January 29, 2018, by Brigitte Nerlich

Framing cloning: Dolly and the monkeys

In 1999, three years after Dolly the sheep was born, we published an article on the way that cloning was then framed in the public sphere (see also Holliman, 2004). The cloning of two macaque monkeys by Chinese researchers (Cell, 2018), more than two decades after the cloning of Dolly might be a good opportunity to look again at how cloning is being framed in the public sphere today and to see whether anything has changed or not.

That would however involve a lot of work, work that goes well beyond a single blog post. In this post I will only highlight some initial thoughts that struck me when looking at the old article and at some of the news that’s been generated by Hua Hua and Zhong Zhong, the cloned monkeys. I shall not go into the science and ethics of this achievement, as others have done this much better than I ever can.

Reading through the old article again, several things struck me.

Familiarising through fiction and fact

When framing the cloning of Dolly the sheep, scientists and journalists had to contextualise this event somehow; they had to use something familiar to talk about something unfamiliar. To do this, they anchored the cloning of Dolly to ‘common knowledge’ about cloning. This itself was, at the time, rooted in some early cloning science, some early ethical reflections, but mainly in science fiction.

As David Rorvik wrote in his controversial book In his Image: The Cloning of Man (1978): “Like a red flag, cloning would alert” (and in fact it did and still does) “the world to the awesome possibilities that loomed ahead and thus serve as a catalyst for public participation in life and death decisions that might otherwise be left by default to the scientists.” A nice description of ‘Responsible Research and Innovation avant la lettre (although the book itself wasn’t!).

Today’s journalists, science writers and bloggers, writing about the cloned monkeys, can make this now not so unfamiliar event more familiar by not only referring to little known science and ethics as well as well-known fiction, but also by framing it with reference to Dolly the sheep. This cloned sheep has become a familiar icon of cloning, carrying a lot of conceptual baggage in terms of science and ethics, fears and fantasies. It would be fascinating to see how Dolly is used rather than (or in conjunction with) science fiction to engage with people anew with cloning.

Framing animal and human cloning

In one of the first paragraphs of the old article, we refer to a then hot-off-the-press MA thesis by Alan Hodgson entitled “Undressing Dolly: A clone’s 12 months gestation period in the UK press” (1998) (but we don’t go on to quote from this thesis, as I’ll do now). In his synopsis, Hodgson writes: “The most striking facet of the UK press ‘agenda-framing’ in light of sheep Dolly is that immediately the press extrapolated the result of ‘cloning’ one sheep to the potential applicability of the technology to humans.” (p. 5)

This is exactly what’s happening again now, but more forcefully, as we are dealing with the cloning of primates. However, since Dolly, lots of rules and regulations have been established that prohibit human cloning. It would be interesting to see how these are referenced in the news articles.

Hodgson goes on to point out: “The framing therefore quickly centred on four initial questions, ‘Can the technology be used on humans?’, ‘Will it happen?’, ‘In what circumstances?’ and concomitantly ‘Should it happen?” (p. 5). Again, that’s what’s happening now, it seems. A more thorough analysis of the news could try to ascertain whether these questions are still being asked, or whether other questions have emerged.

Hype and collusion

Then Hodgson makes a rather astute observation: “… commentators became imbricated not only in the process of actually weighing the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of human cloning but also in constructing a social need for it.” (p. 5) At this point I should really stop writing this blog post! But, of course, I won’t.

The issue of colluding in hype is however something that we commentators, including social scientists, should really think about. Instead of constructing a social need for looking at the threats of human cloning, commentators should perhaps distance themselves from such constructions, as some are already doing.

When looking at our old article, I found an interesting paragraph: “If policy makers had appreciated just how much a long-standing tradition of fiction relating to cloning and genetic engineering had prepared the ground for the discussion of the facts of the genetic revolution, a more self-conscious rhetorical distancing of genetic science from genetic fiction might have made possible a more open public debate.” This is something that people writing about the cloned monkeys might also want to think about with relation to what some call ‘ethics hype’.

Questioning assumptions

Two decades after Dolly knowledge and understanding of cloning is still sparse and probably still largely dependent on fiction, conventional metaphors and unquestioned assumptions. Just take a look at this expression of caution: “But even if it were safe, many researchers say there are many other reasons to never try. ‘Cloning one individual in the image of another really sort of demeans the significance of us as individuals,’ says Dr. George Daley, dean of the Harvard Medical School. ‘There’s a certain sort of gut sense that it violates sort of natural norms.’”

This gut sense seems to overlook that there are millions of clones, namely identical twins or even triplets etc., that already roam this planet. I am one of them and I have never felt that my dignity was threatened by my clone! (I should point out that clones which result from egg-splitting are not technically the same as clones that result from somatic cell nuclear transfer, but that does not distract from the point I want to make about dignity)

And, of course, as people said over and over after Dolly was born: the technical and physiological hurdles are still too great to successfully clone humans; there is no real need given the availability of other reproductive technologies, etc. As some have stressed, we are really not dealing with a “Never Let Me Go scenario – the science fiction novel in which human clones are created for spare organs”, a scenario so widely discussed 20 years ago. As a New Scientist ‘Leader’ says: “The ethical debate is very much alive, but clones are not where the action is – at least for now.” I’ll check back in another 20 years….

Some initial impressions of news coverage

To get a rough, very rough, impression of the media coverage of this new cloning event I went to the data base Lexis Nexis. I searched for ‘clone’ Or ‘cloning’ and checked out All English Language News (between 24 and 26 January). I got 738 hits (on a high similarity setting). I then searched within these results for ‘human’ and got 440 hits. I did the same for ‘Dolly’ and got 393 hits. So quite a substantial number of articles discussed the very distant possibility of human cloning and quite a chunk of articles used Dolly as a reference point. With respect to the former the articles are not much different to articles written when Dolly was cloned; with relation the latter they are, of course, quite different.

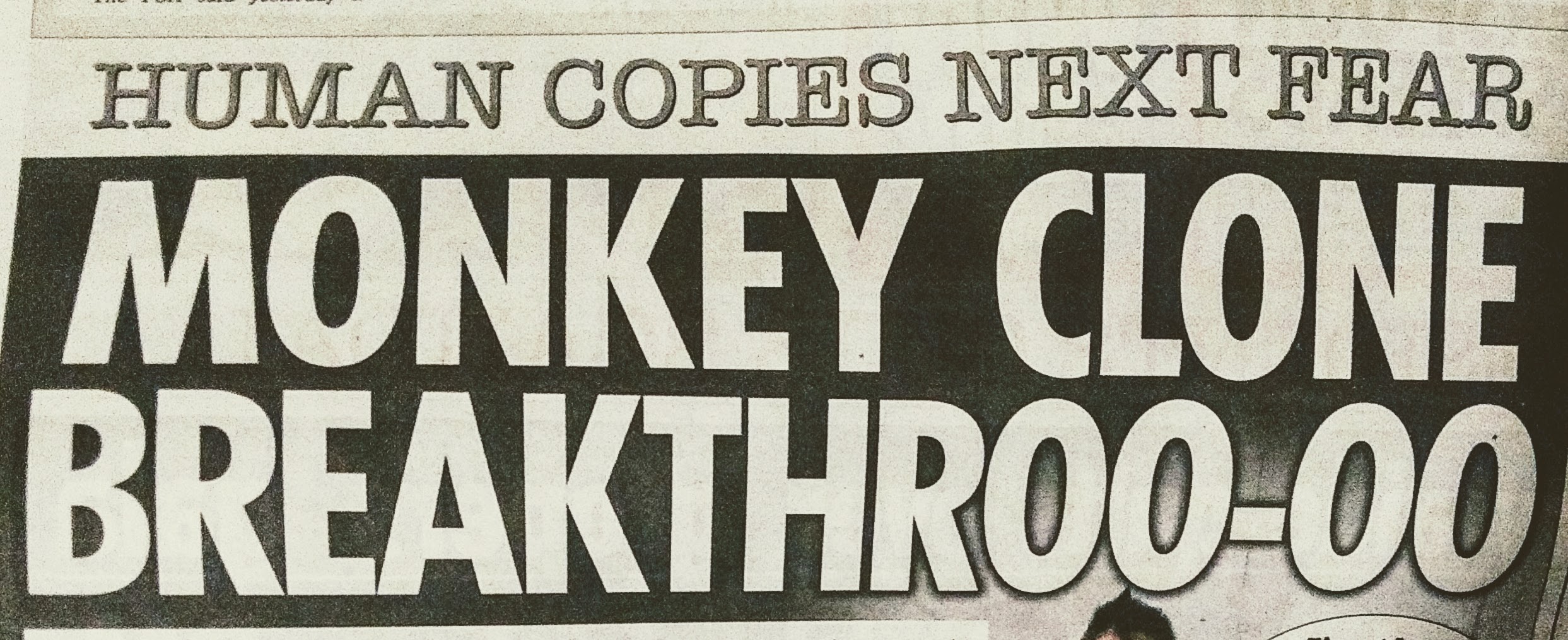

There were quite a few headlines playing with words and connotations relating to monkeys, such as this Sun headline for example:

What about science fiction? Searching for ‘science fiction’ gave me 25 hits. Not a lot! And no results for ‘scifi’. ‘Gattaca’ was, surprisingly, not used as a reference point and ‘Brave New World’ only twice, same as ‘Frankenstein’ (however, ‘Frankenscience’ makes its appearance six times, based on a quote from PETA). The 1978 cloning film ‘Boys from Brazil’, which made quite an impression on people discussing Dolly at the time, was mentioned twice. There is one reference to ‘opening Pandora’s box’, but ‘slippery slope’ is used 39 times.

What about novels written after Dolly, such as Never Let Me Go, mentioned above, a 2005 dystopian science fiction novel by Nobel Prize-winning British author Kazuo Ishiguro? This is referenced 15 times. Still not an awful lot.

Skimming the headlines, it seems that most news items report the cloning as a scientific fact. Quite a few voice ethical concerns and fears about human cloning. But there are also some that sound more positive and focus on this advance opening up new avenues for research or offering hope in finding treatments for degenerative diseases.

Overall then, science fiction seems to be backgrounded 20 years after Dolly while science seems to be foregrounded. However, the questions asked still seem to be very much the same as two decades ago. More research needed! Anybody up for it?

Images: All images of the monkeys were copyright protected. So I couldn’t include any. Dolly: Wikimedia Commons: Image: Wikimedia Commons: Pvasiliadis, ‘Everybody is Dolly’ graffiti at Thessaloniki, Ermou Str., 19 January, 2010. Sun Headline: photo, 26 January, 2018.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply