August 6, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

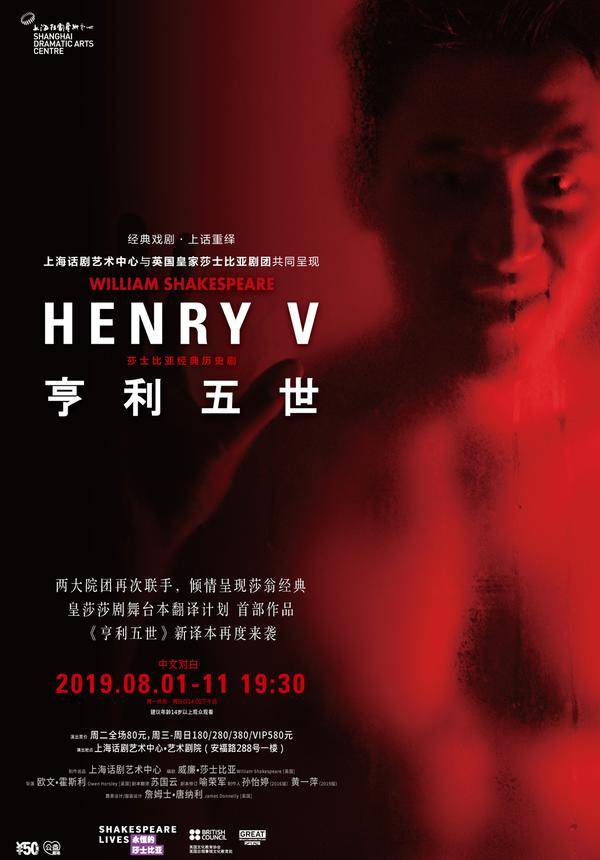

Henry V (RSC/Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre) @ Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre

The RSC’s Folio Translation Project, designed to create new Chinese-language translations of the canon, began in 2016 with Owen Horsley’s production of So Kwok Wan’s translation of Henry V. Made available to delegates at the World Shakespeare Congress, the film of the production captures a lean, contemporary take on the play that is unmistakably RSC in its aesthetic (dark backgrounds, metal boxes, classical-contemporary costuming; James Donnelly’s design could be lifted direct from the Stratford main stage) but with a dynamic use of space and ensemble movement that is very much its own.

This Henry V is about the theatre of power and authority. Around the far edges of the stage can be glimpsed make-up tables and costume rails, framing everything that happens within the square of dirt that makes up the main stage as performance. In the centre of this stage is an enormous metal and glass box, illuminated from the inside, that serves as a locus of authority throughout the play, creating a clear spatial division between what is within and what is without. What is within is Henry (Lan Haimeng) who, for the play’s first half, remains almost entirely within the box, clearly separated from those he commands. And with Henry visible in the box even while the focus is on those who are outside, the production emphasises the scrutiny that this young king is under as he prepares to take his country to war.

Appearances are key in this world. Sycophantic hangers-on surround the French nobility: the Dauphin (Guo Lin) has three who clap and laugh at the Dauphin’s affected, arrogant dismissals of Henry, and Princess Katherine (Fan Yilin) similarly has a trio of maids who are a captive and appreciative audience for her tongue-in-cheek approach to her language lessons. The sixteen-strong ensemble often swell the scene, meaning that Nym (Zhao Haitao) and Pistol (Chen Wenbo) are playing to an on-stage crowd as they square up against one another in their opening confrontation, while Montjoy (You Mei) quietly enjoys defying Henry in front of his own men, and makes a point of forcing them to part for her as she leaves their first encounter in France. This production features very little fighting; instead, it’s the soft power of who gets an audience, who is performing for who, that drives the production’s dynamics.

For no-one is this as true as it is for Henry. Bathed in the cold bright glow of the glass-sided box, every gesture and decision that Henry makes is available for scrutiny, and he has to work with that in consolidating his own power. Lan Haimeng is a confident, charismatic performer, and Henry’s arc allows him to gradually show more and more of himself. When presented with the tennis balls, he reacts with dignity even in his anger, relishing his pronouncements as he makes his decision, with full approval of the assembled religious and political leaders. But it’s in his handling of the conspirators that Henry’s command of the theatre of state comes into clearest focus. Henry loudly proclaims the pardoning of the man who railed against him, and then makes to leave the box. He lets the conspirators condemn themselves as they stop him leaving, telling him he is being too lenient. It is this action that allows Henry to turn back, showing him to be a man of mercy but also of firm judgement, as the men are hoisted by their own petard.

As the action moves to France, the box begins opening up, but Henry still seems trapped within it. At the gates of Harfleur, Henry roars his troops on, but is physically stuck in the box, waving his soldiers past him, and not able to directly connect with them. He is with his men, but not yet one of them, and this separation is both agony and necessary. The importance of the separation is apparent at the conclusion of the first half, as Fluellen (Ren Shan, playing the Welshman as the play’s main comic role) tells Henry of Bardolph’s forthcoming execution. Henry reacts visibly to the news, initially walking away within the box as Fluellen rambles on until someone shushes him. But Henry turns back, holding out an authoritative finger, pronouncing his firm decision. It is then, as he reacts to Montjoy’s taunts, that he finally leaves the box, stepping down to Montjoy’s level as he asks forgiveness for the arrogance that France has instilled in him. Following the interval, this decisive movement is then followed by his disguised walk among the men of his army, and from this point on Henry moves more fluidly between the authority space of the box and the battlefield that he shares with his troops.

For the second half, the box is moved to stage left and is opened up further, with a large platform jutting out towards centre-stage. This more open environment announces the English camp, evoked by the members of the ensemble moving in anxious synchronisation as they sit and wait. Henry moves freely around the ensemble while shrouded in Erpingham’s cloak, and sits on the lip of the platform with Williams and Bates to debate the right of their cause. This is an important transitional encounter, followed by a lengthy soliloquy delivered from centre stage. It’s notable that, when Montjoy returns for the final parlay, Montjoy stands on the platform while Henry remains on the main stage with his men, continuing his plunge in charismatic ground-up leadership. The platform remains in use for moments of staged power, as when Henry allows Fluellen an undignified rant against Michael Williams (Bao Er) following their confrontation; Henry’s adoption of the platform allows him to present his judicious management of the conflict, while reminding both Fluellen and Williams of their own places.

The loosely modern setting sidesteps any direct engagement with geopolitics, the costume and non-specific locations aiming for a more general interrogation of the politics of power. This does somewhat mute the impact of the play’s linguistic politics. I’m no Mandarin speaker, but Fluellen, MacMorris (Guo Lin again) and Jamy prompt laughter from the Shanghai audience when they speak, which suggests that an element of accent politics remains in the translation. But the French scenes remain in French, rather than the French being translated to a language with more specific historical tension with Mandarin. While I’m sure there are nuances I’m missing, the coding of Mandarin as English and French as French seem to me to further dislocate the play’s wrestling of language from its edgier implications. What is more important here is the return to an understanding of the theatre of the wooing. Katherine is required to play her part, and Alice (Fu Yawen) has considerable agency as she prevents Katherine from storming out early in her conversation with Henry. Henry, in turn, relaxes and begins enjoying himself, even eliciting an audience response to his ‘can any of your neighbours tell?’ Both Henry and Katherine are playing for appearances, and this becomes momentarily uncomfortable as Henry physically chases Katherine across the stage for a kiss, prompting Alice to have to block him from approaching her mistress. But when Henry announces an end to performing for other people’s sake, as they will be the makers of customs, it is Katherine who runs across the stage to kiss him. What Henry appears to offer here is a shift away from the theatre of politics and towards doing what is true.

War is both theatre and actual violence, and this is understood by both sides. The French and English both have strong women in leading positions, Exeter (Xie Chengying) and Constable (Xu Manman), who are the voices of honourable action on both sides. The French King (Gao Hongliang), like Henry, tends to occupy the box and remain relatively quiet, in contrast to the preening Dauphin who remains lower on the main stage as he boasts and vaunts. Both sides talk up success; but it’s in the exercise of power that words become hollow. Henry’s aggression as he enters Harfleur is followed up during the Battle of Agincourt by the unified image of soldiers moving in synchronised drills, drumming and stamping while the French fall into disarray, crying out in shame as they are routed. And the hard choices of war are theatricalised: a musical crescendo climaxes with Henry announcing the execution of the French prisoners, who are kneeling in a row and stand up as their English captors’ swords swipe down; as they move offstage quietly, Exeter brings forward the anorak that the Boy (Liu Yuting) had been wearing. The sombre moves cut through the noise of war and focus on the distinction between the performance of words of war, and the performance of the acts that decide the war.

This Henry V is a collective act of storytelling, the ensemble of sixteen sharing the lines of the Chorus (Henry himself speaks the final words) and making the space of war through gesture and voice. If the story feels dislocated in time, it still manages to suggest something about the way in which power is won and sustained through acts of performance that translates into the new context; and this lean, energetic retelling of history decentres English itself as the vehicle for retelling English history.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply