May 22, 2022, by Peter Kirwan

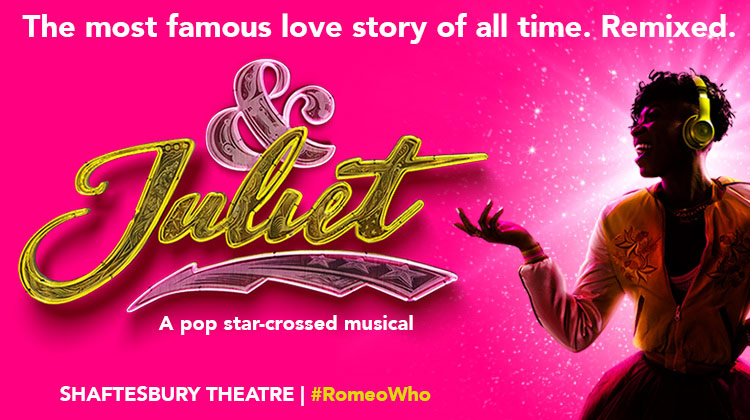

& Juliet @ Shaftesbury Theatre

As jukebox musicals go, & Juliet should have had an easy audience in me. Not only does Max Martin’s over-punctuated back catalogue speak pretty precisely to my teenage years (albeit I’ll be whooping for ‘. . . Baby One More Time’ and ‘Oops! . . . I Did it Again’ rather than ‘Roar’), but ‘Everybody (Backstreet’s Back)’ was the song that made me first decide I wanted to learn bass. Mapping this prestigious canon onto a slice of Shakespearean biofiction and a response play to Romeo and Juliet, in theory, sounds like a stunningly kitsch idea. In practice, while produced to a fine sheen in its West End production, & Juliet felt like a show that had been rushed into production while still a workshop idea, content to go for the easiest possible wins at the expense of quality.

Similar to Lost Dog’s far superior Juliet & Romeo, Martin and David West Read’s show imagined Shakespeare (Oliver Tompsett) finishing writing Romeo and Juliet, and getting a negative reaction to the ending from wife Anne (Cassidy Johnson) and his company of grunge Elizabethan-chic players. Taking over his quill, Anne decided to begin penning a new ending, in which Juliet (Miriam-Teak Lee) decided not to kill herself and instead whisked herself off to Paris with her Nurse (understudy Cassandra Lee at this performance), non-binary best friend May (Alex Thomas-Smith) and April (the role taken by Anne herself), to begin a new love story. Anne insisted that she wanted a happy ending, fed up of Shakespeare continually depicting unhappy marriages. Will, in pursuit of his art, wanted complications, darkness, and tragedy.

Among the various problems, the image of two white people writing the lives of a cast made up primarily of people of colour seemed one of the most poorly thought through. All of the characters in & Juliet were ciphers, and extraordinarily badly written. Not a single cliché of basic #empowerment was omitted; when Juliet finally got to her empowering speeches, there was no trace of irony as everyone immediately started shouting variations on ‘I love that for you!’ and ‘You go girl!’ The quality of the book was the show’s biggest issue by far; structurally, the show operated like pantomime, in its use of very short, efficient plot points designed to create the necessary narrative links to get to the next song, but without any of the charm or wit that characterises good panto. Indeed, when the show did actually manage to find a good pun – such as the brilliant reworking of the Backstreet Boys lyric to read ‘I want Anne Hathaway’ in Will’s apology, and the subsequent remark that ‘There’ll never be another Anne Hathaway’ – the show insisted on stopping to point at its own cleverness.

As such, the show embodied many of the worst characteristics of white entitlement. The real story here was Anne’s; this was her first night out in years away from the kids – she was going to dance, have a big glass of wine, and try not to fall asleep before the interval, deliberately and cannily identifying the target audience for & Juliet itself. Through her dissatisfaction with Will’s version of the play, she was projecting her own dissatisfaction with her life, with a husband who prized his career more than he prized her, and regretting her own life choices – which had never really felt like choices at all – which had left her at home with the kids. In this, there was a genuinely moving story of the kind often neglected by theatre: the story of the woman who feels that she has now been formally excluded from stories, who can’t see a way to create agency over her own life again. The racial semiotics of her then working through these issues with a group of thinly characterised BIPOC avatars, in order to eventually force Will into an acknowledgement of her pain, were at best deeply unfortunate, and at worse a crass and unthinking emblemising of racism that doesn’t understand people who aren’t white as real people at all.

This is to read the show uncharitably; perhaps this is just intended as a good night out? Sadly, the show itself was lacking in several areas. Sound issues plagued the evening, particularly making understudy Christian Maynard as Francois almost inaudible. But more structurally, while the show is blessed with a number of absolute bangers, the orchestration and performances flattened out much of their distinctiveness. Bon Jovi’s ‘It’s My Life’ missed the opportunity to give the newly resurrected Romeo (understudy Rhys Wilkinson – the fact that three of the main eight cast members were understudies at this performance not boding well for London’s COVID situation) a distinctively rock idiom by ramping up the synths to make the song sound more like the rest of the show. And while Lee is a singer of rare talent, the arrangement of all of the songs to suit a breathy, whispery tremolo with massive over-modulation (more Beyoncé than Britney) made most of her songs sound indistinguishable from one another. The drama of the songs as recorded by the original artists here felt flattened into karaoke.

There were highlights, still. When the show actually tried to do something more theatrical with the orchestrations, particularly bringing in the ensemble, it was fun – the whole cast singing ‘Larger Than Life’ to Shakespeare was an early highlight, and while ‘Roar’ started sounding like any of Juliet’s other songs, the building in of the whole cast finally gave it a bit of oomph. And the house absolutely erupted for ‘Everybody’, which the show didn’t even bother trying to fit in narratively, simply staging it as a get-together of the house band before Juliet and Francois’s wedding. The fact that, of all of the songs, this was the one they decided to stage as parody, was criminal. But the songs largely felt static. In several instances, the song (as in ‘Teenage Dream/Break Free’ or ‘Problem/Can’t Feel My Face’) directly contradicted the needs of the scene, thus creating a situation where the song said one thing but then was immediately undone, dragging rather than progressing the slight story. Francois’s use of ‘As Long As You Love Me’ was the nadir of this, the lyrics so nonsensical in their context that Juliet even remarked on this within the show. And with the songs themselves regularly curtailed or deprived of their own climaxes in order to fit into the show, it was hard to even enjoy the songs on their own terms.

Plot-wise, this ‘sequel’ to Romeo and Juliet hewed closely to the original. When Juliet’s gang arrived in Paris, they went to a party being held by Launce (a game Julius D’Silva), a local nobleman looking to get his son, Francois, married. Juliet had a meet-cute with Francois which immediately got too serious (the use of ‘Oops’ here one of the show’s highlights, especially as the song was actually structurally important to what was happening). Meanwhile, Francois also met May, and the two had a stronger connection. ‘I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman’ was reimagined as a transition song, and if & Juliet has one major thing going for it, it’s that it’s an unapologetically trans-positive show. The relationship between Francois and May was one of the sweet things in the show, and the speed with which Juliet and Francois tried to rush into a heteronormative marriage was a nice modern twist on the fateful pressures of Romeo and Juliet. Alongside all of this, Launce and the Nurse – Angelique – turned out to have had a previous relationship, which they renewed (borrowing a lot of Romeo and Juliet‘s situations to do so). And, looking to complicate things, Shakespeare brought Romeo back from the dead, who turned up as a Jesus Christ Superstar runner-up, a full douche, who mooned around the stage as a kind of lacklustre Ghost of GCSE Seminars Past.

The show worked best when it leaned into its metafictional aspects. The quill operated as a kind of magic wand with the ability to instantly change the story, into which both Shakespeares inserted themselves merrily (though a plot point in which Anne snapped the quill, apparently leaving Juliet to her own fate, was then completely undone when Shakespeare turned out to still have the pen and the ability to write new characters into the show, in one of a number of inconsistencies which suggested the incompleteness of the writing). Anne literally conjured up a carriage to whisk them to Paris, in a moment that suggested that this show actually would have worked better as a committed pantomime in which the Fairy Godmother was getting too involved with her charges. Instead of pursuing this, though, the show settled for some quite banal ‘be your own best self’, ‘live your truth’, ‘I’m focusing on me’ affirmations, preferring slogans to anything more complex. The fact that Anne’s ‘crisis’ was resolved by Will literally just saying ‘I love you’, and that even in their projected fantasy, the conclusion still involved Romeo and Juliet getting back together (but just one date at a time) suggested that, actually, the fatalism of heteronormativity was still in full sway.

Anne’s complaint that ‘I just want Juliet to have a choice’ is an incoherent desire to have for any fictional character. This spoke back to the self-serving nature of Anne’s ‘feminism’. What she actually wanted was for Juliet to have a happy ending according to her own values, not choice – indeed, in one of the potentially interesting moments that the show completely avoided committing to, Anne’s insistence on forcing Francois and Juliet to fall in love despite Francois’s attraction to May made her come across as TERFy, in a way that briefly presented Will as the advocate for queer identities that allowed people to have actual choice. Instead, Anne’s eventual desire for Juliet to exercise her own ‘choice’ and independence was answered by a surprisingly conservative set of alternatives that still failed to create literally any identity for Juliet beyond snogging Romeo, and this was perhaps the show’s biggest disappointment of all. While the show clearly played well to a passionate audience, my takeaway was that Juliet deserved much, much better writers than either of these Shakespeares.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply