January 13, 2013, by Warren Pearce

Public remaking science? Seeing Sandy, science and climate change

I wrote just after Hurricane Sandy about the tussle between literalism and lucidity in linking the disaster to climate change, contrasting the careful language used by some academics with the ‘tabloid’ simplification of publications such as Bloomberg Businessweek. Since writing that post, some data has emerged potentially shedding more light on these rather muddy waters.

The weak scientific link between climate and weather

Firstly, there was the unauthorised leak of a draft report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). While this is not the final approved version, it seems reasonable to assume that the content is not too far from what will be published in the final report. The report summarises the latest thinking on the links between climate change and extreme weather events, noting that the data no longer supported the claim in a previous IPCC report that there has been an increased intensity in tropical cyclones (see chapter 2 page 5 here).

Second was a US public opinion survey carried out in the weeks after Sandy. When asked whether they trusted what scientists said about the environment, respondents split almost equally between ‘completely/a lot’, ‘a moderate amount’ and ‘a little/not at all’. These results were little changed from a similar question asked in November 2009. Intriguingly, despite these unchanged attitudes to scientists, there appears to be greater public confidence that global temperatures are increasing, and that climate change represents a serious problem for the United States in the future.

The strong societal link between climate and weather

Without any increased public confidence in scientists, one may wonder what evidence lies behind these changes in public opinion. Might it confirm the suspicion that climate change is starting to move from an abstract, intangible issue to one which may be ‘taking place before our eyes’? That is, does extreme weather such as Sandy, the continental US drought or the current Australian heatwave cause people to take the threat of climate change more seriously, despite the scientific community’s reluctance to say that specific events were caused by any increase in global temperature?

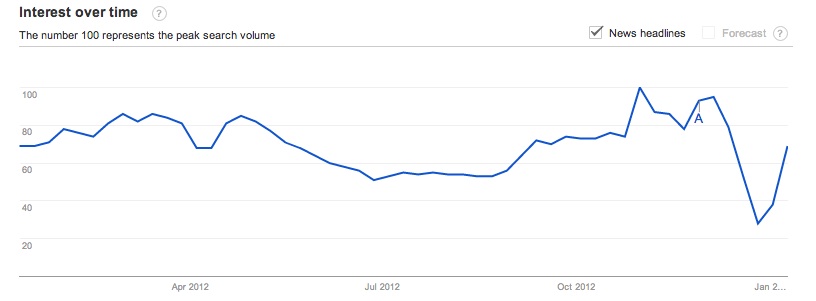

If the answer is yes, then perhaps the media is to blame for this particular public understanding of weather, with the Bloomberg Businesweek cover constituting a powerful ‘Exhibit A’, closely followed by this round-up of extreme weather events in Mail Online India. Indeed, data from Google Trends shows that the peak volume of searches for climate change in 2012 coincided with Hurricane Sandy’s arrival in the US in late October:

Google trends for ‘climate change’: Jan 2012-13

So we are presented with a juxtaposition between knowledge within the scientific community and knowledge within wider society – climate scientists are very cautious about the climate/weather link, the wider public maybe regard it as much more relevant to their understanding. One may respond to this with a plea for more scientifically honest reporting of the link, free of tabloid flourishes or embellishments. However, this implies a rather uni-directional flow of information, that people unquestioningly believe the majority of what they read and see in the media. It is true that it may be a more important source for most than scientific journals, but it does not take into account the process of individuals making up their own minds.

Climate change: a scientific concept reinterpreted in society

What’s more, it may be mistaken to assume that broadcasting more accurate scientific information will play a significant role in this because individuals cannot be assumed to make decisions within a scientific frame of reference. It may be hard to remember within Western societies which strive for scientific rationality, but there are other ways of making sense of the world. For example, as James Burke pointed out in The Day The Universe Changed, Buddhism provides a complete explanation of the world, integral to society, in a similar way to science:

This is not to argue that we should shut our laboratories and live the simple life of Tibetan monks (as pleasant as that might sometimes sound). Merely to provide a stark illustration of how science can be a very minor consideration in individuals’ day-to-day lives, and to show how we might explain behaviours which persist in the face of scientific evidence (such as parents refusing to give their children MMR vaccines).

An everyday understanding of climate seems likely to be a function of the weather, probably in relation to the seasonal norms we expect to experience in a given location. While the category of climate change has been introduced into society by way of scientific discovery, people do not necessarily make sense of it in scientific ways. The notion of a changing climate has become embedded in society but has taken on a life of its own beyond scientific literalism.

Science shapes society, but do people see scientifically?

Returning to the issue of communicating Sandy, this raises some interesting questions about credibility and truth. One of the lessons many have taken from Climategate was that those within the climate debate have to maintain their credibility by avoiding exaggeration or misrepresentation of their work. While this may be true for what one might call a scientific frame, is that the way in which the public make sense of the world? If one acknowledges that while science has played a significant role in shaping modern society, most individuals do not see society in a scientific way, then do the dilemmas in communicating climate change science, gaining agreement on policy and maintaining credibility between the two come into sharper focus?

Many thanks to Peter Broks for the James Burke link.

Image credit: Clarity by joelgoodman

[…] began his blogging year with a reflection on the fall-out from Hurricane Sandy which had hit New York the autumn before and what this meant for public understanding of science […]