06/08/2013, by CLAS

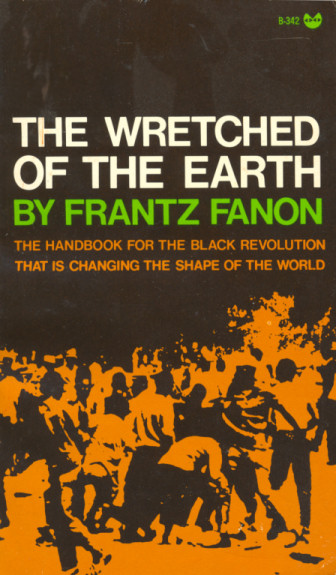

The Mysterious Constance Farrington

When people talk about translations, they usually do one of two things: either, they treat the translation as if it wasn’t a translation, talking about it as if it were a carbon copy of the original, or else they criticise the translation, bemoaning what is ‘lost’. This has certainly been the case for Constance Farrington’s translation of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (Les Damnés de la terre), a book which deals with the decolonization of Algeria and which had a huge impact on revolutionary movements around the world. ‘Every brother on a rooftop can quote Fanon’, the Black Panther leader Eldrige Cleaver is reported as saying – but of course what the brothers were quoting was not Fanon, but Farrington’s translation of Fanon: the carbon copy approach. Meanwhile scholars who have studied the translation have criticised, amongst other things, the ‘loss’ of Fanon’s voice, the occasional culturally inappropriate word-choice, the disappearance of the philosophical framework that underpins the original text: the critical approach. But there is a third approach, one which neither ignores the fact of translation nor highlights it only to criticise the translator’s choices. Instead, it looks to discover more about the circumstances in which a translation was produced, transforming the translator from a name to a person – a person who moved in particular circles, who consciously or subconsciously had their own particular agenda, or whose preferences may have been overridden by those of the publisher or other influential individuals. The translation thus becomes a small but very powerful window into the past. This historical approach might involve visits to archives, frustrating and fruitless enquiries, much Googling, many dead-ends – and occasionally, just occasionally, it strikes gold.

For months, if not the better part of a year, I’ve been trying, off and on, to find out more about the translator of Fanon’s extremely influential book, but have been drawing blank after blank. Constance Farrington, it seemed, did not translate or publish anything else, she was not connected to a university, her name did not come up in any of the available archives – in short, nothing was known about her except a much-repeated but unverified ‘fact’ that she was a member of the British Communist Party. This summer, with a little more time on my hands, I tried a new approach, taking this one ‘fact’ and trying to trace it to its source. In the tracing, I found out the piece of information that was to provide the key: Constance’s ex-husband, Brian Farrington, was still alive, and was linked with Aberdeen University. I wrote to him, then struck gold again, discovering that he’d recently written a memoir, the wonderfully titled A Rich Soup with Additional Material. I ordered it, and waited. Distracted by the kids and my younger son’s repeated efforts to ‘touch bumblebee’ in the lavender outside our front door, I didn’t notice the package in our letter box until Sunday afternoon. With the bumble-bee toucher safely down for a nap, I opened the memoir and leafed through it, excited to glimpse Constance’s name on several pages, and thrilled to see several photos of her, one from around the time of the translation. The name had a face, at last. I raced to the index, sure I would see an entry under ‘Fanon’ or ‘translation’ or ‘The Wretched’: nothing. I was a little disappointed, but carried on my reading that evening, gradually adding to the face a picture of a fiercely intelligent, talented young woman, winner of a double-first in history from Trinity College Dublin, chairman (in those days) of the theatre group, the Players. There was marriage, the move to Paris, and personal tragedy; there were intriguing stories of spotting Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in a café, and of unwittingly helping pro-FLN supporters escape from prison by providing them with nylon stockings, all of which provided valuable insight into the kinds of circles in which Constance was moving, the currents and views that would have formed an important backdrop to her engagement with Fanon’s book. And then on page 196, I struck gold for the third time, learning that in the early 60s Constance ‘became friendly with an influential, though very elderly, French political personality called Charles-André Julien. […] She gave him English lessons – he called her ma maîtresse anglaise (my English mistress) – and he got her the job of translating into English a book that was very important at the time: Frantz Fanon’s Les Damnés de la Terre, with Introduction by Sartre.’ Suddenly the half-century-long juxtaposition of Fanon’s name with Farrington’s (hers was the only translation until 2004) had a link and a story behind it, and one that made perfect sense: Julien was a prominent left-wing historian, intellectual and journalist who was strongly in favour of Algerian independence and who would have had important connections with the French publishers involved in producing Fanon’s book (François Maspero and Présence Africaine). What could have been more natural than for him to suggest his English teacher and fellow historian, whose keen intelligence and broad political leanings he had undoubtedly come to recognise and respect, as the right translator for Fanon’s controversial text?

There are of course many more details to be filled in, and many of them may truly have been lost to time, but I’m thrilled – and grateful to Brian Farrington – to have at last moved some way towards the name becoming a person, and towards a richer understanding of Constance Farrington’s version of Fanon’s text.

Kathryn Batchelor, Department of French and Francophone Studies

Photo (c) Gary Stevens

Gave her name a google seeing her credited on my copy, funny seeing as how I’ve never done so before for any other translated book, but this was lovely to read. Slightly disconcerting that I will now have to learn French to hear Fanon’s voice, but eh, cum si cum sa.