June 3, 2022, by Brigitte Nerlich

Monkeypox

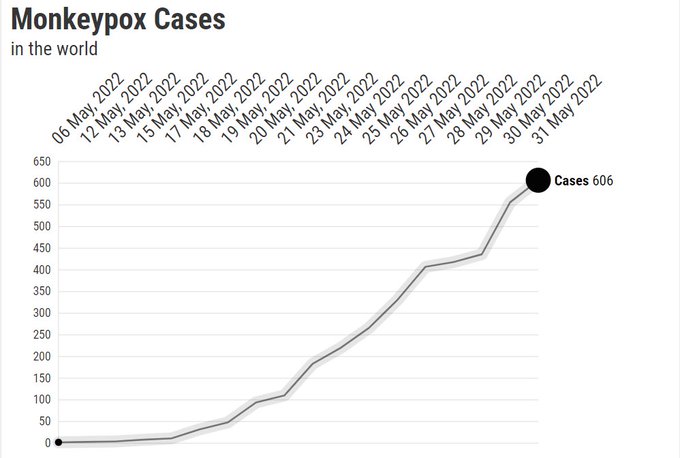

I recently saw these stats (as of May 31, 2022, there are 606 cases of Monkeypox worldwide, with the UK having 190, Spain 136, and Portugal 100) and this graph (see featured image). And I thought: Should I write something about monkeypox? Then I thought: Why not, just to get things straight in my head.

We are, it seems, at the beginning of the end of a global pandemic of the coronavirus and quite fed up with viruses. When a new virus appeared on the landscape, I was not pleased, but soon became quite intrigued. I had heard about monkeypox before, actually during the pandemic, in 2021, when there was as small outbreak in Wales, and some newspapers carried quite alarming headlines of a new killer plague, though, generally, monkeypox was labelled a ‘rare’ disease. (My sister told me that there had also been an outbreak in the US in 2003).

So, what is monkeypox? It’s a virus in the family of the viruses to which the now eradicated smallpox virus belongs, but not as deadly. It is originally a zoonotic disease, which means it usually occurs in animals but can be transmitted to humans and, then, between humans. It was first reported in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, formerly known as Zaire) in the 1970s and is currently endemic only in Central and West Africa. Monkeypox can be contracted from close contact with an infected person, sexual relations, contaminated objects, handling bushmeat and an animal bite or scratch. (For a useful primer, read this post by a historian of medicine)

The first case in the UK was reported on 7 May, but cases were soon dotted all over the world with most of them occurring in the UK and in Spain. By mid-May it was clear that the virus had, by chance, started to circulate mostly in a particular network or community, namely the gay community. The United Nations AIDS body, UNAIDS immediately called for ending an emerging stigmatising language similar to that which circulated during the AIDS pandemic when there was talk of ‘a gay plague’.

When looking at various articles and tweets, I began to think? Ok, so we have a new quasi-pandemic disease. How will governments, the media and people handle this? I can, of course, not write about all of this in one blog post. I’ll just provide you with a random list of what social science, media and communications researchers could think about, as the reporting on monkeypox throws light on a wide variety of issues related to epidemics and infectious diseases.

Naming and terminology

During the coronavirus pandemic there was a bit of head-scratching over how to name variants of the virus without alarming or stigmatising people. Monkeypox dropped into current media conversations out of the blue without such reflection. Nobody remembered that the virus was called ‘monkeypox’ because it was first isolated in monkeys in a laboratory in Europe in 1958, while monkeys themselves do not play a significant role in monkeypox. This does not mean that the name does not provoke alarm, memes and, also, wordplay.

As Mike Lockley wrote in the Birmingham Evening Mail on 27 May in an article entitled “Press are going ape over monkeypox” (by the way, called ‘Affenpocken’ in Germany!): “Monkeypox does not herald the start of an ape-ocalypse, medical chiefs have assured us. It is difficult to catch and the symptoms are mild. As of yesterday, there were less than 80 cases in the UK. Therefore, I’ve concluded the current press hysteria has everything to do with the sinister name. It does not lend itself to comments such as: ‘Just got a touch of monkeypox’, ‘get us some lemsip for this monkeypox’ and ‘put a scarf on, you don’t want to make your monkeypox any worse’.” Ok, cases now are much higher, but still, the name is a problem. [Addition, 11 June, article in Science calling to “replace the current naming system for monkeypox and its so-called West African and Congo Basin strains”]

One more ‘naming’ thing should be mentioned, namely the acronym MSM, which comes up again again in discussions about monkeypox and which might confuse people. In this case it does not mean MainStream Media, neither does it mean, Methylsulfonylmethane, but it means ‘men who have sex with men’. And that leads us to the issue of stigmatisation.

Stigmatisation

It should be stressed that “Anyone with close exposure to monkeypox virus can become infected. By chance the virus infected members of the gay community and, as would happen in any close-knit group, has been transmitted widely throughout that community, potentially though superspreading events. Men who have sex with men are not more vulnerable to this infection, the virus is unable to tell someone’s sexual orientation.” This is, as far as one knows at the moment, not a sexually transmitted disease, but can be transmitted during sex (here is some clarification on this)

These are really important points which we have to keep in mind when trying to stem a rise in stigmatisation, a type of stigmatisation we know all too well from the covid pandemic, where Asian or South African people were the target of stigmatisation, for example. As Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the WHO, said on 1 June: “All of us must work hard to fight stigma, which is not just wrong, it could also prevent infected individuals from seeking care making it harder to stop transmission”.

Given these dangers, it is even more important to work with social scientists than ever before, as Martyn Pickersgill and his colleagues have made clear in a recent article for the Lancet, not only with regard to stigmatisation, but even more so for preparedness, management, information and so on.

Pandemic preparedness

There hasn’t been too much government talk about monkeypox so far, probably in order not to alarm people prematurely. The government issued its first comprehensive guidance on monkeypox on the day I started to think about this post, namely on 30th of May. In other countries too people are starting to worry a bit and some are more alarmed than others. For example, the German health minister Karl Lauterbach is, for example worried that “this virus might be able to thrive in new niche of unvaccinated people. The virus might have spread mostly among MSM so far. ‘But it won’t stay there’, he said, as reported by a key pandemic reporter, Kay Kupferschmidt. This means that good vaccine information management will be important as part of disease management.

Disease management

In hindsight, and having learned from other epidemics, public health people should probably have helped those countries in the past where monkeypox is endemic. As a virologist said on twitter: “As PH officials in Europe and North America race to contain #Monkeypox outbreaks, the response MUST encompass addressing outbreaks in endemic African countries simultaneously. The reason why [we] have the current outbreaks is because those outbreaks were ignored to begin with.” But monkeypox is here now. With foresight we should learn how to manage the spread of the disease from those countries where the monkeypox virus circulates! More generally, to deal with monkeypox, we should learn from both HIV and covid!

That brings us to how to avert a wider spread through isolation and vaccination, for example. Discussions need to be had about isolation and government/community support for those infected, something that was mishandled during covid, and about vaccination to suppress infection.

Denise Dewald, a medical doctor, voiced justified concerns about isolation on Twitter: “Monkeypox lesions take 2-3 weeks to heal. A person is contagious until the lesions are healed. Most people who don’t have paid sick days cannot go weeks without a paycheck If we don’t have emergency financial assistance for people with monkeypox, there will be no containing this”. Governments have to think this through. We have, as Stephen Reicher, a social psychologist, suggests, to create a society in which people can afford to be sick.

Vaccination, confusion and hesitancy

In an atmosphere where vaccination has become a hot topic, confusion needs to be avoided. I was therefore surprised (or rather not) when a UK health official and a government official gave seemingly contradictory information on vaccine, something that can only lead to vaccination hesitancy.

This was what one tweeter wrote on 22 May after watching two interviews on television, one with a medical advisor, another with a secretary of state for education: “Jo Coburn [interviewer] – Will we need to get vaccinated for #monkeypox? Dr. Susan Hopkins (chief medical advisor) – ‘There’s no direct vaccine for monkey pox.’ Nadhim Zahawi [Secretary of State for Education] – ‘Sajid Javid [Secretary of State for Health] has already bought the vaccine’ for monkey pox. #Confused”

Dr Hopkins was not wrong in what she said, but for listeners it was no very clear. She was not saying that there was no vaccine against monkeypox, only that there was not one created to deal with monkeypox in particular, like all the vaccines we now know which had been created to deal with covid. She did not point out, however, that there was the old smallpox vaccine which offers longterm protection against monkeypox. What Zahawi was saying when he said Sajid Javid had already bought the vaccine against monkeypox, was that they had ordered vaccines against smallpox, not a new vaccine just developed against monkeypox……he was not saying that the government had ordered vaccines that don’t exist…. Confusion!

Another tweeter helpfully pointed out “The smallpox vaccination we all used to have protects us against monkeypox. Stopping routinely vaccinating people against smallpox has led to a gradual reduction of community resistance to monkeypox and so its rate if community transmission has grown. There’s enough disinfo around without adding to it. An existing smallpox vaccine is currently used and apparently effective for monkey pox. If Javid has secured adequate supplies then that was the correct thing to do. Zahawi can and no doubt will carry on dissembling.”

And so we come to dis-information…

Information, disinformation, misinformation

As with every outbreak of disease, rumour and conspiracies started to spread very quickly, fired up by covid-related rumours and conspiracies, from lableak to Bill Gates, feeding, yet again anti-vaccination sentiments. A novel twist was that covid had given people the opportunity to learn more about vaccine development and production… This new knowledge (e.g. that the AstraZeneca vaccine uses a chimpanzee adenovirus vaccine vector) now feed, in a very distorted way, into new concerns about vaccination against monkeypox.

And there are of course hundreds of denigrating and misleading memes swirling around on the internet. There are, however, also those who try there best at factual reporting, such as the BBC, from telling people what the disease is and how you can catch it, to how to avoid stigmatisation and to be alert to conspiracy theories. There is also Newsweek, for example and Reuters: “Contrary to social media posts, monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted infection, nor is it only spread between men who engage in sexual relations with other men” – and FullFact and many more. And with facts we arrive at science 😉

Science and uncertainty

During the covid pandemic, science was fast, shared and open, but also precarious, often published in fleeting preprints. It showed how science is usually done, only in fast-forward. With monkeypox, yet again, genomic research has gone into overdrive and what becomes clear again is that science is often done on the knife-edge of uncertainty.

This, for example, is a typical start to a recent article on monkeypox: “This document is an initial report on the observation of an abundance of specific mutations in the 2022 MPXV outbreak and related virus genomes that can be ascribed to the action of APOBEC3 host enzymes. It should be considered work in progress and we plan to add additional analysis and interpretation. We also welcome discussion in the thread below. The analyses here are made possible by the groups and researchers who have shared MPXV genome sequence data”.

Given this fast moving and shifting situation, reporting on monkey pox and providing advice based on science is itself an uncertain enterprise, as this Twitter thread makes clear. So take everything written above with a pinch of salt.

While I was writing this post, I was waiting for Kai Kupferschmidt to tweet out an episode of the Pandemia podcast on monkeypox and it came out just when I was writing the last line of this post! It is brilliant – so informative, including about a lot of unknowns. But it’s in German!

This discussion of knowledge gaps and research priorities by the WHO came out after I finished writing but is a must read for anybody seriously interested in monkeypox.

Image: with permission from Statistics and Data

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply