February 15, 2018, by Helen Lovatt

Russians as Spartans? – or Putin the tyrant?

Edmund Stewart on Boris Johnson’s latest allusions to the ancient world

In a recent interview with the Times, British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson once again looked to the ancient world in an effort to explain modern Russia and its relations with the West.

“I was reading Thucydides’ history of the Peloponnesian War. It was obvious to me that Athens and its democracy, its openness, its culture and civilisation was the analogue of the United States and the West. Russia for me was closed, nasty, militaristic and antidemocratic – like Sparta.”

The Greek historian continues to be as influential as ever in the minds of today’s statesmen and has even given his name to the so called ‘Thucydides trap’. This is the doctrine that current and emerging powers are inevitably drawn into conflict. The resulting comparison between ancient Athens and Sparta and the modern USA and Russia or China is truly disturbing.

Oligarchs and Tyrants

Yet is this equation between the militarism of Sparta and the belligerence of Putin in the Ukraine and Syria truly warranted? The Peloponnesian War, as Thucydides describes it, saw a clash between proponents of two different constitutions, democracy and oligarchy, each backed by two major powers, Athens and Sparta. The modern battle of ideologies – between democracies who look to the USA for leadership and the dictators, like Bashar al-Assad, who depend on Russia – resembles superficially the world of Thucydides. But that does not mean that Sparta is like modern Russia. On the contrary, Sparta was an oligarchy with a balanced constitution, by which power was distributed between a number of parties, including not one king but two, as well as the five ephors elected to represent the citizen body. In Russia, on the other hand, one man holds a grip on power that is almost total: Vladimir Putin. Since 1999 he has based his legitimacy on legal magistracies: the positions of Prime Minister and President of the Russian federation. Yet in reality his power rests on the theft of property, both public and private, the corruption of the judiciary and the use of force, as Garry Kasparov has well documented. He has most probably ordered the murder of opponents, such as Boris Nemtsov and Alexander Litvinenko, and imprisoned others, such as Mikhail Khodorkovsky and, most recently, Alexei Navalny. Russia was certainly never a democracy, but it was once an oligarchy, in which a few powerful men controlled much of the state’s interests, especially in oil and gas. Putin has further enriched loyal supporters and driven into exile those oligarchs who could not stomach his rule, such as Khodorkovsky. The Greeks had a word for this kind of behaviour too and it is not oligarchy: it is tyranny.

Tyrants in Athens: The Pisistratidae

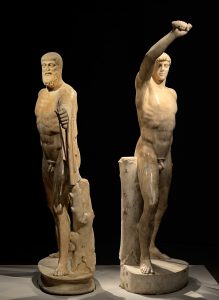

The tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who murdered Hipparchus the son of Pisistratus and were popularly (and incorrectly) credited with freeing Athens from tyranny.

In Thucydides’ day there were few tyrannies, but the Athenians could remember a time when they were ruled in a similar way by one family, the Pisistratidae. Like Putin, Pisistratus did not claim to rule the state or own the title of tyrant. Instead he and his family monopolised the key magistracies in Athens and shared them with other powerful oligarchs, particularly the Alcmaeonidae. But as in modern Russia, this pretence of legitimacy served to strengthen their position and was combined with the judicious use of occasional force. In the end, the Alcmaeonidae were exiled too. The tyrant was not someone who held a political office, like a king or president, but merely a man who desired power and wealth to such an extent as to be eventually willing to commit any crime to soothe his greed and the inevitable fear of retribution. Thus the chorus of Sophocles’ play Oedipus the Tyrant tell us that ‘hybris (outrage) breeds the tyrant’, much as Lord Acton held that ‘power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely’. The former Soviet dissident and Israeli politician Natan Sharansky has shown, in his book The Case for Democracy, that tyrants generally exhibit this common pattern of behaviour, that they support each other in their struggles with their own populations and that they are inherently hostile to democracies and any who oppose their will. By studying ancient political history, as my students do in the Greek Tyrants module at Nottingham, we can see that the tyrant is a figure found not only in many countries, but also in many ages. It is even possible that the Greeks were more alive to the dangers of tyranny than today’s democrats.

Much of this article is outrageous!

1) “between democracies who look to the USA for leadership and the dictators, like Bashar al-Assad, who depend on Russia”

—And who in the region is trying to overthrow Assad violently? The Wahhabi monarchies (Saudi Arabia and Qatar), the Jewish ethnonationalist State (Israel), and the Islamist republic of Turkey.

2) “Sparta was an oligarchy with a balanced constitution, by which power was distributed between a number of parties”

—Russia is an oligarchy with a constitution in which power is distributed between a number of parties. Putin does not have total power. There is factional competition. If the author read anything serious about Russian politics, the most basic literature going back 15 years would refer to disputes between the siloviki (securiity services and those with similar mindsets) and business interests (< i.e., the actual oligarchs who have not yet fled). Crudely, Medvedev is more representative of the oligarchs and Putin of the siloviki. The West works with the oligarchic faction. The West has given shelter to oligarchs (actual thieves and murderers) who defected – Boris Berezovsky was plastered all over the BBC for years.

Let's be honest – the US and UK are also oligarchic countries with some balance of powers. The EU is an oligarchic entity.

3) "Yet in reality his power rests on the theft of property, both public and private, the corruption of the judiciary and the use of force"

—All States are based on theft of property and violence but justify themselves by providing order and normalisation. The grand theft of property in Russia occurred in the 1990s under Yel'tsin with the support of the Western "democracies". The US sent a coterie of Harvard advisors to advise Yel'tsin on neoliberal policies and they made out like bandits – both for Harvard's endowment and personally. I never noticed British banks complaining about looted wealth being invested in the City or in offshore accounts. I never noticed the UK really caring where the Russians who bought up much of Chelsea got their money. It's absurd to blame Putin for the economic rape of Russia.

4) "He has most probably ordered the murder of opponents, such as Boris Nemtsov and Alexander Litvinenko, and imprisoned others, such as Mikhail Khodorkovsky and, most recently, Alexei Navalny."

4a) Nemtsov is a politician who had a lot to do with the theft of property but by the time of his shooting he had 1% electoral support. It's like accusing Obama of wanting to off Ralph Nader or David Cameron of trying to kill Nick Griffin. It's not worth the trouble. Liberals are not the "opposition" in Russia – they are a tiny force with appeal only in the centre of Moscow and St Petersburg among the wealthy (< the people who might have profited from the theft of property and judiciary corruption).

4b) I don't know about Litvinenko but the fact is that he was a defected spy and probable double agent and such people often meet violent ends.

4c) Khodorkovsky was an actual thieving, murdering oligarch. Having begun as head of Komsomol(!!!), he survived the first oligarchic purge by making himself useful to the Kremlin and then tried to become a political figure. Like other accused oligarchs, his crimes were real – he was no martyr to democracy or political prisoner, but there was corruption insofar as the crimes only became arrestable offences once he made political waves.

4d) Navalny is probably the strongest claim and may be seen as a real competitor but what strikes me as odd in this case is that he rose to prominence by making nationalist noises about immigration as much as talking about governmental corruption. He is also prone to stunts like getting a permit for a demonstration in one place and then last-second organising it in another place – in order to get arrested for the cameras. But if you did the same in London or Paris (or certainly DC) you'd be arrested, too.

5) Kasparov (also a big Komsomol kid in the 80s), who was a founding member of the oligarchic, thieving "Russia's Democratic Choice" party in the 90s, is such a great "democrat" he tried to become FIDE champion via bribes. Is Natan Sharansky some sort of hero of democracy simply for agitating for his fellow Jews to emigrate to Israel? He believes that European Jews have the right to show up and simply steal property outright from local Arabs.

Propaganda and the pull to spout approved political lines are not only issues which plague authoritarian and totalitarian societies. It is nothing new in the West – typically, this is what they call "political correctness". However, it disturbs me how recently aspiring academics increasingly feel the need to advertise their geopolitical correctness, Pravda-style, in very unnuanced ways. As President Trump says, "Sad!"

Thanks Thomas for your comment, it is always good to hear other people’s opinions on this topic. This is of course a controversial issue and I freely admit that as a Greek historian I am not myself an expert on modern Russia. I have relied instead on the arguments of those, such as Garry Kasparov, who are authorities on this topic. So while I absolutely admit the possibility of error on my part, I do not think that these opinions are ‘outrageous’, or at least my defence will be that the outrage has been perpetrated by many others before me (including, as Trump would say, the sad ‘mainstream media’).

In comparing the past with the present, there is always the danger that such comparisons will become overly schematic. I would only note that this article was itself an attempt to nuance a different schema made by Boris Johnson. The opposition between democracies and dictatorships is, I admit, overly simplistic and does not take into account exceptions such as Saudi Arabia. It is, however, legitimate to observe that democracies very rarely go to war with each other but frequently do so with dictatorships and that the alliance between the USA and Saudi Arabia can be explained to some extent as the result of the ongoing conflict between the Saudi kingdom and Iran. The foreign secretary’s allusion to the Peloponnesian War is thus broadly justifiable.

I do not doubt that some of Putin’s opponents, such as Berezovsky, were themselves corrupt and they certainly merit the title ‘oligarch’. My point was that a tyranny, on the Greek model at least, is a state where one oligarch has managed to successfully suborn, intimidate or drive out the other big men. This is broadly what seems to have happened in the Russian case. But then, if all are corrupt, why are not all brought to trial? And I would certainly not object if sanctions on Putin’s supporters were increased and if their assets in Chelsea and elsewhere were frozen, as you suggest. It is widely believed that Putin is using corruption cases not to increase transparency and further good governance, but to silence and imprison his opponents. That the judiciary serves the interests of the regime is easily demonstrated by the case of Andrey Lugovoy. He had a definite case to answer in Britain for the murder of Litvinenko, yet the Russian state refused his extradition, hindered the British police’s investigation and then gave Lugovoy a medal. Perhaps this is because the only possible source for the poison that killed Litvinenko was itself the Russian state. This is not an impartial system that follows due process. Again, the comparison with the Greek experience seems appropriate.

There are clear differences between democracies, such as the USA and Britain, and dictatorships such as Russia. (I agree incidentally that the EU is an oligarchy of sorts, but it is at least one in which opposition and freedom of expression are tolerated). In democracies the offices of opposition groups and opposition media are not regularly raided by police, as has been Navalny’s experience recently. Not all states are based on theft, contrary to what Marx might have to say on the issue. Property rights in western democracies are designed to prevent or at least deter theft and there is a world of difference between legitimate business in a free market and the widespread money laundering and extortion perpetrated by the Russian mafia. Such arguments of moral equivalence were used by the Left to justify the USSR before its fall and they are no more convincing today. The hypocrisy of your opponent is no justification for your own behaviour, and in fact the West is most susceptible to this kind of rhetoric because of a genuine concern for human rights. It was supposedly Lenin, after all, who coined the term ‘useful idiot’. I would not pay any attention to polling data out of Russia, given the absence of a free press and the ongoing persecution of the opposition.

Finally Natan Sharansky was imprisoned in the Soviet Union simply because he did not want to live there. The USSR no longer exists because millions of people shared his opinion. Yes, I would call him a hero of sorts for playing a small part in bringing down a regime that enslaved and starved all of Russia and half of Europe. In the same situation who knows how either of us would have behaved, but thankfully because we live in a democracy we may never need to find out. And whatever the faults of Israel, it is the only true democracy in the Middle East. Jews are also entitled to a place on earth where they can practise their religion freely, something that was not possible in Soviet Russia.

I am gratified to hear that my views are ‘politically correct’ or even ‘geopolitically correct’. Again it suggests that if I am wrong, which is possible, at least I am in good company. But I certainly would not wish to stifle debate, ‘Pravda style’. Argument is always better than outrage.