June 19, 2020, by Brigitte Nerlich

Expertise: A tale of two meanings

I have recently become confused by how people use the word ‘expertise’. I’ll first tell you a story about the meaning I am used to and then a story about the meaning I am not so used to and conclude by asking what to do about this concept.

‘Expertise’ in ordinary language use

Staff at the School of Sociology and Social Policy where I ‘work’, were recently sent an email asking them to update their ‘areas of expertise’. This happens at a regular basis so that people interested in a doing a PhD know who could supervise them, for journalists to find the right people to speak to and for policy makers to find experts to help them.

Just for fun, let’s imagine a university where academics have a wide range of expertise, from pre-Babylonian musicology, to post-diluvial hydrodynamics, to the iconography of unicorns and the ecology of dragons. The latter type of expertise would allow scientists to distinguish between dragons, wyverns and lindworms for example, which is a surely a fantastic skill to have in these apocalyptic times.

I was dreaming about all this after first reading a twitter conversation initiated by Dorothy Bishop and then reading a 1976 article on the ecology of dragons, published in the journal Nature by Robert May, former President of the Royal Society, who died this year … (followed by an article in 2015 on the effects of climate change on dragons, called ‘Here be dragons’)…. I was also reading an obituary about a female mathematician, Ann Mitchell, who had been involved in Bletchley Park.

As everybody knows, during the second world war, experts in Germany had built the enigma machine, while experts in the UK were needed to decipher the messages it produced. These code-breakers came from mathematics to cryptography, to linguistics/philology, to ancient history, to chess, to philately, to classics, to logic, to engineering… and much more. Experts in all these ‘areas of expertise’ helped decipher the enigma messages.

This is what I always understood the words experts and expertise to mean. People who are really good at something or other in a specific area of knowledge and/or practice, including science in its broadest sense.

When looking at recent discussions about experts and expertise, it became obvious to me that I was not quite au fait with the current meaning of expertise though.

‘Expertise’ in the OED

So, I first looked up ‘expertise’ in the Oxford English Dictionary, which defined it as “(a) Expert opinion or knowledge, often obtained through the action of submitting a matter to, and its consideration by, experts; an expert’s appraisal, valuation, or report. (b) The quality or state of being expert; skill or expertness in a particular branch of study or sport.” I realised that I had focused on (b) and forgotten about (a). So what about (a)?

‘Expertise’ as a jargon term

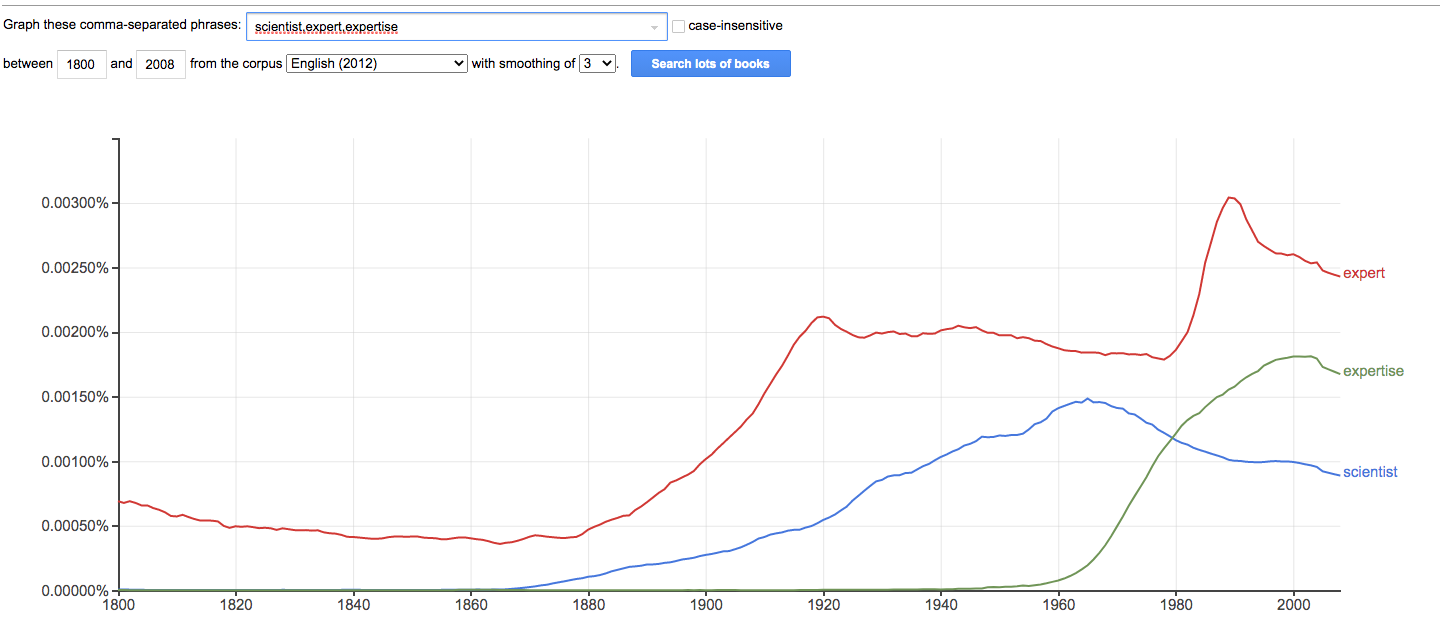

I then saw a recent tweet by Massimiliano Simons, a philosopher of science, where he drew quite a strict distinction between science and expertise and said the “latter is about policy: requires clearcut yes/no decisions on short term (vs endless, indecisiveness as acceptable)”. I had, of course, come across this distinction before, but never really thought more deeply about it. Now I began to wonder. I asked Massimiliano where this distinction came from and he gave a very helpful answer. This contained a reference to a book on the crisis of expertise by Gil Eyal and a graph from that book. That graph is very interesting and corresponds to a graph I had seen on Google when looking up the meaning of expertise.

Eyal’s graph is derived from Google Ngram viewer based on Google books and it shows that the word ‘expertise’ lay dormant for a long time and then quite suddenly started to be used with increasing frequency after the 1960s. As Massimiliano has pointed out in his tweet: “Expertise is a very recent term”. He also said that it “came into being to capture the contemporary use of science for policy (and the institutionalisation of that process).” We’ll get back to that.

To reproduce Eyal’s graph (in her book on p. 13), I experimented with NGram viewer and, as you can see, ‘expertise’ rose to prominence after the Second World War, while ‘expert’ chugged along more sedately, as well as ‘scientist’, which I added to the list, while I left out ‘profession’. ‘Expert’ had a little surge in the 1990s, probably because of rising interest in expert systems.

When I looked at some of the books that brought about this sudden uptick in use of the word ‘expertise’, I concluded that we seem to be dealing with a post-war expansion of use in specific domains (administration, regulation, judicial contexts) accompanied by a narrowing of meaning to, perhaps, ‘ability to provide an expert assessment or report’ – related to meaning (a) in the OED. Eyal speculates (and you have to read his book to get the whole story) that expertise rose in use because at that time it became necessary and useful to distinguish between experts and those who are not, while beforehand that seemed to be more self-evident.

Now, forty years after the concept emerged, a new wave started and that was a wave of studies studying expertise. This wave began, I think around the turn of the millennium with a famous 2002 article by Harry Collins and Robert Evans entitled “The Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience”. And again twenty years after that we have Eyal’s Crisis of Expertise, a book on The Philosophy of Expertise, another on The Death of Expertise and, of course, also the work on this topic by my colleague Reiner Grundmann.

To summarise all that work would take us too far. Let us just say with Torbjørn Gundersen (who wrote a very interesting article about the roles of scientist and expert) that many STS scholars would probably say: “Whereas the aim of scientific research is typically to produce new knowledge through the use of scientific method for evaluation and dissemination in internal settings, the aim of the expert is to provide policymakers and the public with relevant and applicable knowledge that can premise political reasoning and deliberation.” In this view (which is only one of many, as stressed by Gundersen), the role of scientists as researchers (contributing to knowledge production) is separated from the role of scientists as experts (contributing to policy making).

That chimes with what I found in a book symposium about Eyal’s book: “For Eyal, expertise is something that takes place at the intersection of science and action, and is fundamentally a problem of the state.”

‘Expertise’ (and ‘experts’) in the wild: Here be dragons

Having now established that there are two meanings of expertise that don’t really overlap, namely the ordinary language one and the STS language one, I looked back at that famous quote from Michael Gove where he said (in March 2016) that the British people had enough of experts. The distinction between the two meanings of expertise makes it easier to understand what he was saying. I think he was using the jargon term ‘expert’ to refer to all sorts of ‘elitist’ government advisors, including the Lord High Chancellor (see video clip), but not scientists as such.

Then I came across another quote, this time only understandable in the context of Covid-19 not Brexit and against the backdrop of the Gove quote. Gary Lineker had observed that yet again (June 2020) a politician had taken the daily press conference about the pandemic without advisors being present. He tweeted: “Seems the scientists are going the way of experts….to that silent place far away from government.” So, Lineker seems to think that the Chief Scientific Advisor and the Chief Medical Advisor (and other advisors) are ‘scientists’ not experts, although according to the policy jargon definition of experts they should be called experts not scientists, as they are scientific advisors.

To come back to the beginning: Let’s imagine academics who can distinguish expertly between a dragon, a wyvern and a lindworm. In the ordinary language view, they would be experts and work within an ‘area of expertise’, but in the STS jargon view they would not be experts and would not have expertise because their (scientific) knowledge and understanding is not (yet) policy-relevant and cannot contribute to policy making. That would be a bit weird to me – but perhaps I am just confused.

It seems that in the wild the distinctions drawn by experts in expertise between scientists and experts and between science and expertise are difficult to uphold … I wonder what this means for public understanding of science and expertise and for public trust or distrust in scientists and experts?

PS. Somebody who is not confused about experts and expertise is Arnold Schwarzenegger. One year after I mused about experts, in August 2021, he said something rather profound: “I always say you should know your strengths and listen to the experts. If you want to learn about building biceps, listen to me, because I’ve spent my life studying how to get the perfect peak and I have been called the greatest bodybuilder of all time. We all have different specialities.” And: “It takes strength to admit you don’t know everything. Weakness is thinking you don’t need expert advice and only listening to sources that confirm what you want to believe.”

Image: Pixabay

Very interesting, but there’s a longer history here. Look at the growth in use of ‘experts’ c1880-1920. That reflects a significant growth in government experts, which was bound up with the changing roles, characteristics and relationships of science and the state. While ngram suggests the word ‘expertise’ was not widely used at the time, these experts clearly possessed something that distinguished them from other individuals. My account of government vets in this period revealed that ‘rather than a self-evident attribute that justified particular appointments and enabled them to fulfil their duties, expertise … [was] a continually evolving phenomenon, moulded by policy challenges, professional ambitions and the administrative setting.’ (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/007327531305100404)

So nice to hear from an expert on experts! I was intrigued by the difference between the curves followed by the words ‘expert’ and ‘expertise’ and I am glad to learn more about the reasons why and how the two words evolved together but apart over time!