February 18, 2015, by Oliver Thomas

Laughing at Poor People

Dr Helen Lovatt reflects on teaching Martial 12.32, a poem about the eviction of Vacerra.

There is a lot of vitriol aimed at the poor these days: skivers, scum, slackers. It’s all their fault, apparently, that they don’t have enough to eat, or that they have to live on the streets and beg. They have far too many children and can’t support them. It’s even worse, of course, if they are immigrants from another culture. Send them back where they came from, or let them die.

But things have come on a lot since the Roman period, haven’t they? I mean, life was cheap then, and there was no welfare state. The voices of the poor are often inaccessible, although we can get some sense of them from inscriptions, as Peter Kruschwitz presents in a very interesting post here. But most of what remains is image presented by those who look at the poor from a distance.

When my students and I read Martial 12.32, which describes the eviction of what seems probably to be a Celtic family, it all sounded eerily familiar.

O disgrace of the first of July,

I have seen you, Vacerra, I have seen your baggage

(whatever wasn’t kept back in place of two years’ rent)

which your wife with her seven red plaits is carrying

and your white-haired mum with your huge sister.

I thought they were Furies who had emerged from the night of Hades.

These come before and you follow, dry with cold and hunger,

not more pale than fresh box-wood,

an Irus* for your times.

You would think the Aricine hill** was on the move.

A three-legged bed and a two-legged table are going too

and a lamp with a cornel-wood bowl,

a broken piss-pot wees from its mutilated side;

the neck of an amphora supports a green-stained stove. …

…not lacking was a pot full of that shameful resin, your mother’s,

with which Summemmian*** whores wax themselves.

Why do you seek a house and scorn the bailiffs,

when you can live, Vacerra, for free?

This procession of baggage is just right for a bridge.****

The humour in this poem comes from the incongruity of the poor man with his retinue of poverty and lack: he has a baggage train like a king, but made up of things that no one could possibly want, and what is more it is carried by his women-folk. This is why scholars think he might be intended to be seen as a Celtic immigrant: his wife’s exotic hair-style and red hair, the size of his sister, the fact that the women seem more manly than the men. The exaggerated horrors of his possessions are capped by the implication that his mother, despite being white-haired, is a prostitute: poverty and sexual immorality are frequently linked. The final pay-off of the poem ironically claims Vacerra is better off not bothering to find somewhere to live: he can live for free on the streets. Lucky him.

There is no embarrassment in this poem, no kindness: we are meant to find him disgraceful, to disapprove of him for being poor. The poverty itself is funny.

We need to look carefully at our own attitudes towards poor people: poverty is not a moral state; people are not being punished by the gods with misfortunes. We cannot simply discard and dehumanise people who are not like us. The discomfort in reading this poem for me is that we are much more like the Romans than we would like to admit.

* Irus = a beggar who fights Odysseus in Odyssey 18 and is beaten and evicted.

** Aricine hill = a notorious place where beggars live in Rome.

*** Summemmian = from a notorious red-light district in Rome

**** Beggars were also to be found living under bridges.

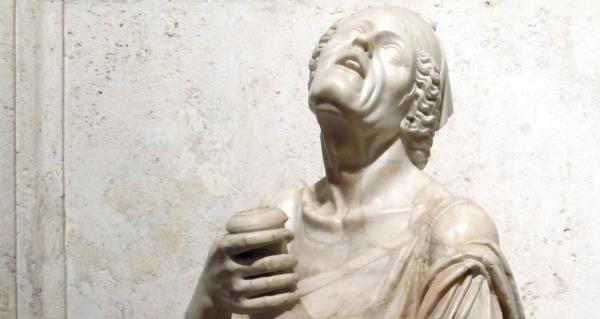

Image: Roman copy of a Hellenistic sculpture of a drunken beggar woman, from Wikimedia Commons.

A lovely piece, thank you Helen. How times haven’t changed! I’ve included a reference to your post in my own recent blog on inscribed epigrams of Rome’s poor, which you can find here:

https://thepetrifiedmuse.wordpress.com/2015/02/15/the-faint-voices-of-the-poor-of-ancient-rome/

Thanks Peter – great post! It’s interesting how poverty is all relative, and Martial himself calls himself poor, but that (presumably) is the sort of virtuous poverty that people are happy to advertise. I think it is the mixture of poverty and morality that is so poisonous. Dickens is also very interesting for reflection on all these things.