January 15, 2017, by Brigitte Nerlich

‘An Inconvenient Truth’: Exploring the dynamics of making climate change public

Warren Pearce and I wrote a guest post for And Then There is Physics. I am reposting it here with permission.

***

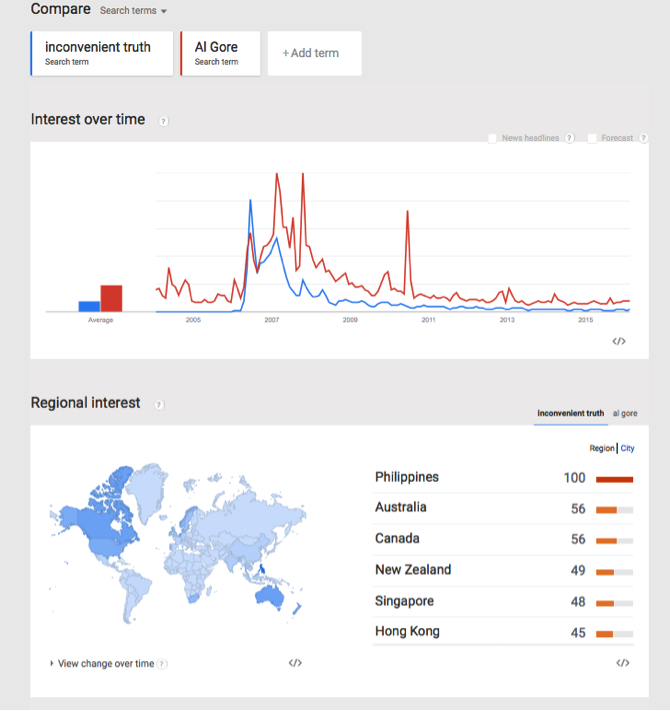

In 2006, Al Gore’s climate change documentary ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ (AIT) was released, garnering substantial public attention. In a forthcoming chapter of a book on Science and the Politics of Openness (part of the Leverhulme Trust funded Making Science Public programme), we discuss the film as an example of taking climate change expertise out of the pages of science journals and into the public sphere.

While the purpose of the documentary was to persuade its audience of the consensual truth imparted by climate science experts, its effect was to become a lightning rod for dissent, critique and debate of that expertise. It became a touchstone for consent and dissent, action and reaction.

In our chapter we use some aspects of social representations theory to show how the film fostered the emergence of a (sought-after) dominant or ‘hegemonic’ social representation of climate change, while also triggering a (not so sought-after) ‘polemical’ social representation. We also observe how the film created both a public and a counter-public.

We use aspects of political theory to discuss our findings, mainly taken from the work of John Dewey, as discussed by the political theorist Mark Brown. In around 1900 Dewey started to think about the effects that increasing professionalization and specialisation of expertise could have on what he called the popularisation of knowledge. His thoughts still resonate today. Dewey was worried that these trends would make knowledge less accessible to the public, but more importantly he feared that if expert knowledge was no longer integrated in society, this would spell dangers for democracy.

From this perspective one can see AIT as a success, both as a cultural event and as a means of bringing public meaning to climate change and momentum to climate change mitigation. AIT’s combination of scientific ideas with personal stories and political activism echoes Dewey’s call for ‘bare ideas’ to have ‘imaginative content and emotional appeal’ in order to be effective (Dewey, 1989: 115). AIT also takes seriously Dewey’s notion that scientific expertise is a social product rather than the result of individual scientific brilliance and that science communication marks the return of knowledge to its rightful owners: the public. Indeed, AIT takes this one step further by seeking to empower its audience to gain the expertise to go out and disseminate locally.

Yet while Dewey points to the seeds of AIT’s success, he also shows how the successful communication of scientific knowledge and its social consequences brings more public scrutiny to bear on expertise. AIT does not only fill information deficits or knowledge deficits. Individuals are not merely passive recipients of (dominant or hegemonic) representations; they actively contribute to the construction of new representations in response. Some of these individuals assumed a critical view of AIT and Gore and began to construct a polemical counter-representation that challenged the film’s scientific credentials and its main message. This happened especially on blogs critical of mainstream climate science. A struggle ensued not only over AIT’s scientific accuracy (‘bare ideas’) but also about the films dominant personality, Al Gore as public expert and the financial and political context of his ‘enterprise’ (the social and emotional context). Bare ideas never occur in a vacuum and cannot be transmitted in a vacuum.

In its mix of the scientific, personal and political, AIT is perhaps best thought of as an ambitious, if flawed, experiment in science communication and in making climate change meaningful. It did so, whether consciously or not, by politicising climate change and reintroducing the human into previously apolitical representations of climate change. While it is now time for politics, not science, to bear the load of dealing with climate change, we note that one effect of AIT was to turn climate science into ‘Al Gore’s science’, closely tied to a narrow range of policy options that were anathema to US conservatives. This poses problems for both science and politics.

Both the success and failure of AIT show that while it is important to get (expert) knowledge and information out there, that information is always part of a wider context; and once ‘out there’, it will always take on a life of its own, which is difficult to anticipate and control. Knowledge is produced by people (with political and financial interests) for people (with political and financial interests). As Dewey said, to be effective, ‘bare ideas’ need to have ‘imaginative content and emotional appeal’.

With AIT’s success in bringing social context to scientific content came inevitable contestation. Scientists and experts have to be prepared for this.

Image: Google Trends, accessed end of 2015

PS: March 2020: There is now a great podcast on AIT and Documentaries, Performance and RISK by Alamo Pictures, with James Lyons, University of Exeter

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply