February 1, 2019, by Brigitte Nerlich

Reimaging AMR – beyond the military metaphor

Last week the UK government launched yet another ‘action plan‘ on dealing with the rise of antimicrobial resistance or better ‘drug resistant infections‘, that is infection that no longer respond to antibiotics because the bacteria that cause the infections have developed resistance to the drugs used to eliminate them…….

This is a guest post by Sally Zacharias. She is an educational linguist and applied linguist with a special interest in cognitive linguistics and works at the School of Education at the University of Glasgow.

***

This is a short report on the afternoon event ‘Reimaging AMR – beyond the military metaphor’ held on 10th January 2019 at the University of Edinburgh and organised by BEYOND RESISTANCE*, founded by Iona Walker, in association with Medical Centre of Medical Anthropology, Edinburgh Infectious Diseases, Atelier: An Arts and Social Sciences Network.

One of the purposes behind the event was for both medical and social scientists as well as leading artists to come together to discuss the prevalent use of the military metaphor to frame our relationship with the microbial world, and whether alternative metaphors would lead to a beneficial change in the way public health campaigns are structured.

Metaphors are powerful: they shape the way we think, communicate and act in the world. This applies also to how we conceptualise our relationship with disease and how we in the western world treat it. Construing this relationship as a ‘fight’ in which our ‘enemy’ is the microbe, positions the health profession as those ‘waging a war’ against it. But is the microbe really our enemy? As someone said at the event, microbes were around long before us and will be around for a long time after we are gone; they are very much part of us and when waging a war against them we are also waging a war against ourselves.

Speculations on where the metaphor originally came from were also made. Alexander Flemming discovered penicillin between the two World Wars – did this influence how people chose to talk about disease at the time? In our present political climate, we frame other high-profile scenarios such as climate change and Brexit as crises – ones that force us to behave as if we are in a war situation. However, will we soon tire of this metaphor and give up hope if we see we are a long way from winning the battle?

Ethical implications of the metaphor were also discussed. Certain behaviours are only acceptable in war situations (e.g. killing). Wars have winners and losers – who then on a global scale will win and lose this war?

Art and alternatives

Framing our relationship with microbes as a war prevents us from considering alternative perspectives. The ubiquity of the metaphor meant we struggled to think of alternatives, and it was only by taking different perspectives did new ones begin to emerge. In the evening, Sarah Craske an award-winning artist based in Basel and leading curator of Basel’s pharmaceutical museum gave a fascinating talk on how disease shaped Basel to be the city it is today.

By viewing our relationship with the microbial world through a wider time span a new language began to emerge. She spoke about how new diseases emerged and evolved and of the ebb and flow of disease and the city’s growing response to it. This was represented in her artwork too, which depicted maps of the city showing outbreaks of disease through time. You can read more about her work here.

Questions, questions

Questions were asked on whether different languages and cultures use different metaphors to frame our relationship we have with the microbial world. Are different aspects foregrounded? Scientific English with its heavy use of noun phrases tends to place an emphasis on the objects under study rather than on the relationships between those objects – does this have implications too on how AMR is communicated across the globe, especially with English being the dominant language of science?

I left the event with many unanswered questions that will no doubt guide my thinking on this topic until the network meet again: To what extent should the military metaphor be used to frame the way we think about our relationship with the microbial world? What are the constraints and affordances of using this metaphor? And if it does bring benefits, how should it be used, in what contexts and with whom? And, finally, what are the alternatives?

A few reading suggestions on war metaphors and antimicrobial resistance (by Brigitte)

Larson, B. M., Nerlich, B., & Wallis, P. (2005). Metaphors and biorisks: The war on infectious diseases and invasive species. Science communication, 26(3), 243-268.

McMichael, T. (2002). Book Review: “Secret agents: The menace of emerging infections (Books: public health: Fine battlefield reporting, but it’s time to stop the war metaphor).” Science, vol. 295, no. 5559, p. 1469.

Nerlich, B., & James, R. (2009). “The post-antibiotic apocalypse” and the “war on superbugs”: Catastrophe discourse in microbiology, its rhetorical form and political function. Public Understanding of Science, 18(5), 574-590.

Nerlich, B. (2012). Biomilitarism and nanomedicine: Evil metaphors for the good of human health. Covalence.

Nerlich, B. (2016). Blog post on Infectious futures and the apocalypse metaphor…. here

Flusberg, S. J., Matlock, T., & Thibodeau, P.H. (2018). War metaphors in public discourse. Metaphor and Symbol, 33(1), 1-18.

and there is probably more stuff out there…

There is also more antimicrobial art to be explored, here (Microbes and metaphors) and here (Bioart and bacteria)

and again, there is probably more out there….

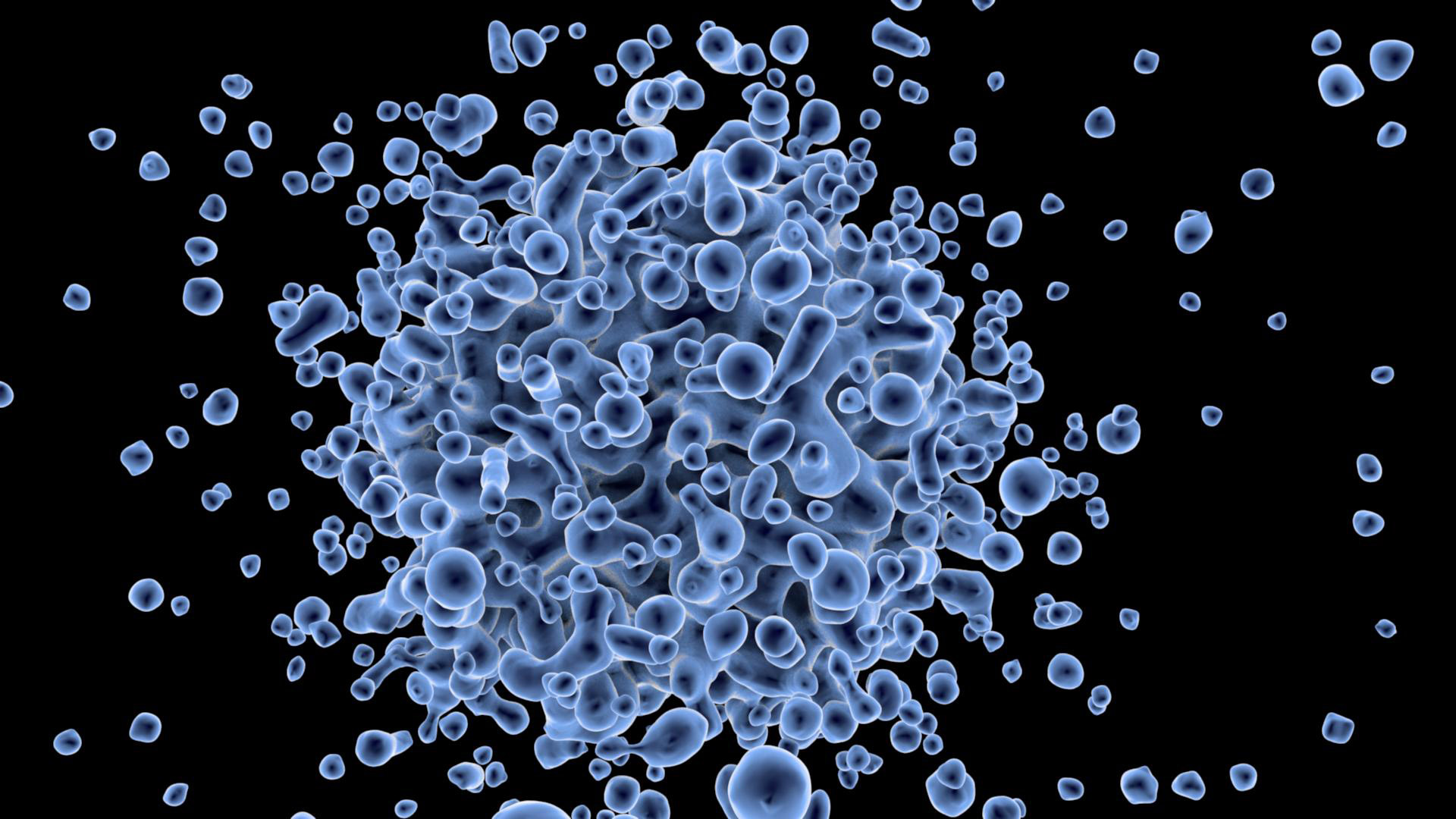

Image: Public domain

It’s been a while since I read it, and it is in German so not accessible to all, but Marianne Haenseler’s book _Metaphern unter dem Mikroskop: die epistemische Rolle von Metaphorik in den Wissenschaften und in Robert Kochs Bakteriologie_ (Zurich: Chronos, 2009) has a very good discussion of microbe and disease metaphors in the 19th and early 20th century.

Thank you!! We’ll look into that asap!

A great lead – thank you!