July 31, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

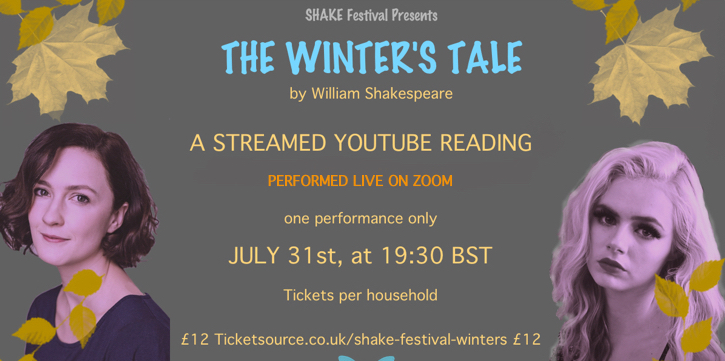

The Winter’s Tale (SHAKE Festival) @ Zoom

Following the initiation of the live online Zoom/YouTube readings of Shakespeare by The Show Must Go Online early in the pandemic, a number of other organisations have worked to put on Shakespeare readings of their own. SHAKE Festival is unusual among them for two reasons: its ticketed entry (as opposed to inviting donations) and its unusually starry casts (led twice by Rebecca Hall, sister of director Jenny Hall). The director’s introduction to this reading of The Winter’s Tale suggested a particular timeliness to the play in its interrogation of abusive men and the destruction caused by strong-man leaders. In practice, the primary interpretive interventions were made by Richard O’Brien in a short but incisive interval talk that picked up on the play’s qualities of breath and made excellent use of Jeanette Winterson’s The Gap of Time. The production itself made few if any interpretive interventions in the play, and instead concentrated on simply speaking the words.

The quality of Zoom-based theatre over the last seventeen months has perhaps spoiled me, but what was most disappointing about the production was the lack of any visual or spatial invention. With the exception of some fake beards for Autolycus, Polixenes and Camillo’s disguises, there was precious little use of costume or props, the actors merely presented in their own clothes against plain backgrounds. This is, of course, understandable for a reading, but harder to understand was the lack of activity. With a couple of exceptions (the experienced Rob Myles as Polixenes, for instance, and a nicely bemused Florizel) there was very little attention given to reactions, leaving the majority of crowd scenes frustratingly static.

The production also made limited use of the Zoom frame, which indeed often worked against any meaningful organisation. For the opening scene (1.2), for instance, two non-speaking attendants occupied the centre of the screen, decentring all the main participants. No differentation was made between Leontes’ asides and the dialogue scene, which rather elided the nature of private speech within the play; even having the other speakers lean away (as Polixenes did) might have at least allowed depth to come into play to help distinguish asides. The compensation for this was that, when Polixenes and Charlotte Hamblin’s Hermione remarked on Leontes’ seeming distraction during his asides, it made clear Leontes’ failure to conceal his own private thoughts.

In many ways, then, the production worked better considered as an audio production, which felt in some ways closer to what the production was aiming for with its spoken scene locations (always an oddly anachronistic eighteenth-century touch) and its very pleasant original incidental music by Oliver Wass and Finn Collinson on harp and recorder. And in the speaking of the text, the quality cast did some fine work. There was some indication of under-rehearsal; one of the performers, in particular, kept confusing the syntax of their speeches in ways that made a mess of the sense. For the most part, though, the company offered nicely varied readings of their lines in ways that captured the musicality of the play.

Some of the most inventive work was done by Mark Quartley as Leontes, especially in the wake of him praising Hermione for persuading Polixenes to stay. As Hermione spoke about when she had last spoken well, Leontes looked pained, as if frustrated that she was spending so much time speaking and desperate to wrest back control of the conversation. Then, left alone with Mamillius (who played alone with toy vehicles in his own Zoom frame), Leontes leaned in closer to the screen, allowing his jealousy to ramp up little by little until reaching a peak at the height of the trial scene. Quartley made for an unusually young Leontes, and the impetuousness and seeming spontaneity of his jealousy flowed naturally, as did his penitence on hearing of Hermione’s death.

Quartley’s Leontes was surrounded by dignified counsellors, including the beautifully spoken Paulina (Wendy Morgan), whose measured, steady tone both grounded Leontes but also determined the conditions of his repentance; the dynamic between them made it easy to understand Leontes’ acquiescence. Michael Mears was a kindly Antigonus, who particularly came into his own during the evocative description of Hermione’s ghostly appearance to him, and who bore the weight of carrying the tragic consequences of Leontes’ actions. And Leo Wringer was a consistently moving Camillo; his restrained reaction to Leontes’ murderous orders and castigation of him demonstrated his distress and sorrow even as he silently took on himself the brunt of Leontes’ wrath.

The cuts throughout the first half streamlined the action to accelerate the progression of Leontes’ jealousy towards the trial. Casualties included the whole of 1.1 and Cleomenes and Dion’s scene returning from the Oracle. More surprisingly, the Bear was cut – and indeed, the Shepherd appeared on screen to begin his musings on teenagers before Antigonus had even been eaten, eliding the play’s most infamous moment of staging into non-existence. The lack of attention to staging – or even to the dramaturgical beats – frustratingly deprived the play of its key stakes. While the cast did their best to infuse lines about the deaths of Mamillius, Hermione and Antigonus with shock and pathos, the lack of reaction on-screen, or space to give the audience something of their own to react to, made the more pivotal actions of the play seem somewhat rote.

The Bohemia scenes managed to generate a little bit of life. Tim Fitzhigham’s Autolycus was particularly good, giving a much fuller and more embodied performance than most of the rest of the cast – ducking out of frame when sought by Camillo, strumming guitar and leading three-part ballads, and jumping between a wide variety of fake beards and silly voices as he flipped between his various performances; by contrast, when listening to the reports of the three Gentlemen of the reunions, he seemed older, abashed, as if the character’s energy had been left behind and his encounters in Sicilia had gone some way towards humbling him. Elsewhere in Bohemia, Myles used Polixenes’ disguise to great effect to lull Perdita and Florizel into a sense of security, before tearing off his beard and unleashing a thunderous assault on his wayward son. The dynamic between Oliver Cotton’s Shepherd and Alistair Hall’s Clown was also a pleasure, the two creating a warmth that established an effectively distinctive tone for Bohemia right from Antigonus’s death.

The production reserved its only technical innovation for the final scene. When Hermione’s statue was revealed, Hamblin appeared as a screenshot rather than the actor needing to hold herself still. While this might be something of a cheat, it had the desired effect, as I found myself holding my iPad close to my face and scrutinising the image carefully to see if this was simply a very life-like picture or a woman breathing in real time. Coupled with Morgan’s measured, emotional delivery and the live music that played, this was the scene that managed to capture something of the finale’s sense of wonder as the screenshot suddenly became the living actor. In this moment, the production showed something of the potential to transcend a quality reading and create something that made more holistic use of the medium, realising The Winter’s Tale‘s spectacular, as well as oral, qualities.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply