August 1, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

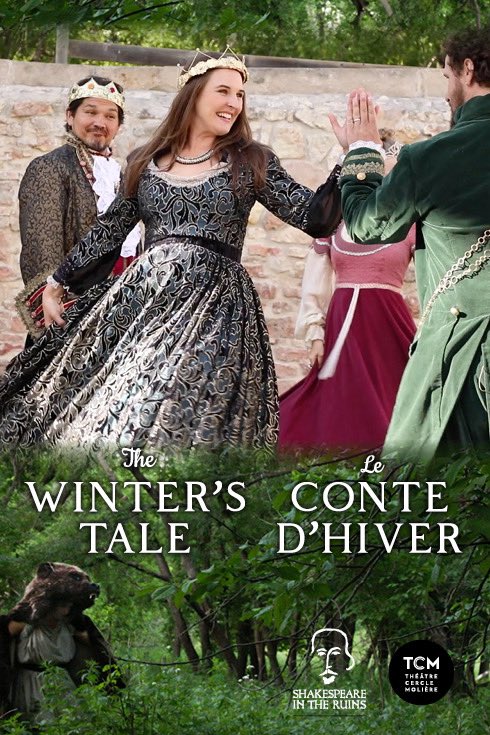

The Winter’s Tale/Le Conte d’Hiver (Shakespeare in the Ruins) @ online

Winnipeg’s Shakespeare in the Ruins has been producing Shakespeare in the picturesque Trappist Monastery Ruins since the early 1990s. While so many outdoor-based theatre companies around the world have been among the first to return to in-person performances during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, artistic director Rodrigo Beilfuss has been more ambitious, spearheading the company’s first screen production. Filmed over the course of a week, and without a live audience, directors Michelle Boulet and Sarah Constible have created a fascinating hybrid performance: a high quality film that also captures something of the excitement of promenade performance and shows off the stunning surroundings that are part of Shakespeare in the Ruins’ USP.

The Winter’s Tale is well-suited to outdoor production, and the freedom to shift from a single outdoor stage works in the film’s favour. Sicilia is based in the ruins of the old monastery, and the camera tracks through the dilapidated grandeur as if tracking the crumbling edifice of Leontes’ own mind. The setting works symbolically as well as representationally: a claustrophobic high-walled room creates an intense point of confrontation during Hermione’s arrest; an open courtyard space with parapets provides ample opportunity for the paranoid observations of 1.2; and Leontes’ self-contained throne is positioned among some of the shallowest ruins, contrasting his own isolation with the disappearance of the walls that mark his power.

When the action moves to Bohemia, though, the monastery disappears from sight, and instead the brooks, fields and woods of the surrounding country park evoke rural, rustic Bohemia. The locals dance in the fields; Autolycus (Daniel Péloquin-Hopfner) emerges from the trees; and Antigonus (Tom Keenan) is able to hide baby Perdita in convincing scrub next to a stream. The roaming camera also works to great effect here, as Autolycus adopts the privilege of direct address to the camera and beckons the camera along with him to his hideaways, from which he can observe his gulls.

The production further distinguishes the two worlds through language, embracing its Canadian identity through bilingualism. Sicilia is an English-speaking country while Bohemia speaks French, and this simple decision sets up a radical and distinctive interpretive shift in the play. Where Shakespeare emphasises the alignment between Leontes and Polixenes, here Leontes (Gabriel Daniels) is ostracised in his own country by being a linguistic outsider. Polixène (Simon Miron) speaks English happily to Leontes, but Leontes is unable to convince him to stay. Instead it’s left to Hermione to speak to Polixène in French to persuade him to stay. As the two converse in a language that Leontes seemingly cannot understand, Leontes stands awkwardly, foolishly, and begins reacting against the private discourse that his wife and his friend share.

By sidelining Leontes linguistically from the start, the production centres Leontes’ anxiety about control. It is telling that, following the gap of time, Florizel (Omar Samuels) and Perdita (Kristian Cahatol) consult one another in French while deciding whether to take Leontes up on his offer of support, and Leontes waits patiently; this is something that he has had to learn. In the first act, his impatience renders foreignness – embodied by Polixène – a source of mistrust that might be equated to any number of modern reports of native speakers accosting immigrants for speaking their own language. And Hermione’s facility with French (perhaps she is herself to be understood as a Bohemian) becomes code for a facility with Polixène himself.

Bilingualism becomes the all-important tool of mediation, most seen in Camilla (Jane Testar), the consummate politician, who slips seamlessly mid-speech between languages as she builds trust with Leontes,Polixène, Florizel and Perdita in their own languages, but also asserts her own fluid identity when her own foreignness becomes important – for instance, suddenly switching back to English as she insists to Polixène on her own desire to return to Sicilia. And when Perdita comes to Sicilia, it is Paulina (Andrea del Campo) and then the reawakened Hermione (Ava Darrach-Gagnon) who address Perdita in the French she has been raised in, the women providing the connective links between the English-speaking Leontes and his ‘foreign’ daughter (a particularly moving moment sees Paulina announce Hermione’s resurrection in English, then come close to Perdita to whisper to her in French to approach her mother).

The creativity with language underpins a production that repeatedly emphasises division and unity. Leontes’ authoritarian court is staffed by two intimidating, masked, black-clad figures who stand in for Cleomenes and Dion, and who create a faceless machinery of state that is particularly intimidating when Hermione is arrested, and when messages are passed silently around the court. Hermione herself is placed in a cage for her trial, holding the bars as she defends herself. Leontes seems small within the edifices of authority that he commands, and Daniels’s restrained, emotional performance is perfectly pitched for the proximity of the camera, allowing him to slowly and quietly crack first in his jealousy and then in his guilt. The barriers set up by Leontes are corrosive; following Antigonus’s moving words to the baby Perdita, the Bear emerges and noses around for where the baby has been laid. Antigonus calls to it – ‘Here is the chase’ – only to look and see that it is Hermione wearing a bear skin; the vengeful woman/animal gets a claw to his stomach and carries him off-camera, and when she returns for the baby she is called away again by his screams. In a more benign but fascinating vein, Autolycus shows nothing but confidence in Bohemia as he tricks the Clown’s wallet away from him, accepts money from the revellers and from the fleeing Florizel and Perdita, and jokes with the camera; in Sicilia, however, he is alone and vulnerable, learning meekly of the reunions from Camilla and then being lorded over by the newly-lorded Clown (Toby Hughes) and Shepherd (Keenan). Those who sow division find themselves on the outside eventually.

Unity comes through dance. The production follows in the tradition of all Shakespeare in the Park-style productions with its lush costumes and liberal use of music and dance, which here serves a unifying function beyond language, whether in the stately dances that open the court in Sicilia, the elaborate country dances of Bohemia, or the joyful dances of reunification that bring everyone together at the conclusion. Bohemia, in particular, brings everyone together: as the country-folk dance, the disguised Polixène keeps rhythm and sings, and Camilla produces a trumpet to provide a melody. This celebratory moment is undercut by Polixène’s rage when revealing himself to Florizel and Perdita, but the pull throughout the production is back to the language of shared song and dance as providing healing.

The cut-down production runs to less than two hours, but its efficient choices mean that very little of substance is lost, and the dynamic camerawork does a great deal to flesh out the scenes with reaction shots and some interesting use of depth of field (Leontes turning his back on Hermione while the masked gaoler waits behind her is a great bit of blocking). Less effectively is an unnecessary framing device that places all of the action within a book whose pictures emerge to life in the filmed footage; while this attempts to recast the play as Disney fairytale, the device is too sparingly used to have meaningful effect. The sudden unexplained closing shot of an elderly Leontes stood alone looking at a masked statue of Hermione adds a jarringly melancholy note to the ending, too, as the production suddenly seems to succumb to the ravages of Time.

But more powerful is the final scene, which returns to a particularly splendid part of the ruins that stands for Paulina’s chapel, and where Hermione stands on a plinth with water pouring from it as a fountain. The impressive setting is suitably awe-inspiring, particularly allowing Perdita to seem intimidated by the sacred presence of her mother, but also allowing Leontes to be humbled. And as the couples dance in the courtyard, Sicilia’s ruins once more appear full of life.

Perceptive and insightful review, Peter, especially on the bilingual adaptation. Cheers, Randall .