October 30, 2020, by Brigitte Nerlich

The social and metaphorical life of viruses

Metaphors are an essential part of science, from doing basic science to engaging in popular science communication. They can be used sporadically; they can be used more systematically to conceptualise a topic, for example the structure and function of DNA; or they can be used in a veritable firework sprinkled across one article.

I once celebrated such an article in a blog post entitled: “Talking organelles: a riot of metaphors”. I wrote that post in March 2019 and said: “I was just in a slump of Brexit malaise when I saw this and thought, ‘oh, there is life outside Brexit, at least in worms and cells’.” At the moment I am in a slump of lockdown malaise. Then I saw another article of this kind and thought “oh, there is social life outside somewhere at least in viruses and phages”.

The article is by Graham Lawton for New Scientist (October 21, 2020). The print title is “The great viral team-up” and the online title is “Viruses have busy social lives that we could manipulate to defeat them” – and it’s actually about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that has given us Covid-19. But unlike other articles about that virus it transports us into a whole new viral world through the medium of metaphors.

It will be very difficult to convey the sheer exuberance of all the metaphors used. To savour that, you’ll have to read the article. The ‘highlight’ of the article summarises it this way: “Viruses are no lone wolves. They have social lives and work together in ways we ignore at our peril”. That’s a novel way of looking at viruses.

What is a virus?

How do we normally think about viruses, if we think about them at all? You might have to think about them when trying to explain what they are to your children, especially in the current situation. You might say something like this:

“A virus is a teensy, tiny germ, way smaller than anything you can see. Viruses can make us sick, but they can’t do anything on their own — they need to live inside another creature (their host) to survive. To do that, they have to get into our cells. The virus enters cells using a special ‘door’ on the outside of human cells.”

And now we come to the new coronavirus in particular: “The new coronavirus also needs a ‘key’ to get into cells. In this case, the coronavirus has a special ‘spike’ on its surface that it uses as a key to open the door. Once inside cells, the virus makes lots of copies of itself. Those copies break out of cells, then infect other cells. At a certain point, there are so many virus particles being produced that our normal cells can’t work properly … and we get sick.”

Here we find already a few metaphors, one of which, copying, is also used in the article I am discussing here. The others (door, lock and key) are not. They are important though; indeed they are key metaphors in biochemistry.

(If you want to know more about viruses in general, this book by Carl Zimmer gets you a foot in the door and unlocks some of their secrets)

What is sociovirology?

As we have seen, explanations of how a virus works focus on what ‘it’ does. The focus is on the individual. When did scientists start to talk about viruses as social entities? I can’t go much into that here, but let’s just say that researchers first started to realise that bacteria communicate and cooperate; then they started to realise that phages, a special type of virus that infects bacteria (and looks rather sexy like “minuscule planetary landing craft”, as Lawton says), also do that; and now they are beginning to realise that viruses also communicate, compete and cooperate.

A new field is emerging called ‘sociovirology’ which studies viruses not as individuals but as social beings. In their article that put sociovirology on the map, Samuel Díaz-Muñoz, Rafael Sanjuán and Stuart West point out that: “Viruses are involved in various interactions both within and between infected cells. Social evolution theory offers a conceptual framework for how virus-virus interactions, ranging from conflict to cooperation, have evolved. A critical examination of these interactions could expand our understanding of viruses and be exploited for epidemiological and medical interventions.”

Metaphors viruses live by

The question is: how can we talk about this new field and about the way viruses interact? The article by Graham Lawton demonstrates some ways of doing that.

To get his/our head around the new social way of looking at viruses, Lawton uses various sources of inspiration: first there are old and new theories of animal and human behaviour, such as game theory and social evolution theory. Second there are the insights from other organisms mentioned already (bacteria and phages), and third, and most importantly, there metaphors that are commonly used in these fields. And sort of embracing all that is our tendency to personify viruses as humans. These metaphors in turn are rooted in a number of well-known experiential source domains:

War: army, army of mutants, kill, attack, fly under the radar

Hunting and crime: hunting, hunting in packs, ganging up on us, lone wolf, lone operators, solo mission, solo assassin, harbouring

Conflict and cooperation: compete, cheat, fraternise, freeload, being selfish/altruistic, snitching, working together, making sacrifices, being self-interested, shutting out

There are also some source domains which are more particular to the fields of genetics and genomics:

Reading and writing: make copies, proofread, proofread new copies, sloppy copiers (churn out all sorts of useless junk); but also stitching

Programming: deadly genetic program

Factories: production plant, genome production facilities, churning out millions of copies of its constituent parts, assemble, minting new genomes

We also get some extended metaphors rooted in economics, game theory and social evolution theory:

Public goods: “The creation of public goods opens the door to cheating or freeloading. As we have seen, this can be overridden by altruism, but that is a rare exception. More often than not, viruses fall victim to the classic ‘tragedy of the commons‘, where everyone hoovers up public goods as fast as possible until they are all gone and everybody loses.” (When trying to find a definition of public goods in biology I found an article by my University of Nottingham colleague James O. McInerney (and Douglas H. Erwin) which you can read here).

What about SARS-CoV-2?

Now we know a bit more about how one can talk about a new way of seeing viruses, namely as interacting with each other. But what about the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2? Can insights into its social life help us deal with it?

There are two issues where the social aspects of viruses might be important: one is the issue of the ‘infectious dose’ – how many viruses does it take to change a light bulb, so to speak. And then there is issue of co-infections and mutations – how may that change the virus, its virulence and its progression? These are all questions that sociovirology is trying to answer.

In order to find answers to these questions, we need to talk and interact with each other, just like viruses do, we might even have to cooperate and compete. And to do that we need language and metaphors. However, as with all metaphors, we have to keep an eye on whether they enlighten our thinking about viruses or obscure it. The metaphors listed above seem to work well at the moment, but comments welcome!

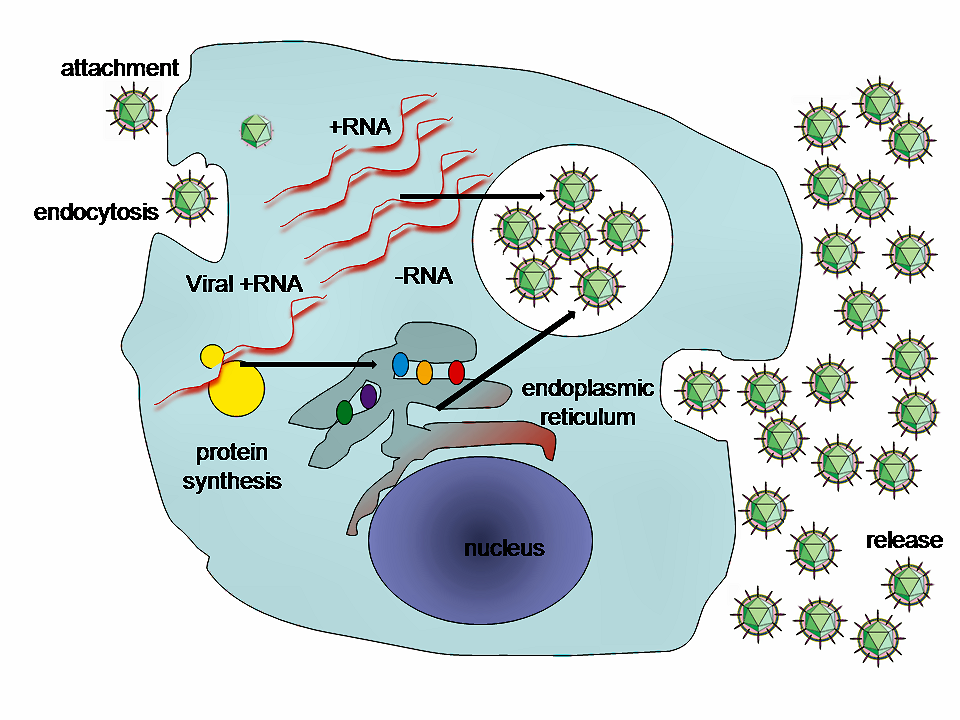

Image: HepC replication, Wikimedia Commons

Thanks for bringing this article to my attention Brigitte. In one sense, ‘sociology’ metaphors are used it seems whenever scientists want to talk about interactions between and among some class of things, e.g. cell sociology, molecular sociology; but it also seems to indicate that the ‘actors’ in these interactions are modified in some way thereby in ways that say lego blocks are not, and they are also collectively able to achieve emergent properties they couldn’t on their own, much like people do when we work together in social groups. Let’s hope this sociovirology perspective bears fruit (to mix my metaphors).