November 26, 2021, by Brigitte Nerlich

Francis Willughby and me

You have probably all heard of Newton or Halley or Hooke or Pepys … But have you heard of Willughby? I had, vaguely, but I did not look hard enough. They were all early members of the Royal Society (founded in 1660) and involved in a little scandal to which I’ll come later. But first I want to list all the opportunities I had, and missed, to become acquainted with Francis Willughby, a 17th-century naturalist.

The Hall

I live near Wollaton Hall. Wollaton Hall is an Elizabethan country house built for Sir Francis Willoughby (1546/7–1596), an industrialist and coal owner, in the 1580s – not the man I’ll be talking about here, but still – same family. The family “stayed in the house from 1580 to 1925, up to the 11th Baron Middleton, but has been cared for by Nottingham City Council since 1925, when it became the Nottingham Natural History Museum.”

When my son was young, we went there every weekend and, over time, explored Wollaton Hall from top to bottom under the kind guidance of various friendly guides; from the wine cellars and sandstone tunnels below the Hall and the taxidermy room and kitchens, to the roof on the top, passing through all the natural history exhibits of fishes, birds, insects, minerals and more. That is now many years ago and a lot has changed, but our memories of all the specimen are still vivid.

The dog

In our street lives a lovely dog called Willoughby, who at Halloween, turns into ‘Lion Dog’. I knew the name was connected to Wollaton Hall, but I didn’t follow it up. By the way, there are many variants of the name Willughby. “The modern spelling ‘Willoughby’ was adopted by the naturalist’s son Thomas, first Baron Middleton.”

The man

Now who is ‘the naturalist’? It’s Francis Willughby. He was not, as I once believed, the son of Sir Francis Willoughby who built Wollaton hall, who actually had no sons. The Francis Willughby that interests me, was “the third child but only son of [another] Sir Francis Willughby and his wife Cassandra, daughter of Thomas Ridgeway, earl of Londonderry. The Willughbys of Wollaton, Nottinghamshire, and Middleton, Warwickshire, were country gentry with estates in many English counties.” (Family history here).

Francis was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1661 and was a famous “English ornithologist [i.e. he studied birds] and ichthyologist [i.e. he studied fishes], and an early student of linguistics and games.” (Wikipedia)

Oxford and Cambridge

I have worked at the University of Nottingham for many years and have walked along Willoughby Close and past Willoughby Hall, a students’ hall of residence, without taking much notice. I also didn’t notice that in 2016 there was an exhibition about Francis Willughby – how that escaped me, is a mystery to me – drawing “on papers preserved in the Middleton Collection, the family archive of the Willoughby’s of Wollaton Hall, now held by The University of Nottingham”. It “shed new light on the range of his interests, illustrated by images of birds, fishes and plants which were collected in England, Wales and on the Continent to support his studies.”

Years earlier, when I was a Junior Research Fellow at Oxford in the 1980s, working on the history of 19th-century linguistics and scouring the libraries for old books, I might have been sitting accidentally in a chair once occupied by Willughby, as “for a time in 1660 he was reading books on natural history at the Bodleian Library in Oxford” – one can but dream.

In Oxford, I came to know David Cram, an expert on the history of 17th-century linguistics. It turns out, Cram edited Francis Willughby’s Book of Games! What is more, Willughby and Willughby’s close collaborator, the naturalist John Ray, his former tutor at Trinity College Cambridge, were both fascinated by words, dialects and language, and so, in 2016, Cram wrote an article about this fascinating topic (in a book on Willughby that’s worth reading!).

Throughout their lives, John Ray and Willughby travelled and worked together, collecting and studying not only words, but most importantly, birds, fishes and insects, until Willughby’s untimely death in 1672, at the age of just 36 (if you are interested in John Ray, please read this blog post by Thony Christie!). And now we come to the fishes!

The fishes!

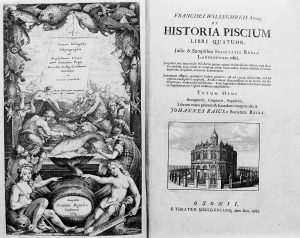

All these strands of my and Willughby’s life suddenly came together when a friend working at the University of Cambridge, Susanne Mesoy, sent me the curious history of Francis Willughby’s and John Ray’s book on fishes, published posthumously in 1686 under the title De historia piscium libri quatuor (History of fishes in four books). This natural history of fishes (which contained 187 plates/illustrations) was printed by the University of Oxford Press with funding from the Royal Society and almost bankrupted it.

How that happened and what that meant for Isaac Newton, a rather better-known member of the Royal Society, as well for as Samuel Pepys (the diarist and then President of the Royal Society who also funded many of the ‘plates’) and Edmund Halley (of Halley’s comet fame, and then secretary of the Royal Society), is a truly ‘horrible history’, as told here in this satirical take in the Horrible Histories TV series – watch and enjoy!

More seriously – let’s see what went on here: The story is told briefly by Bill Bryson in his A Short History of Nearly Everything (2003) – in the context of talking about the publication of Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (“Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy”, better known simply as Principia). After some delays due to a tussle between Newton and Robert Hooke (of Micrographia fame), soothed over by Halley, Newton’s famous work was about to be published by the Royal Society when there was a glitch…..

The society had just “backed a costly flop called The History of Fishes, and suspected that the market for a book on mathematical principles would be less than clamorous. Halley, whose means were not great, paid for the book’s publication out of his own pocket. Newton, as was his custom, contributed nothing. To make matters worse, Halley at this time had just accepted a position as the society’s clerk, and he was informed that the society could no longer afford to provide him with a promised salary of £50 per annum. He was to be paid instead in copies of The History of Fishes.” (p. 74) (A more in-depth account here)

Nowadays, people still remember Newton’s Principia, published in 1687, but the book on fishes, published in 1686) is sadly forgotten, despite the fact that the illustrations it contains are “spectacularly beautiful”. If you are into fishes and/or scientific illustrations, you should have a look here. There are amazing pictures of “pipefish, seahorses, a writhing conger eel, a bearded rockling, a John Dory, tip-knot blenny, garpike, red gurnard and many more” – as Tim Birkhead explains in his book on Willughby the ornithologist entitled The Wonderful Mr Willughby (2018: 121).

The fishermen!

Now you might ask what all this has to do with my usual topics for blogging, related to issues around science and society? I asked myself that question and at first had no answer, apart from: isn’t it an intriguing story and I am so glad I discovered him albeit a bit late in life. But when reading this article, I could actually establish some links to my usual topics. The article is by Didi van Trijp and entitled “Fresh Fish: Observation up Close in Late Seventeenth-Century England.” She writes in the abstract: “This article offers an in-depth analysis of the contributions of fishermen and fishmongers to the creation of natural knowledge.” It shows that the Historia Piscium was not just the work of Ray and Willughby but that it was, in a sense, crowd-sourced. It was partly citizen science.

Here is an overview of the article which you should read (together with Van Trijp’s thesis): “The first part [of the article] explains how Historia piscium took shape as a collaborative project of the Royal Society in the socio-cultural context of knowledge production particular to late seventeenth-century England. The second part takes us to fishing ports and fish markets and discusses how fishermen and fishmongers provided fresh fish for natural historical study, and why this was so important. The third part addresses how these practical men contributed to the identification of, and distinction between, species and sometimes remarked on specific behaviour. The article concludes that the emphasis placed on direct observation as a requisite for establishing an accurate account of species left considerable space for the experience of people of practice in the production of natural knowledge.” Isn’t that interesting!?

In a letter to Robert Hooke written in 1675, Isaac Newton made a famous statement: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants”, referring to other philosophers and mathematicians. Imagine if Ray and Willughby had made the statement “If we have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of fishmongers and fishermen”, we’d have had quite a different view of 17th-century science…

***

Photo of Wollaton Hall, September 2021, Brigitte Nerlich. Photo of Willoughby the dog, with permission. Painting of Francis Willughby by Gerard Soest between 1657 and 1660 (Public Domain). Image of the frontispiece and title page of De Historia Piscium, Francis Willughby, Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0. Picture of young fisherman by Cornelis Bloemaert (II), print maker, Noord-Nederlands (1603–1692) (Public Domain)

Absolutely great! I love connections between personal history and the history of science, also between different parts of that history.

I am glad you like it!