February 13, 2015, by Oliver Thomas

Back to the Future

Katharina Lorenz revisits Percy Gardner’s views on Classics, teaching ancient art, and changing the world.

“If anything has been proved in the history of education during the last half century, it is that mere technical instruction in detail does not produce the highest efficiency. It is here that many so-called practical men are mistaken. The practical is often confused with the obvious, and those who see only the obvious see a very little way.” Gardner (1903) p. 64

Intellectual history is the history of institutions and their impact on knowledge production. This at least was the key message of my guest seminar this week in one of the Nottingham Classics department’s MA modules, Researching the Ancient World. My session focused on the history of scholarship of Greek antiquity, specifically on Percy Gardner’s 1903 manifesto “Classics at the Crossroads” and the role of studying Greek art in British Classics.

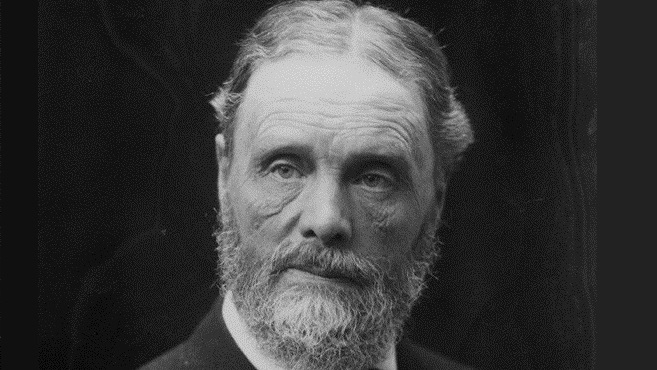

Percy Gardner (1846‑1937) certainly had a good understanding of Classics. A Classics alumnus of Christ’s College Cambridge, he was the first to hold the Oxford Lincoln and Merton Professorship, a chair in Classical archaeology created in 1887. Gardner had previously worked in the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum, and had held the Cambridge Disney Chair of Archaeology from 1879 to 1886.

Gardner wrote the manifesto not least in response to the arrival in Oxford in 1902 of the first holders of Rhodes scholarships – a grant scheme for international students set up by the British industrialist Cecil John Rhodes. Pointing to the much more advanced developments in higher education on the continent and in the USA, Gardner advocated in his manifesto – among other things – a greater focus on the material remains of the ancient world, specifically the study of Greek art which at that point was little realised in British Classics.

Reading Gardner in 2015 may seem an uncomfortable experience because we are still grappling with some of the problems he describes. He talks about exams which appear as an end in themselves, not a means of furthering knowledge and understanding (p. 53); he laments the lack of flexible time within the curriculum for the students’ independent research (p. 47); he warns of the detrimental effects of tailoring university curricula too closely to the job market (pp. 21-2); he even points out the importance of giving lecturers room for their own research, so that they can be truly inspirational teachers (p. 34).

But reading Gardner in 2015 might also serve as a source of inspiration. Gardner was able to implement some of the changes for which he had so fiercely argued: upon his retirement from Oxford, he had brought together an impressive apparatus for the study of Greek material culture, including a research library and a collection of plaster casts of ancient statues. This along with similar resources in other UK departments helped to give the study of material culture a new standing in British Classics, reflected to this day not least in the many courses and modules in this area across UK institutions and acknowledged in the assessment of the discipline in the recent REF2014 exercise.

Gardner changed the discipline of Classics because he believed in the skills that come from its study – “the power of judging evidence, the comparison of authorities, the sifting of facts, and the realization of the past life of the world” (p. 28) – and their importance in preparing for life, in a professional and a spiritual sense. They are skills which will serve us well in an ever-changing world.

Image credit: Percy Gardner, by Walter Stoneman. 1917. ©National Portrait Gallery, London (CC licence obtained).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply