August 3, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

Pericles (Yohangza) @ Seoul Arts Centre

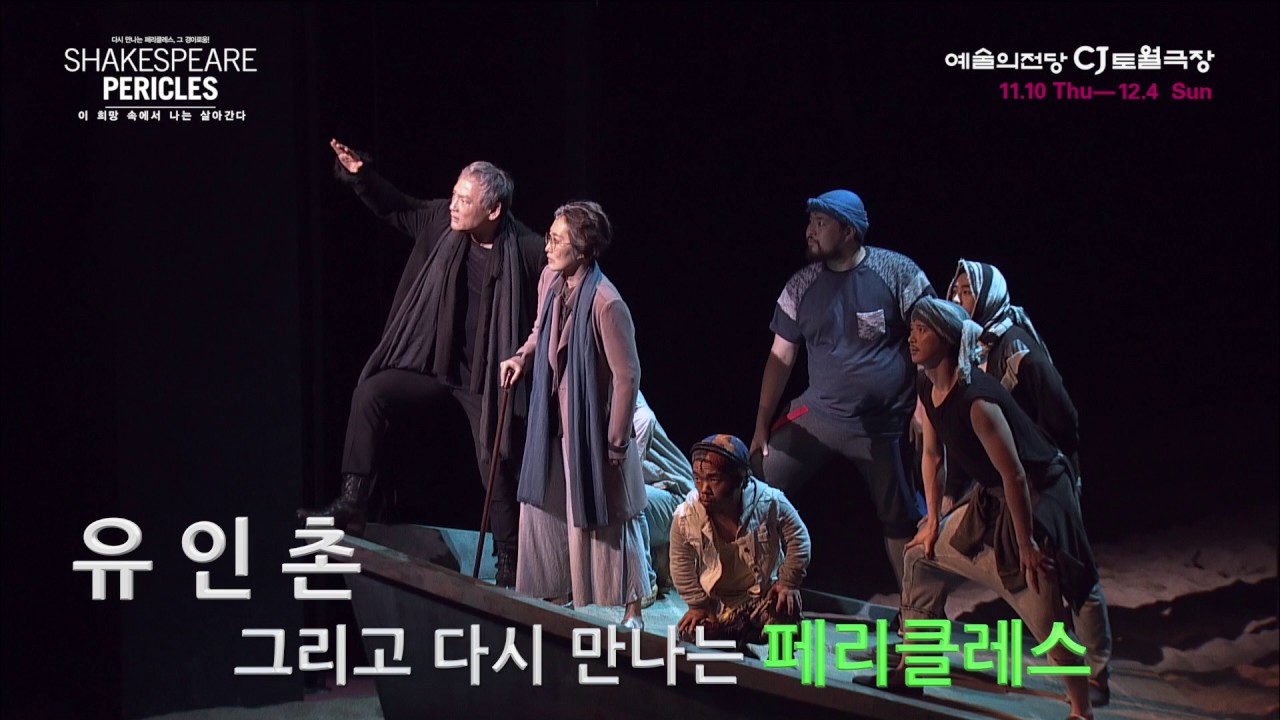

The sands of time have already covered up much of history. On Lim Il-jin’s enormous, deep stage, sand expands as far as the eye can see, into the dark recesses. The faded magnificence of the ages emerges from the sand: the colossal head of a statue of Diana, lying on its side; a chandelier near a grand piano; a double bass case; a half-submerged wooden dinghy. The characters that pass across the stage in Yohangza’s 2016 Pericles (the fantastic film of which has been made available to World Shakespeare Congress delegates) are telling a story about an age that is only partially remembered, a story for whose simplicity Gower (You In-chon) apologises. But this also allows director Yang Jung-ung to embrace the play’s storytelling qualities overtly, creating a thrillingly physical Pericles whose iconic characters emerge from and disappear back into the sands, flourishing for brief moments before leaving each other, and the audience, with only memories.

The production is a triumph of design, and beautifully captured by multiple roving cameras that take advantage of the enormous stage to capture the production from multiple angles, as if filmed in a studio rather than before a live audience. The stage is a permanent fixture, supplemented by moving platforms and bits of additional scenery, and lighting shifts direct the actors to different areas of the stage as the action shifts between different Mediterranean locations. Location and action are more importantly, however, generated by the bodies of the actors themselves, who frequently adopt a choric function to represent the transient movements of humans within this cavernous set of fixed locations.

Pericles himself is the main unifying feature of the production, but Pericles himself is fragmented. For the first two hours, Pericles is performed by two actors, one (understudy Kim Do-wan) embodying Pericles while the other (Nam Yun-ho, the usual performer of the role), sat by the piano, provides the voice. The dissociation of voice and body in the recorded performance is not part of the production’s design but a consequence of understudying; however, it works to make Pericles a figure of projection and wish-fulfilment, the silent body an object of repeated desire, fear, salvation or terror. Following his rescue of the people of Tarsus, Pericles stands in for his own statue as the grateful people gather around it/him, and this is the quality that the young Pericles carries throughout, almost too good to be true. However, Pericles’ voice (it should be noted, the ‘voice’ is always visible, and the camera director frequently showcases his performance) showcases the anxieties that drive the beautiful young man. The confidence and stability he exhibits in encountering other peoples is placed in contrast with the unsettled thoughts that prompt his constant flights. And then, for the final third of the production, Gower himself steps into the role, combining narration with the protagonist’s own thoughts, adding a further level of meta-commentary to Pericles’ experiences.

Antioch sets the tone for the production, with this debauched kingdom becoming a wrestling match. Antiochus himself (Kim Jin-gon) wears a wrestling belt over his bare chest, and his daughter (Jang Ji-ah) sashays around the competitors like a ring girl. Here, in order to even win the right to answer the riddle (the dissociation of Pericles’ diplomatic body and terrified voice works especially well here), Pericles has to overcome several opponents in an elaborate full-scale pro-wrestling bout, establishing the integration of physical prowess and mental acuity that will characterise his trials in the play’s first half.

Tarsus is in a much sorrier state, introduced by a gruesome image of a man gnawing at his own arm before dying and being set on by a number of other citizens who have turned to cannibalism. Cleon (Jang Hyeon-suk) and Dioynza (Jang Ji-ah again) are in desperate straits, as a vulture (Kim Bum-jin) caws ravenously over their subjects. The Tarsus scenes are some of the most effective in encapsulating the production’s larger sense of the ravages of time. A brief dance sequence evokes a time when Tarsus was prosperous, the whole ensemble’s pop stylings describing a happier time, before Dionyza screams at Cleon to stop dragging up the past. In prosperity, though, they return to debauchery. The people of Tarsus are initially grateful to Pericles for rescuing them (the imagery of refugees and aid is evoked in the identikit food cases brought on by his men), but Dionyza is embittered by their reliance. After Marina’s ‘murder’, a drunken Dionyza fights with a distraught Cleon, she wielding her wine bottle like a weapon and wrestling with him in their paddling pool, all while inveighing against the saintly Marina and the poor light she had cast them in. Dionyza’s repeated attempts to bury the past – both glories and misdeeds – seem most thematically linked to the production’s larger imagery of hidden histories.

Tyre itself is rarely seen, but acts as a stable centre. Helicanus (Kim Eun-hee), a woman, calms her people with dignity from aloft locations, either on Diana’s head or from the boat. In some ways, Tyre becomes the civilised centre that Pericles is continually fleeing from. Pericles’ own instability is best evoked by the storm scenes, when the moon that is regularly projected onto the backdrop (Diana’s symbol, of course) becomes clouded over. Kim Do-wan’s entirely physical performance is great for these storm scenes. He’s stripped to his underpants before Pentapolis and flips, turns and wheels as he’s caught in the waves before being caught in a net. In the later storm scene, Thaisa (Lee Haw-jung) and Pericles sit on a table being moved by mariners in sou’westers, and this time it is Thaisa’s turn to be pushed into the water, where she dances in a blue spotlight, moving through the waves as Pericles mourns her.

Yang Jung-ung uses the two scenes of rescue to develop different kinds of voice within the play. The fisherman of Pentapolis are a comic bunch who gossip about their king before their boss tells them ‘No politics while working!’ In Ephesus, meanwhile, the comic-philosopher Cerimon (Jun Joong-yong) – first seen using a blackboard to give an ethics lecture to the theatre audience – leads a troop of acolytes who find Thaisa’s body in the double bass case, though the acolytes initially struggle to open it as they’re pulling at the hinge rather than the clasp. The groups of comic men allow for displays of innate nobility by contrast, first as Pericles casually whups the fishermen’s asses when they try to condescend to him, and later as Cerimon benignly controls his followers. In these scenes, more of the fairytale qualities of the play emerge, as the noble person who is rescued takes stock of their new situation and their comic discoverers are quietened by the realisation of their nobility.

Pentapolis proper takes the form of a tacky game show, with competitors drawn from around the world. The battles that Pericles and his rivals are made to undergo are generally funny, including a ‘swim’ across the dry sand and a confrontation with a heavy-set Cyclops who sends all of the soldiers flying every time he stamps on the ground. This is one of the slighter parts of the production, but sets up the stakes for the sober ending to the first half – first as Thaisa dies and is pushed out to sea, and then in the coda as, in a storm, Pericles delivers the infant Marina to the pregnant Dionyza, and Pericles and Thaisa wander the stage, calling out in grief for the other, before Gower tells the audience that only time can heal this.

The second half is dominated by Marina (Jung Sung-min), who sings beautifully and whose singing gives the second half its unity. Marina is repeatedly assaulted by men who then attempt to rescue her. In the first case of this, in Tarsus, Leonine (Kim Do-wan) is commissioned to murder her. He comes up behind Marina as she stands on the submerged boat, and cuts her hands when she grabs his knife in self-defence. He’s appalled by the sight of her blood and wraps her hands up – but then she falls into the sea. In a prolonged but important sequence, Leonine swims to her rescue (there’s some wonderful and witty mime here), before then defending her from the suddenly arrived pirates, who – in a surprising twist – kill Leonine as he battles to protect her.

In Mytilene, the production sets up more commentary about class difference as the brothel keepers (all played by male actors, though Kim Dae-jin’s lipstick-wearing Bawd appears to be gender-fluid) debate their profession while lording it over Boult, a little person (Kim Bum-jin again). The brothel scenes first set up the mercantile rule of this environment, with Boult bringing Marina to the brothel in a procession that evokes that of a funeral and negotiating at length with the pirates for her purchase. The Bawd and Boult take their time to ‘educate’ Marina in what is expected of her, including how to ‘pretend’ that she’s being forced. But this economic arrangement is undermined by Marina’s explicit defiance. In one effective sequence, two punters at the brothel desperately try to sustain their own erections (shown by the two men putting their arm or leg between the other’s legs) and fail as Marina stands on Diana’s head and sings her holy song.

The disruption that Marina offers to a sex-based economy is nicely realised here, with a political spin. Marina thanks the punters for coming to the brothel, extols the virtues of family, and wishes that they will never return again. Then, when confronted with Lysimachus (Han Yun-choon), who arrives with all the confidence of a ruler to be massaged and preened by the fawning brothel owners, she advances the cause of victims of sex-trafficking directly. Humming and miming, she leads Lysimachus through the stages of trafficking and asks for his help. And then when even Boult tries to sleep with her to punish her for turning Lysimachus against them, she wins him over and Boult helps her to safety. The production takes the optimistic qualities of the play – that virtue will win out – and turns them into a more deliberate form of activism.

This sets the tone for the final sequence of the play, the moving reunion between Pericles and Marina. From here, the production eschews its more offbeat elements and commits to a more sombre, elegiac, and moving mode. The older Pericles is slumped, covered in his boat, unresponsive; he slowly emerges from himself in response to Marina’s story, and their reunion – and the subsequent reunion with Thaisa too – have a strong emotional pay-off, leading to the reunited family (and Lysimachus) concluding the production by putting their arms around one another and leaving together. The production finds hope in the idea of family and the rediscovery of love. But as its characters leave the sandy stage, it also calls to mind the transience of these ideas and rediscoveries, and the ease with which histories are forgotten or buried.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply