June 15, 2023, by Brigitte Nerlich

Artificial intelligence and existential risk: From alarm to alignment

1956 was a momentous year: I and AI were born. Ok, I was born and artificial intelligence was defined as a field of research in computer science. A lot has happened since, especially over the last two decades; and now speculation is rife as to whether AI might lead to the extinction of humanity. By the end of May 2023 ‘AI as an existential risk’ had become a major talking point. This was nicely illustrated by two cartoons. In one two blokes are sitting in a pub and one says ‘They say AI could kill humans within two years. On the plus side, we can stop worrying about climate change’; in the other a couple are sitting in the living room, the woman reads a newspaper with the headline “AI could destroy humanity” and the man replies “Doing our job already”.

In this post I want to briefly survey the ‘AI as existential risk’ discourse as it has unfolded in the UK press in recent years, see who the main players are and what they say about the risks posed by AI. But, of course, this only scratches the surface. As always, more research needs to be done. (For some info on AI media coverage in Canada, see here)

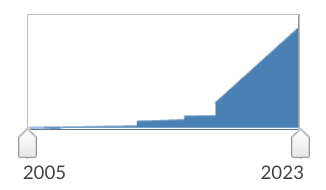

I searched my usual news database Nexis with the search terms ‘existential risk’ AND AI OR ‘artificial intelligence’ on 8 June, when Rishi Sunak’s adviser said that AI could become powerful enough to kill many humans in only two years’ time (reported in many newspapers). I found over 2000 articles published on this topic since 2005 in All English Language News. As you can see from the timeline below (as produced by Nexis), there was a real uptick in interest from around 2017 onwards, probably because of advances in machine learning and deep learning but also increasing ethical concerns about AI and algorithms….

I could not survey 2000 articles for a little blog post though. So I narrowed the search to UK newspapers and got about 200 hits, with the last headline in The Times saying “US will join Sunak summit to rein in ‘existential’ AI risk” and the first headline in 2007 saying “We will have the power of the gods…”.

Between 2007 and 2023 we seem to have gone from speculating about something not yet real to trying to regulate with increasing urgency something about to become real really fast.

I start with 2007 because that’s the year the first article with my search terms appeared in the British press. It should be stressed however, that discussions about the dangers posed by AI have been going on for a long time before that and some of the key players we encounter had contributed to such debates, such as Lord Martin Rees who wrote a book in 2003, Ray Kurzweil and Nick Bostrom who wrote books in 2005, and, not to forget Bostrom’s 2003 thought experiment involving paperclips and existential risk which still haunts discussions today.

2007- AI hype

2007 was still a time of excitement around nanotechnology or rather, as it came to be known for a while, info-bio-nano-cogno-science. This was captured in a programme for a BBC4 series called “Visions of the Future” fronted by theoretical physicist Michio Kaku. In the article about this, we can see that he is not holding back with the hype: “We have unlocked the secrets of matter. We have unravelled the molecule of life, DNA. And we have created a form of artificial intelligence, the computer. We are making the historic transition from the age of scientific discovery to the age of scientific mastery in which we will be able to manipulate and mould nature almost to our wishes.” (The Daily Telegraph, 23 October, 2007)

Kaku had invited various guests onto the programme, amongst them Ray Kurzweil (computer scientist and futurist), Jaron Lanier (scientist and artist who coined the term virtual reality), Nick Bostrom (a philosopher known for his work on existential risk especially relating to AI), Francis Collins (genomics) and Rodney Brooks (robotics).

Kurzweil had been everywhere in the early 2000s talking about the risks and benefits of nanotechnology and in 2005 he had published a book The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology which also covers AI and existential risk (the idea of the singularity is still with us today). In my news corpus Kurzweil’s name disappeared from the pages of the British press after 2007, while Bostrom (founding director of the Future of Humanity Institute established in Oxford in 2005) has been part of the AI and existential risk discourse in the UK ever since.

2012 – AI and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk

We now jump to 2012, the year that ‘existential risk’ was put on the media map in the shape of a new Centre for the Study of Existential Risk set up at the University of Cambridge by Lord Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal, Huw Price, the Bertrand Russell professor of philosophy at Cambridge, and Jaan Tallinn, co-founder of Skype. Some tabloids called the centre the centre for Terminator studies. The centre’s interest focused on “four greatest threats” to the human species: artificial intelligence, climate change, nuclear war and rogue biotechnology. As my corpus consists of articles from the British press, this centre, together with Lord Rees, dominated discussions for some while to come.

In November 2012, the Sunday Times quoted Rees as saying, rather prophetically: “‘One type of risk’, says Rees, ‘comes from the damage we are causing collectively through unsustainable pressures on the environment. The second might come from the huge empowerment of individuals. We are much more networked together and we are much more vulnerable to cascading catastrophes from breakdowns in computer networks or pandemics.’” To this one should add that post-pandemic and post-ChatGPT, Rees said in The Independent on 4 June, 2023 that “AI poses a pandemic-scale threat – but it won’t herald the death of humanity”.

2014 – AI, Transcendence and warnings from Hawking and others

In 2014 four prominent figures in cosmology and AI wrote a piece for The Independent (1 May) inspired by the release of the Hollywood blockbuster “Transcendence” which showcased “clashing visions for the future of humanity”. They argued that “it’s tempting to dismiss the notion of highly intelligent machines as mere science fiction. But this would be a mistake, and potentially our worst mistake in history”.

The three protagonists were Stephen Hawking (theoretical physicist and cosmologist who died in 2018), Stuart Russell (computer scientist and a co-author of Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach), Max Tegmark (physicist, cosmologist and machine learning researcher and president of the Future of Life Institute – which has the ‘goal of reducing global catastrophic and existential risks facing humanity, particularly existential risk from advanced artificial intelligence’) and Frank Wilczek (theoretical physicist, mathematician and Nobel laureate).

The same year Nick Bostrom published his book Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies, reviewed in later years.

2015 – AI and warnings are getting louder

2015 began with Hawking and more than 1,000 scientists signing “an open letter […] warning of the dangers of a ‘military AI arms race’ and calling for an outright ban on ‘offensive autonomous weapons’ (The Sunday Times, 2 August, 2015). Hawking even “warned that the ‘development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race’”.

Sir Nigel Shadbolt, a former colleague from the University of Nottingham and now an AI expert and open science advocate working from Oxford, pointed out that “AI researchers are becoming aware of the perils as well as the benefits of their work.” He stressed that one should keep in mind that “dumb-smart” programs “[d]one at scale” can become “an existential risk. How reflective does a system have to be to wreak havoc. Not at all if we look to nature and the self-replicating machines of biology such as Ebola and HIV.” (The Guardian, 22 January, 2015). But his seems to have been a lone voice in an ever-more alarmist discourse landscape.

In December 2015 the Financial Times reported that “high-profile entrepreneurs and scientists have been sounding the alarm about the existential risk artificial intelligence poses to humanity. Elon Musk, the crusader behind electric-car company Tesla, tweeted last year that artificial intelligence was ‘potentially more dangerous than nukes’”. Musk “described AI as our ‘biggest existential threat’, taking the mantle from the hydrogen bomb” (The Times, 2 August, 2015). From 2015 onwards Musk’s name appeared more frequently in the UK press, alongside Rees and Bostrom.

In 2015 Nick Bostrom claimed that AI poses a greater threat to humanity than global warming and started to speculate about the emergence of sentience in his book Superintelligence. In an article published in The Guardian in June 2016, Tim Adams pointed out that “Bostrom talks about the ‘intelligence explosion’ that will occur when machines much cleverer than us begin to design machines of their own. ‘Before the prospect of an intelligence explosion, we humans are like small children playing with a bomb,’ he writes. ‘We have little idea when the detonation will occur, though if we hold the device to our ear we can hear a faint ticking sound.’ Talking to Bostrom, you have a feeling that for him that faint ticking never completely goes away.”

The bomb metaphor is quite prominent here, as it was with Musk and many others (you can test your knowledge here, nuke or AI). But is that the right metaphor? Discuss!

In December 2015 OpenAI had a first mention in my corpus in an article in The Financial Times entitled “Inconvenient questions on artificial intelligence” which focused on issues around risk and safety regarding AI. It reports that Elon Musk and Peter Thiel were quite worried and that therefore ”they and others have announced a $1bn project to advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole. Their project, OpenAI, will be a non-profit movement that conducts open-source artificial intelligence research and shares its findings with everyone.”

It is ironic that, after November 2022, OpenAI and its progeny ChatGPT would open the floodgates for both everyone being able to use AI and for experts talking about existential risk with heightened urgency.

2017 – AI, specialists warn and innovations accelerate

In 2017 Musk founded a new company, Neuralink, which develops brain-computer interfaces, because, he argued, the “Existential risk is too high not to” and because AI posed “a fundamental existential risk for civilisation” (The Independent, 17 July). Musk and 115 other specialists from 26 countries called for a ban on autonomous weapons. “Musk, one of the signatories of the open letter, has repeatedly warned for the need for pro-active regulation of AI, calling it humanity’s biggest existential threat, but while AI’s destructive potential is considered by some to be vast it is also thought be distant.” (The Guardian, 20 August, 2017)

An article in The Telegraph from November 2017 pointed out that Bostrom argued that “the creation of a superintelligent being represents a possible means to the extinction of mankind”.

There were other, more realistic, advancements on the AI front, around the AI company DeepMind, for example. Machine learning and deep learning were making great strides. As Anjana Ahuja reported in October 2017 for the Financial Times: “Elon Musk once described the sensational advances in artificial intelligence as ‘summoning the demon’. Boy, can the demon play Go. The AI company DeepMind last week announced it had developed an algorithm capable of excelling at the ancient Chinese board game. The big deal is that this algorithm, called AlphaGo Zero, is completely selftaught. It was armed only with the rules of the game – and zero human input.”

2018 – AI and more expert warnings

In 2018 newspapers wrote about a report entitled “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation”, compiled by “26 of the world’s leading experts” that “paints a terrifying picture of the world in the next 10 years. Physical attacks as well as those on our digital worlds and political system could drastically undermine the safety of humanity, it warns, and people must work together now if they want to keep the world safe.” (The Independent, 21 February, 2018)

The report includes input from representatives from OpenAI; Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute; and Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.

2020 – AI and the dangers of unaligned AI

In 2020, at the start of our real pandemic, Toby Ord published a book entitled The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. As the The Guardian told readers in April 2020:

“An Australian based at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, Ord is one of a tiny number of academics working in the field of existential risk assessment. It’s a discipline that takes in everything from stellar explosions right down to rogue microbes, from supervolcanoes to artificial superintelligence.” He regards the chances of existential catastrophe of “unaligned AI” as higher than climate change.

Here we get to a topic that was already hinted at by Stephen Hawking (in my corpus) in 2017 when he said that “The real risk with AI isn’t malice but competence. A super intelligent AI will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals, and if those goals aren’t aligned with ours, we’re in trouble.” (The Independent, 25 July, 2023). I’ll get back, very briefly, to the tricky issue of alignment at the end of this post.

2022 – AI and human stupidity

In 2022 Rees co-authored a House of Lords report on “Preparing for Extreme Risks: Building a Resilient Society” and had a book out in paperback entitled On the Future: Prospects For Humanity (hardback 2018).

On 1 January 2022 Andy Martin wrote a long article for The Independent about the slow end of humanity and recounted an encounter with Rees: “I popped round to his house in Cambridge to have a chat with the silver-maned cosmologist about the end times. It’s funny how the semantics of ‘existential’ has shifted in the last half-century. It used to refer to something like a personal sense of angst in the face of pervasive absurdity and death; now it has become synonymous with the fate of the planet as a whole. We’ve gone from nervous breakdown to social collapse.”

In 2022 Rees also published a book entitled If Science is to Save Us, about twenty years after his 2003 book Our Final Century: Will the Human Race Survive the Twenty-first Century. One might think that he is a “doomster” but that would not be true, as he is quoted as saying “We’re more likely to suffer from human stupidity than artificial intelligence.” (The Sunday Telegraph, 18 September, 2022). But he is certainly a major player in the existential risk discourse.

2023 – AI, insiders warn and existential risk discourse explodes

In 2023 a new player entered the field, namely Geoffrey Hinton, one of the many ‘godfathers’ of AI, alongside THE major players of course, the AI ChatGPT itself, the company OpenAI and its CEO Sam Altman. Things got hotter in the press. Hinton, a neural network expert who worked for Google, quit Google and warned of the existential risk of robotic intelligence (e.g. The Independent, 2 May, 2023).

In March, “more than a thousand eminent individuals from academia, politics, and the tech industry […] used an open letter to call for a six-month moratorium on the training of certain AI systems” (Financial Times, 1 April, 2023).

At the end of May, a group of leading technology experts from across the world warned that artificial intelligence technology should be considered a societal risk and prioritised in the same class as pandemics and nuclear wars (see The Guardian, 30 May). That really sat the cat amongst the pigeons.

“The statement, signed by hundreds of executives and academics, was released by the Center for AI Safety on Tuesday amid growing concerns over regulation and risks the technology posed to humanity. ‘Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war,’ the statement said. Signatories included the chief executives of Google’s DeepMind, the ChatGPT developer OpenAI, and the AI startup Anthropic.”

The race for regulation has begun. But how do you regulate something that develops faster than rules and regulations? And what are the actual dangers to look out for? BBC News nicley summarised a state made by the Centre for AI Safety on 30 May (which was not in my original corpus):

- AIs could be weaponised – for example, drug-discovery tools could be used to build chemical weapons

- AI-generated misinformation could destabilise society and “undermine collective decision-making”

- The power of AI could become increasingly concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, enabling “regimes to enforce narrow values through pervasive surveillance and oppressive censorship”

- Enfeeblement, where humans become dependent on AI “similar to the scenario portrayed in the film Wall-E”

2023 – AI, alignment and the dilemmas of regulation and control

On 15 April 2023 The Financial Times published an article entitled “The dangerous race to God-like AI” which reminds us of the title of the article we started with in 2007, but this time it’s perhaps less hype. This article focuses on alignment, a topic related to issues of regulation which now dominate headlines around AI. It states:

“OpenAI, DeepMind and others try to mitigate existential risk via an area of research known as AI alignment. [Shane] Legg, for instance, now leads DeepMind’s AI-alignment team, which is responsible for ensuring that God-like systems have goals that ‘align’ with human values. An example of the work such teams do was on display with the most recent version of GPT-4. Alignment researchers helped train OpenAI’s model to avoid answering potentially harmful questions. When asked how to self-harm or for advice getting bigoted language past Twitter’s filters, the bot declined to answer. (The ‘unaligned’ version of GTP-4 happily offered ways to do both.) Alignment, however, is essentially an unsolved research problem. We don’t yet understand how human brains work, so the challenge of understanding how emergent AI ‘brains’ work will be monumental.”

The question is: How will regulation be possible without not only a solid understanding of alignment between AI and human values, goals or interests, but also a deep understanding of the fundamental and potentially irreducible misalignment between large language models and human values?

And if it’s about alignment with human values, what values and whose are we talking about? And how can we hope for AI and/or LLM alignment with human values when we can’t even align our own political and corporative actions with human values or the public good, whatever that may be!

If you want to understand the alignment issue a little bit more, there is a book by Brian Christian that might help and a really interesting podcast with Jill Nephew unpacking what alignment actually means regarding AI in general and LLMs in particular. This stuff is extremely complicated. But I hope there are people out there that understand it and talk about it. If not, this will not necessarily lead to the end of humanity but it will surely stymie efforts to avoid discrimination, bias, prejudice and more.

When I started to draft this post, I had never heard of alignment, apart from in the context of car tyres. Now I see it everywhere, especially after Jack Stilgoe asked about the origins of the concept on Twitter. I discovered there is even an alignment research centre!

And now what?

Things have certainly changed between 2007 and today. Now, everybody who wants to can play with AI, or rather with AN AI like ChatGPT or similar chatbots. Everybody can opine about the good, the bad and the ugly of this technology. In the meantime, warnings about dangers are getting ever louder, with some more nuanced than others, and experts are exploring in agonising detail ways of both refining and aligning AI/LLMs with human values, but how that can be done ‘responsibly’ is still a mystery, at least to me. Perhaps this new research programme on ‘responsible AI’ will have the answer! One thing is for sure, we need much more research on AI/LLM alignment and safety.

Further ‘reading’

BBC Inside Science: AI and human extinction – good discussion with computational linguist Prof Emily M. Bender from the University of Washington and Dr Stephen Cave, Director at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence (CFI).

Andrew Steele summarises the risks, problems and dangers of AI in a very accessible way in this YouTube video. Also really good on alignment. (I discovered this just when I had finished writing)

And this is really great at discussing the very idea of AI and existential risk, with David Krakauer

Image: Pixabay by gerait

Prof Mark Bishop and others have countered a lot of this hype. in a very public debate. he and Warwick have been sparring v partners on dumb vs intelligent AI for over 30 years. not sure how your searches missed this.