘All English Language News’ using the Lexis Nexis news database. As one can see from the following figure, it took quite a while for this ‘revolutionary’ technology to make an impact in the media. 3D printing began to attract some media attention in 2007, when I found about 1000 articles. That number jumped to about 3000 in 2011, 6000 in 2012, and over 19,000 in 2013 (see separate figure).

Figure 1: All English Language News (‘3D printer’ or ‘3D printing’, 1988-2012)

Figure 2: All English Language News (‘3D printer’ or ‘3D printing’, 2013)

A look at Google Ngram viewer shows that books started, very slowly, to be written about 3D printing and printers from the end of the 1990s onwards, with a rather steep rise after the year 2000. Google Trends, which records search patterns by Google users, confirms this trend. It records a sharp peak in May 2013, a peak that is also reflected in media coverage (figure 2). This was the time when the world’s first gun made with 3D printer technology was successfully fired in the US (BBC News, 6 May 2013).

Good or bad?

The 3D manufacture of a working gun provoked some debate about the risks and benefits of 3D printing, especially in the blogosphere and online media. Then, a few days ago, the face reconstruction event triggered this post. As I said at the beginning, I am surprised not only by how 3D printing crept up on us (as the general public), but also, it seems on science and technology analysts. There are however things stirring in the undergrowth. I found a report which I can’t pay for by Gartner (of the Gartner hype cycle), which forecasts future debates: “In Gartner Top Predictions 2014, Pete Basiliere, Gartner research vice president, and I wrote that 3D bioprinting brings opportunities and risks. By 2016, 3D printing of tissues and organs (bioprinting) will cause a global debate about regulating the technology or banning it for both human and nonhuman use. Read the full report, Gartner Top Predictions 2014: Plan for a Disruptive, but Constructive Future’”.

I am also surprised by how little ‘public’ engagement, dialogue, assessment, consultation there has been about 3D printing (but I may well have overlooked something). The only thing I could find for this post was the Science Museum exhibition I mentioned at the beginning which was part of an EPSRC effort to “generate public awareness; communicate research outcomes; encourage public engagement and dialogue; and disseminate knowledge”. While such engagement is rare and rather limited in scope, the products of 3D printing are becoming increasingly more commonplace. Since Christmas I have a 3D printed moon hanging in my lounge, made by Theo Jansen of strandbeest fame. NASA is launching a 3D printer into space to help astronauts on the space station manufacture spare parts, food etc.

From hype to normality in one big jump?

From the beginning 3D printing has been hailed as ‘magic’ and there have been increasing announcements that 3D printing will ‘change the world’, that ‘everything is becoming science fiction’, that it is ‘new black’ and that 3D printing is “a revolutionary emerging technology that could up-end the last two centuries of approaches to design and manufacturing with profound geopolitical, economic, social, demographic, environmental, and security implications.” However, for some reasons, such announcements did not trigger public debate, public outcry, public support, media articles discussing and stirring up debate or, indeed, academic or policy analysis.

I am looking forward to more public (and academic) discussions of emerging promises (3D printing of life; 3D printing of better futures; economic growth, etc.), fears (military uses, dual uses, etc.), risks, benefits, governance and responsibility related to 3D printing.

Image: Miniature human face models made through 3D Printing (Rapid Prototyping) wikimedia commons

Of possible interest: http://millenniumjournal.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/rumpala-additive-manufacturing-as-global-remanufacturing-of-politics.pdf

Many thanks for pointing me to this really interesting article!

Well, there are big, strong, civil society communities growing around 3D printing, making it possible, developing new applications, spreading the word, organizing events, training other people…. which is not a surprise, as 3D-p brings promises of freedom of fabrication. I would say that, in this particular case, technology is building bottom-up, and only after grassroots development it has become a more “official” or “renowned” fashion. So, for this case, I would say public engagement was there before the technology itself….

But maybe I’m leaving something out?

thanks!

guillermo

Guillermo, I was indeed thinking more about ‘top down’ engagement rather than the bottom up community engagement that you describe. Given that in public engagement circles of the top down sort there has been a lot of talk about ‘upstream’ engagement, I just couldn’t see it in this case. But you are right, there certainly seems to be engagement that completely bypasses such efforts.

From a personal point of view, my home life is now infused with the continuous background noise of a 3D printer! My partner (who is a mechanical engineer) has successfully built a ‘RepRap’ and I have seen a wide variety of objects (almost magically) manifest themselves in our dining room. From little glow-in-the-dark snails, to obscure engineering components, there seems to be an extraordinary range of practical and creative uses for this technology. Like you Brigitte, I also look forward to more discussions about 3D printing, and what might be the implications of it becoming a ‘normal’ and ubiquitous technology in our lives.

Oh, please bring some over when you are next in! I love snails! 3D or otherwise!

I have been into 3D printing for quite some time now. I love this newfound-hobby! I mostly use my 3D printer for making jewellery pieces, which I sell online. For those who might be interested in this stuff, I use T-Glase filament for creating the jewelleries. This machine has also helped me in many ways including spare parts replacements, toys and interior design.

3D printing is such a big adventure. If you own a 3D printer machine, you can make everything come into life in an hour or two. I’ve seen different ideas in Thingiverse and just a couple of weeks ago, I 3D printed a citrus juicer and bag holder using this filament http://www.3d2print.net/shop/3d-printer-filament/abs-filament/

With 3D printers, turning complex designs into actual products becomes easy, allowing inventors to build objects that would have been otherwise impossible. there are some pros and Cons of 3d printing too. like Easier recycling, Longer lives for products, Fewer raw materials wasted and bad is Encouraging wastefulness, Recent research indicates the 3D printing process does release gases and particles, potentially hazardous to both humans and animals

That is interesting! I hadn’t thought about that!