September 18, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

Zika, poems and people

Friday morning (16 September) two things happened. I was preparing for a meeting with colleagues (Sarah Hartley and Barbara Ribeiro) to discuss findings from a project examining Brazilian media coverage of the Zika virus epidemic.* At the same time I got an email asking me to contribute something to a volume on the 2009 swine flu pandemic. I therefore quickly looked into an old folder on my computer called ‘swine flu’ and came across a file with a list of hyperlinks to ‘swine flu poems’ which I had started to collect at the time, but never used.

This made me think: What if there were Zika poems out there!? So I googled and, lo and behold, there actually are some Zika poems – but why did I want to look at them? Why am I interested in poems written during epidemics or pandemics, such as the current outbreak of Zika?

Poems and epidemics

I first started to think about poems and infectious diseases when I directed a project dealing with the social and cultural impacts of the 2001 outbreak of foot and mouth disease in the UK. In that project we mainly wanted to interview farmers and others who had been affected by the outbreak. While carrying out our research we found that alongside the outbreak of a disease there was a veritable outbreak of poetry. In the end we collected more than 450 poems written by farmers, vets, children, teachers, poets, scientists and many more. They provided a way of ‘listening’ to people in the most unobtrusive way possible. We found short poems, such as this 2002 school-yard rhyme (“Mary had a little lamb; Its mouth was full of blisters; And now it’s lying in a ditch; With all its brothers and sisters”), and long poems, such as the one entitled ‘No Entry’, by the then poet laureate, Andrew Motion – and everything in between.

We subsequently argued that such poems, alongside novels, plays, photographs, paintings and so on, provide unique insights into the ways people dealt with the outbreak, insights that could not be extracted from surveys, interviews or focus groups; insights that, we believe, could provide policy makers with useful information about public understanding and public coping, both with the outbreak and the impacts of their policies. ‘Findings’ from the analysis of such poems could, in an ideal world, feed back into preparing more human and animal-friendly policies for future disease outbreaks.

Zika poems and poemas

I can’t see the same outbreak of poetry happening for the Zika virus epidemic as we saw for foot and mouth disease – but I haven’t looked close enough, especially in Brazil. I found a few poems written in English and a few written in Portuguese, but I haven’t checked other languages. Most poems were written in 2016 when Zika suddenly became a public health issue around the world.

Zika virus disease is transmitted through insects bites from mosquitoes, such as Aedes aegypti. However, it became clear over time that the virus can also be transmitted sexually and from mother to foetus and can lead to microcephaly in babies and other neurological disorders in adults. The virus has now spread widely around the world, but has affected Brazil particularly badly.

Some of the English poems I found approached Zika from a religious perspective (and mention GM mosquitoes); one spoke about the fear of travelling to Zika affected countries and a shrinking world, a fear that another described from the point of view of the virus itself (aware of the media circus surrounding its spread); some dealt with the science of Zika and finding solutions. One poem detailed the medical problems associated with the virus, especially the issue of microcephaly in babies born to mothers that had been infected with the Zika virus (this poem was written by somebody in Malaysia who feared that Zika would arrive there too). There was also a poem from Florida where Zika has emerged recently, dealing with the issue of the mosquitoes breeding grounds (pools of standing water):

Sticky hot air finds deft dragonflies

adrift in the live oak hammock

in search of mosquitoes hatched

in yesterday’s torrential downpour.

Another poem spoke about the Brazilian carnival and the Olympics, alluding to the complex political background in which the epidemic plays out in Brazil, especially the impeachment of the then President Dilma Rousseff who had declared ‘war’ on Zika, but also the economic recession.

By contrast with the poems written in English, the poems written in Portuguese focused much more directly and powerfully on fear and dismay. Zika is the described as the final straw in a cruel world. It is a dangerous monster, a poison and a plague, even the devil. The Zika virus is terrifying, especially as it can affect the foetus. A Spanish language poem explores normal Zika symptoms, but also the emerging threat to the fetus.

In general, the threat posed by the Zika virus is described as new, but the poems also talk about it in a cultural context where people have experience of regular outbreaks of dengue fever and chikungunya – diseases carried by the same insects that carry Zika. Indeed, in our media analysis we found what one might call a disease discourse ‘triplet’, as Brazilian newspapers often talked about Zika, dengue and chikungunya in one breath.

Singing Zika

One video of an old man singing a poem is especially powerful. Here is Barbara’s quick translation of what the old man signs:

My friend, be careful, be careful so you won’t be bitten

My friend, listen to me as I shout, I’m talking about the mosquito’s bite

It’s the Epsus egipsius*, so small that no one can see it

But when it bites someone

It’s a real problem

Because then it comes Dengue, haemorrhagic Dengue, Chikungunya and the Zikuvia*

Oh my God, what an agony!

It’s even worse when it bites pregnant women

And children are born with microcephaly

The city council has joined the fight

And the governor as well

Even the President has joined the group with the civil servants

But the mosquito is “xaroposo” (syrupy?)

And is calling everyone a fool

Even the army

Also joined the war

Oh my God, what is happening

It even looks the seven plagues of Egypt

The whole world fighting against the mosquito

But is the mosquito who is winning, but is the mosquito who is winning

(*he misspells it a few times, probably to make it rhyme)

Our initial analysis of media reporting of the Zika outbreak in Brazil found that the war metaphor, also used in this poem or song, was a dominant way of framing ‘disease management’. We also found metaphors which echo some of those used in this song and in the other poems. Zika is represented as a bandit, a hanger-on, a mosquito of fear, a ghost, bad luck/urucubaca, supreme suffering, chaos, a tragedy, a pain, a terrible and great mystery…. All this would lend itself to some future comparative analysis of ‘poetic’ framings of a wide variety of infectious disease outbreaks.

Conclusion

In this post I dipped my toes into some cultural manifestations of people coping with the Zika virus in Brazil, what some social psychologist may call ‘symbolic coping‘. After the outbreak of poetry during the foot and mouth disease epidemic we argued that policy makers should listen not only to (invited) people gathered in focus groups for example, but also to ‘uninvited‘ people. Reading and analysing poems may give social scientists a unique opportunity to hear the voices of some actors and their lived experience which are rarely included in political debates and decision-making. Poems provide rich sources of ‘data’ which normally overlooked in policy making and even public participation processes. They are there to be used.

Suggested readings

Nerlich, B., Hamilton, C. and Rowe, V. (2002). Conceptualising foot and mouth disease: The socio-cultural role of metaphors, frames and narratives. metaphorik.de

Larson, B., Nerlich, B. and Wallis, P. (2005). Metaphors and biorisks: The war on infectious diseases and invasive species. Science Communication 26(3), 1-26.

Döring, M., B. Nerlich (2007). An outbreak of poetry: Mapping cultural responses to foot and mouth disease in the UK, 2001, in: Fill, A., Penz, H. (eds.). Sustaining language: Essays in Applied Ecolinguistics. Vienna: LIT Verlag, 181-202.

Döring, M. and Nerlich, B. (2009). The social and cultural impact of Foot and Mouth Disease in the UK in 2001: Experiences and analyses. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Nerlich, B. (2009). ‘As if Goya was on hand as a marksman’: Foot and mouth disease as a rhetorical and cultural phenomenon: In: Culture, Rhetoric and the Vicissitudes of Life, ed. by M. Carrithers. New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 87-106.

Nerlich, B., McLeod, C., Burgess, S. (2016). Frankenflies sent to defeat monster mosi: Zika in the English press. Blog post. PLOS Synbio Community Blog.

*The project is funded the Governance and Public Policy Research Priority Area at the University of Nottingham (data were collected by Izabel Rigo Portocarrero).

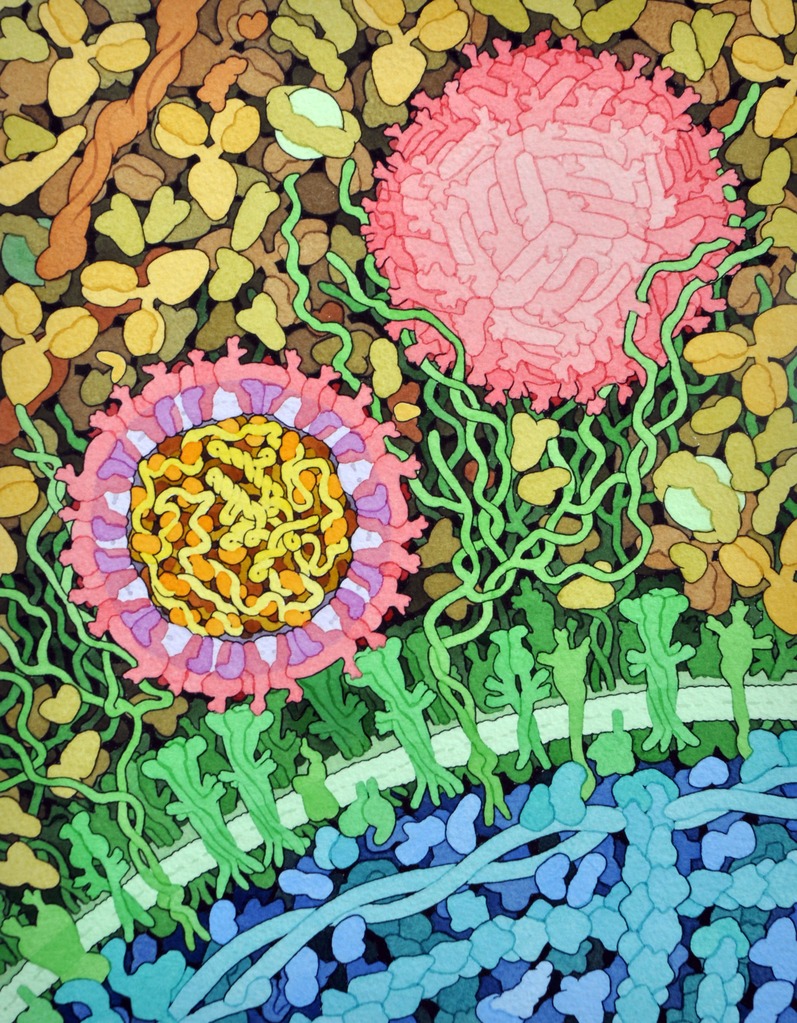

Image: Space-fill drawing of the outside of one Zika virus particle, and a cross-section through another as it interacts with a cell. The outer shell of viral capsid proteins are in pink, the membrane layer with purple proteins, and the RNA genome inside the virus in yellow. The cell-surface receptor proteins are in green, the cytoskeleton in blue, and blood plasma proteins in gold. Drawn by David Goodsell. (1 June 2016)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply