November 23, 2013, by Brigitte Nerlich

Responsive research: Roots and branches

My colleague Sujatha Raman recently opened up a conversation on Sciencewise about ‘responsive research’, which she defines as research responsive to public needs. The project invites people to respond to the project outline. This is what I’ll try to do in this post. I’ll first explore some semantic or conceptual issues, then try to find out what roots responsive research may have in the history of science and then map out a few existing approaches to responsive research which may overlap with Sujatha’s project. At the end I’ll pose a few questions.

Exploring the concept

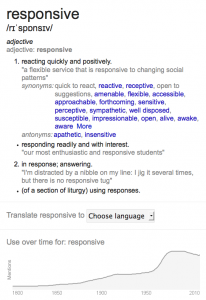

When looking the word ‘responsive’ up in the Oxford English Dictionary, it becomes clear that its earliest uses relate to rather official ways of replying to a letter: “We send yow closed wiþin þis a copie of oure lettre responsive unto þe lettres abovesaid.” (1419) For a while, responsive was used synonymously with ‘responsible’, a use that’s now archaic. Another, still current, meaning of responsive ‘is reacting quickly or keenly to something’. A search on Google reveals some other semantic aspects of ‘responsive’ that are quite interesting insofar that there are semantic links with openness and accessibility (see screenshot), which overlap with Sujatha’s focus on public participation.

Roots

When thinking about the phrase ‘responsive research’ as a whole rather than the word ‘responsive’, I began to wonder whether responsive research could have its roots in the social mission of science in general, that is of a science that should be in the public interest. This tradition of seeing science as establishing useful knowledge began with Francis Bacon and thrived in the 19th century, a century during which the phrase ‘applied science’ first became popular. (And I am expecting the following to be ripped to shreds by historians of science).

In 1620 Francis Bacon wrote in his New Organon (and I quote from this 2008 article by Rose-Mary Sargent) “I entreat men to . . . deal fairly by their own interests, and laying aside all emulations and prejudices in favour of this or that opinion, to join in consultation for the common good” because the “true ends of knowledge” are “not for pleasure of the mind, or for contention, or for superiority to others or for profit, or fame, or power, or any of these inferior things; but for the benefit and use of life” (p. 7). Within the useful knowledge tradition based in part on Bacon, “[p]ractical interests, as well as epistemic interests, are an integral part of the scientific process and thus should be part of the subject matter of philosophy of science.” Such ‘useful knowledge’ and ‘applied science‘ was visible in Davy’s miner’s lamp, in Franklin’s lightning rod, in Watt’s steam engine and much more.

John Dewey in the United States continued that tradition and defended it against an emerging discourse favouring ‘pure science’ over applied science. For him, useful knowledge is not “identical with ‘commercialized’ use”, which represented an “appalling incident” of history that had been “disastrous both to science and to human life” (p. 11). In ‘The public and its problems’, Dewey pointed out that the “glorification of ‘pure’ science” represents a “shirking of responsibility” (p. 12). By that he means that all science has social consequences, good ones and bad ones, and for these both scientists and lay people have to assume responsibility.

So responsive research can perhaps be linked to the useful knowledge tradition and certain conceptualisations of applied science and scientific and social responsibility. (There is, I think, no really good history of applied science yet, is there?)**

Branches

Let’s now jump to modern times and see whether there have been attempts at doing ‘responsive science’ that could link up with or support Sujatha’s project. When googling ‘responsive research’, the famous search engine offers phrases like ‘culturally responsive research’ or ‘gender responsive research’ or ‘community responsive research’. This is interesting, as it hints at the fact that responsive research must decide to whom it is responsive and for whom it feels responsible. Many more search hits point to the ‘responsive research’ mode that is part of the UK’s research funding landscape.*

Digging a bit deeper one finds a few, but not very many, interesting articles and activities called ‘responsive research’. One article deals with ‘responsive research’ directly, with relation to the inclusion of patients as active research partners in health research. One video provides an overview of an engaged scholarship programme in Berkeley which tries to reground academic work in the work and life of people and communities, and frames this as responsive research.

Moving away a bit from my search term of ‘responsive research’ to ‘responsive science’, there is a Hinxon Forum for Responsive Science and Engineering, but ‘responsive’ is not defined.

Other branches of responsive research, but without the name, can be found within research based on horizon scanning or foresight activities, in the grand challenges programmes of research supported by UK research funders, as well as within anticipatory governance approaches which, increasingly, want to listen to the ‘small voices of folks’ in managing research coming downstream. Most obviously responsive research overlaps with ‘responsible research’ and the emerging ‘responsible research and innovation‘ agenda. So responsive research can be big and grand but also responsive to the small voices of individuals engaging with or living with emerging technologies, which again, can be big and small, glamorous or mundane.

Questions

Some of the most important aspects of responsive research seem to be related to the speed of the response, the responsiveness to social and public needs and the responsibilities entailed by doing research that changes people’s lives. How responsive, in the sense of fast, do people want this research to be? How fast, urgent, immediate can the response be and who decides – the researchers, the public or publics, the government(s)? To whom does the research respond in terms of taking account of needs and wants: governments, local communities, global communities, small voices, big voices, and so on, and again, who decides? Who sets the agenda? Who decides priorities? And who is responsible to whom in this type of research? Who benefits? For whom is it ‘useful’? And of course where does this leave what one may call non-responsive research or what Flexner called in 1939 ‘useless knowledge‘?

While thinking about these matters, I stumbled across an article that showed yet again that “[s]ometimes the greatest scientific discoveries come from research that seems simplistic, esoteric or flat-out bizarre.” Big social benefits may come from un-responsive research. And finally, responsive research aims to produce research that ‘publics’ value, as pointed out in the overview on Sciencewise. However, quite often ‘publics’ value research (and its outcomes) which they have probably never heard or thought about before they encountered it.

Added 27 November, 2013: Just discovered this article on ‘pragmatic science‘ which seems quite relevant! As well as a special issue of ISIS on the history of applied science

Added 27 March, 2014: Great tweet referencing Millikan’s 1929 letter to Linus Pauling (I think) (HT @trueanomalies) on basic research vs useful applications

* Added 31 May, 2014: I didn’t explore the concept of responsive mode research when I wrote the blog post, but perhaps I should have. It should be quite clear however that responsive mode research is mainly what one may call ‘blue sky research’ (in a broad sense) (but of course it doesn’t have to be), whereas what the research councils call ‘targeted research’ is more akin to Sujatha’s ‘responsive research’.

** Such a history is now emerging; see article by Robert Bud on applied science and article by Désirée Schauz on basic science

Image: Chicago Fire Truck Wikimedia commons

[…] but we have to keep our ‘crampons’ ready (especially if we want to engage in ‘responsive research‘ and ‘responsible research and […]