March 30, 2016, by Warren Pearce

Reviewing the evidence on transparency in science: a response to Lewandowsky & Bishop.

Co-authors: Warren Pearce, Sarah Hartley & Brigitte Nerlich.

In January, Nature published a Comment piece by Lewandowsky and Bishop entitled “Don’t let transparency damage science“. The authors argued that some of the “measures that can improve science — shared data, post-publication peer review and public engagement on social media — can be turned against scientists”. Following this observation, they propose a series of ‘red flags’ that may be raised about researchers or their critics within a number of categories. The piece caused some consternation in the science blogosphere and here at Making Science Public, leading us to pen a brief response that Nature published in February. Here, we expand a little on the themes of our correspondence.

The danger of simplified dichotomies

Social problems are complex, often bewilderingly so. A key task for social scientists is to make sense of this complexity. As the aphorism (not quotation!) says: “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler”. Unfortunately, Lewandowsky and Bishop do over-simplify the complex issues in play when thinking about transparency in science, portraying them as dichotomies that pit researchers against their critics. What’s worse is that this over-simplification appears in the pages of Nature, science’s most high-profile forum. This dangerously inflames tensions in controversial areas of public science and stymies efforts to break deadlocks. This was noticeable in ‘below the line’ comments on Nature, especially from chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) commentators. The authors expressed surprise at such reactions, but such a caricatured presentation of delicate issues was always likely to garner robust opposition.

The dangers of unsubstantiated claims

Lewandowsky and Bishop claim to have “identified ten red-flag areas”, but no evidence is provided as to how these were identified. For example, it is claimed that “hard-line opponents” to research on nuclear fallout, vaccination, CFS or GM organisms “have employed identical strategies” to opponents of climate change and tobacco control research. No evidence is supplied to support this view, which has the effect (intended or otherwise) of discrediting campaigners in these areas (only CFS researchers were represented at the Royal Society meeting that prompted the Nature piece and that one of us (Pearce) attended). Indeed, the cases are very different. For example, corporate interests play very different roles within the debates over climate change and GM organisms. It is imperative to focus on social contexts when trying to understand what drives some, but not all, of the criticisms levelled at scientists. Not doing so is especially troubling as there is social science evidence available that sheds light on these ‘red-flag’ issues, but which are ignored in the piece (see below for a list of further reading, short and long). Writing such an important piece in a journalistic style and making sweeping claims unsupported by evidence is dangerous, as it may inflame the debate still further. It is somewhat ironic that scientists who are also experts in science communication have seen fit to write a piece that is so cavalier with evidence, especially evidence about expertise.

Who is the expert?

Lewandowsky and Bishop present researchers and their critics operating outside of their area of training and/or expertise as worthy of a ‘red flag’. However, no consideration is given as to how such an ‘area’ might be delineated. As Harvey Graff explains in his recent book on interdisciplinarity, the exchange of ideas between different areas of knowledge has been central to the emergence of many of today’s established disciplines. Yet Lewandowsky and Bishop consider boundary transgressions to be rewarded with a red flag for researchers. A decade ago, Sheila Jasanoff succinctly summarised the problem:

“Difficulties in securing responsible criticism are compounded when, as is often the case for public science, claims and data cut across disciplines, involve significant uncertainties or entail significant methodological innovations.”

So the fundamental question is who counts as an expert, and under what conditions? This is by no means self-explanatory. In the case of oophorectomies, for example, Stephen Turner shows (£) how online commenters provided an important check on the inflated rhetoric of medical experts who claimed that the process had no significant side effects. Blog posters who provided their own personal experiences were subsequently proved correct. This is not to say that we should always privilege online commenters over professional researchers. Rather, that they provide different types of expertise which should be included in controversial areas of public science.

Where are the public?

Unsurprisingly, but depressingly, there is a large hole in Lewandowsky & Bishop’s analysis where the public should be. There is no mention of what the public interest might be in raising ‘red flags’, and what role sections of the public can play in science. Close reading of the article reveals it to be really about science governance, an issue too important to be left to the research community alone. What the piece does demonstrate is that a broader public discussion about the role of scientific experts in society is needed. Lewandowsky & Bishop argue that science is vulnerable to abuse. We agree, and scientists should be subject to the same legal safeguards as any other members of society. However, attempting to delineate general (and to some extent off the cuff) rules for distinguishing legitimate and illegitimate criticism risks doing more harm than good, and can lead to further distancing science from the society it is supposed to serve. A more fruitful approach to addressing public doubts about science was proposed by David Demeritt in 2001 (writing about climate change but, we argue, more generally applicable):

“The proper response to public doubts is not to increase the public’s technical knowledge about and therefore belief in the scientific facts of global warming. Rather, it should be to increase public understanding of and therefore trust in the social process through which those facts are scientifically determined. Science does not offer the final word, and its public authority should not be based on the myth that it does, because such an understanding of science ignores the ongoing process of organized skepticism that is, in fact, the secret of its epistemic success. Instead scientific knowledge should be presented more conditionally as the best that we can do for the moment. Though perhaps less authoritative, such a reflexive understanding of science in the making provides an answer to the climate skeptics and their attempts to refute global warming as merely a social construction.”

Lewandowsky and Bishop pinpoint some pitfalls in the societal process of science, but a cavalier attitude to evidence has inadvertently reinforced a caricatured image of this process.

Social scientists: up your game!

What is noticeable is how little these social sciences critiques have cut through to those in the natural sciences. To be clear, there is no excuse for ignoring the existing evidence base. However, we believe that social scientists must be more proactive in using that evidence base in order to lead the debate from a position of strength.

Further reading

Short reads:

Janz, N. (2016, January 29). Getting the idea of transparency all wrong. Political Science Replication.

Kiser, B. (2015, November 16). The undisciplinarian. A View from the Bridge. (an interview with Harvey Graff)

Murcott, T. (2012, July 11). Unreasonable doubt. Research Fortnight.

Nerlich, B. (2012, October 12). Making the invisible visible: On the meanings of transparency. Making Science Public.

Pearce, W. (2013, November 3). The Subterranean War on Science? A comment. Making Science Public.

Tamblyn, J. (2013, May 22). Bring on the yawns: Time to expose science’s ‘dirty little secret’. Making Science Public.

Hulme, M., & Ravetz, J. (2009, December 1). ‘Show Your Working’: What ‘ClimateGate’ means. BBC.

Long reads:

Graff, H. (2015). Undiscipling Knowledge: Interdisciplinarity in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Hess, D. J. (2010). To tell the truth: on scientific counterpublics. Public Understanding of Science, 20(5), 627–641.

Jasanoff, S. (2006). Transparency in public science: purposes, reasons, limits. Law and Contemporary Problems, 69(3), 21–45.

Stilgoe, J., Irwin, A., & Jones, K. (2006). The Received Wisdom: Opening up Expert Advice. London: Demos.

Turner, S. (2013). The blogosphere and its enemies: the case of oophorectomy. The Sociological Review, 61, 160–179. (*subscription required)

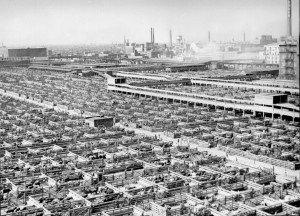

Image: Livestock Chicago 1947, Wikimedia Commons

Since I had written about the Lewandowsky and Bishop article, I wrote a post about your response.

https://andthentheresphysics.wordpress.com/2016/04/02/on-transparency/

It’s somewhat critical, but maybe I misunderstand some of what is being suggested.

My one direct question is what you mean by your final two sentences

What is your evidence base, and why should social scientists be aiming to lead the debate from a position of strength?

Sorry, I didn’t get an email about this comment, so didn’t see it until I read about it on your blog. I think Warren might be able to answer your last question. In the meantime I’ll try to say something about what we tried to say. I agree with L&B that transparency is important but that it also can be misused. Making people aware of how, when, where and by whom that misuse can occur is also important. Social scientists have been looking at all aspects of transparency and openness for some time. However, L&B did not refer to that long tradition of both support for transparency and of critique of the pitfalls of transparency. We thought that they could have used some of it to support their arguments with more evidence. They could also have used some of it to make their argument stronger, more nuanced and avoid some misunderstandings. Above all they could perhaps have avoided people reading their article in a dichotomous way as if it was setting up an image of us vs them. As things stand, you have Dr A on the one side and ‘the critics’ on the other. Could it not be that Dr A could also be ‘a critic’, etc.? There are many possible ways, a whole spectrum of ways, that ‘experts’ and ‘critics’ can interact (and exchange roles), collaborate, exchange data etc. Of course there are situations of harrassment and abuse, which should be strongly condemned, but it’s not as manichaen out there as the article makes it appear to be – perhaps unwittingly. We wanted to stress that beyond the experts and the critics there are many many interested people (I don’t like the word publics) who can constructivley contribute to scientific debates but who might not feel they can after reading this article. The article challenges those who misuse transparency. This is good. But it also seems to close the door on many people who might have been looking forward to a more open, participatory and public science that seems to be in the process of emerging. The article made make them retract their feelers and retreat into their shells.

I agree though that we could have ourselves used more examples to illustrate our points…

Thanks. What you say in your comment is quite different to what I took from the post. What you say is certainly much more interesting than what I took from the post.

This is an interesting point. I hadn’t considered this, and I’m not sure I necessarily agree, but I’ll have to give it some thought.

Thanks for the interest in the post; I thought it was going to be ignored! I think Brigitte’s comment is a good precis of our argument, just using different words. I’m glad that’s put it more clearly.

The list of further reading was intended to point to some of the evidence base (e.g. Turner’s article); sorry if that wasn’t clear. Within science and technology studies, the most famous example of non-scientific experts challenging scientific experts was the case of the Cumbrian sheep farmers http://www.dourish.com/classes/readings/Wynne-Misunderstood-PUS.pdf

Finally, to be clear, social scientists should in no way be immune from their own experts/laypeople critique. In the case of transparency in science, I would argue that social scientists who have studied this subject have a claim to being the experts. BUT this does not mean that those scientists who have experience of being at the sharp end have nothing to contribute. Far from it. They are actually akin to the Cumbrian sheep farmers as they are the group(s) with the ‘local knowledge’, in this case of how transparency works (or not) in practice. So, a comprehensive empirical study of the issues involved (which are complex and vary across the different cases) would take into account both the theoretical and empirical evidence base established in the social science literature, AND the experiences and interpretations of the actors involved in the particular cases (e.g. scientists, professional practitioners, non-scientific experts/local publics/patient groups). My quibble with the L&B piece is that it didn’t do the former, and only asked the scientists in the latter.

Thanks for the response.

Didn’t it make it reasonably clear that this was the motivation of their article though? I don’t think it suggested that the former wasn’t an important thing to consider, simply that it was looking at this issue from the perspective of scientists.

The paper you critiqued has the flavor of some arguments against free speech, which can in the short term damage the interests of some. As with free speech, the remedy for troublesome transparency is more of it.

And yet, as far as I can see, it said nothing that could be interpreted as suggesting that anyone should be prevented from speaking freely. Maybe you could point out what it said that could be interpreted as arguing against free speech.

ATTP, I’m not conflating the two. I’m conflating the nature of the arguments supporting it.

You appear to be invoking a “free speech” argument in a situation where there has been no mention of free speech. My view is that this is an attempt to delegitimise something on some kind of fundamental level, rather than actually engaging with what was really said.

No, ATTP, you need to read more carefully.

Some have argued that free speech can be dangerous and should have more limits placed upon it.

The authors of this piece argue that transparency in science can cause problems and should have limits placed upon it.

Different issues, same nature of argument.

The long-standing response to critics of free speech is that the cure is more free speech, not less.

I submit that the correct response to any ‘damage’ caused by transparency in science (waiting for an example) is more transparency.

See ATTP? Different issues. Same style of argumentation on both sides.

Go ahead and struggle to understand.

Hello Thomas. I appreciate your comments on the blog, but I would welcome less snark towards other commenters. Thx, Warren

Hi Warren, okay–sorry if I disrupted the thread.

My point still stands. If the best you can do is suggest that it is comparable to an argument against free speech, then you appear to simply be trying to deligitimise it at some fundamental level without actually engaging with what was actually said.

This isn’t actually what they said. They are not arguing against transparency, they are suggesting that there are various situations in which people might utilise transparency arguments to make cynical attacks on scientists or on scientific results.

As the authors of the study offer no examples of how transparency has boomeranged on scientists, perhaps you can offer one of your own.

And other than calling for data from published studies, are there examples of inappropriate calls for transparency?

In the U.S., politicians from both sides of the aisle have tried to get information about the process of climate science, but you are suggesting something different, it seems.

@ATTP, a personal perspective would be of some interest, but this was extrapolated into a catch-all set of ‘red flags’ of unclear provenance. As we said in the Nature correspondence, this is too important to be left to the research community alone.

The location the piece appeared is also fundamental. A newspaper op-ed is one thing, but a Nature comment piece holds great societal weight (even though it is not subject to the same level of peer review as standard Letters). Right to reply was restricted to below the line, where some good critical points became lost in a maelstrom of points-scoring and opaque moderation practices, ending with a premature closing of the comments.

Warren,

I’m not sure anyone is really suggesting this. I also think there are some subtleties here. There clearly are research best practices and the expectation is that researchers undertake their research in a manner that is consistent with best practice. Policing this, however, is extremely difficult. Employers (universities) can clearly take action when there is evidence of actual fraud/misconduct. Funding bodies can insist on funding being conditional on material being made public. Journals can insist on data been accessible as a condition of publication. However, in my view, any attempt to impose some kind of formal rule would be counter-productive. I don’t know if this is what you’re actually suggesting, but I think it is something to be careful about. I’m also not suggesting that we shouldn’t be encouraging more openness and more transparency, simply arguing against something formal that will probably be too simplistic to be effective and could actually end up being counter-productive.

I must say that I find the rest of your comment a little strange. They published a Nature commentary. It happens. I don’t really see what relevance that has. You could clearly argue that maybe the editors should be more careful in what they publish, but I don’t see why where it was published makes any difference to how one should respond to it. I’d also be interested to know what critical comments you regarded as good. A great deal of the critical comments appeared to be attempts to smear the authors, rather than actually addressing what was being presented. There was the typical whining and claims of censorship when the moderation kicked in. It all appeared rather juvenile to me. If anything, a number of the comments appeared to be illustrating some of the red flags that the authors had highlighted.

You are correct, that no-one was suggesting it explicitly. However, neither did the piece suggest any role for the public. This was the omission we are correcting. I haven’t considered any formal rule. Part of the point is that the cases are very different, as are the social contexts, therefore general rules should be treated with caution. I agree that there are limits on transparency, as Jasanoff argues. Who decides these limits is the question.

The location of the piece doesn’t alter how it should be responded to; it definitely does make a difference to the impact it has on the public debate.

I agree that the behaviour of some, but not all, of the commenters under that post was juvenile. All of us involved in these debates have a duty to reflect on our own behaviour; too many of us have been on a hair trigger in the past on blog comments/social media. This is dangerous because 1) thoughtless comments may have lasting impacts; 2) moderation is expensive for media organisations and is already under intense pressure, shut down in many cases; irresponsible comments will only exacerbate this slide to shuttering BTL. This would be a negative imo, as (transparently!) moderated public comments have a lot to offer.

Which, I agree, seems like a valid extension to the Lewndowsky and Bishop article. This isn’t really what I took from your post, though.

I agree, but there is also a case for making those who aren’t directly involved in fundamental research (who one might call the public) more aware of the complexities of how research is conducted. It’s a two way street. As much as researchers would benefit from a better understanding of the social context in which they conduct their research, others would benefit from a better understanding of the process under which research is conducted. I feel a little as though your argument is placing too much responsibility onto researchers and too little onto others who would like to be involved in some broader way.

Agreed, and it is a pity that people don’t think a bit before responding on blogs (I’m as guilty of this as others).

As far as moderation is concerned, I’ve moderated a blog that, for a while, had a pretty active comment threads. It’s not easy; I probably did it badly; I have a great deal of sympathy for those of who moderate comment threads; I see little evidence that commenters who like to be contentious, show much sympathy towards those who are trying to maintain a comment stream that has some actual value.

Moderation is definitely a skill. I suspect we both had the same amount of training in it before we started (ie zero). The area between being contentious and being ‘over the line’ is tricky. For example, my perception is that the Guardian is getting a lot more ‘contentious’ comments than it used to (across the board, not climate change). This raises an interesting dilemma for moderators; should the emphasis be placed on maintaining a vibrant, often robust, discussion, or is there a point at which positions become so far apart that it damages the overall level of discourse and turns off the Guardian’s core readership/commenters.

Anyway, this is going a bit o/t now, but I think it does have some relevance.

Warren,

In response to AT, you say:

I think the “this” in question is “how the research community should protect its members from harassment, while encouraging the openness that has become essential to science,” as you can lead in bold in the lede.

If I’m correct, then I’m not sure how what you call an “omission” matters exactly. In fact, I think it’s safe to say that the goalposts are shifting a bit. The issue Lew & Dorothy were discussing was the protection from researchers harassment, not how to accomodate the public(s).

Interestingly, the concern similar as yours is raised over and over again in debates regarding women issues: What About The Men? This decoy is so omnipresent there’s an acronym for it: WATM.

While wondering about the public is interesting, I duly submit that What About The Public is not that interesting, Warren.

Thanks for the comment, Willard. To extend your metaphor, if the goalposts are being moved then it is because they were being set too narrowly by L&B.

I’m not following your analogy with “men’s issues”. If you don’t think the role of the public(s) in science is an interesting topic, then of course that is your prerogative. But as I say in reply to Eli Rabett, science must be in the service of society, or else it is nowhere. This does not mean there are not limits to transparency. But neither does it mean that the parameters of the debate should be set in the pages of Nature, based on a very narrow (and sometimes invisble) evidence base.

We are all familiar with controversies within our field. AFAEK and you obviously agree, these can be exceedingly bitter, but they do not include asking for 13 years of their Email as part of your transparency project and Eli suspects Harvey Graff would not consider such attacks as part of a desirable public discourse.

Lewandowsky and Bishop were discussing such attacks, not the broad public discussion and any critique of their piece must start by acknowledging this.

Thanks for the comment. I’m sure we can all agree that asking for 13 years of email is well beyond the pale. However, agreement about one extreme case does not justify the construction of ‘red flags’ that are proposed to be applied across a slew of diverse cases (eg GMOs, climate change, CFS). Any discussion of interactions (positive or negative) between science and society that does not discuss the public interest does a gross disservice to both. If science is not seen to be in the service of society it is nowhere. That does *not* mean submitting to every request ever made; there are limits to transparency, as with everything in life.

I don’t see the problem. They’re simply red flags, not definitive reasons for refusing requests. I was thinking about this a bit more last night. To me there should be a presumption of honesty on both sides. It’s one thing to show some interest in someone’s work and to ask for information and how to go about extending, or understanding what they’ve done. It’s another to suggest that you don’t trust what they’ve done and to request everything so that you can go through it to look for possible errors. The former is standard, the latter is not. Similarly, researchers should assume good faith unless there are reasons to think otherwise; this was largely what the red flags were trying to illustrate.

I would argue that this is simply not true. How science is seen does not change our scientific understanding. Of course, it might change how this understanding influences society, but that’s a slightly different issue. There are very good arguments for why scientists are not expected to be at the beck and call of the public and/or policy makers. They are semi-independent and have academic freedom for a very good reason; it protects them from being pressured into producing results that suite some ideology.

I will add, though, that I’m thinking of what might regarded as normal science; the process by which we gain understanding of some system. Of course, if there is some bit of research that – by itself – will have a huge impact on some decision (policy, or medical) then we may well expect to have to check that far more than we would some piece of work that is simply a smart part of what contributes to our understanding. It seems to me that distinguisghing between these two possibilities would be useful.

“small part” not “smart part”.

At the risk of repeating myself, these ‘red flags’ are not well evidenced, but due to the high-profile nature of the publication they may develop traction (eg cited by COPE, article being referenced in WSJ piece on CFS).

You are alluding to the difference between ‘basic science’ and ‘applied science’. This is a debate I don’t really want to get into here, as there are different perspectives on the extent to which this demarcation is real. However, what I did not mean was that scientists should be at the beck and call of policy makers. *However*, a great deal of funding for science comes from taxpayers. In exchange for the autonomy they are granted, researchers must also be aware of their general responsibilities within society (as all societal actors should be).

In all of the cases cited in the Nature piece, the science clearly does have direct impact on societal actors in some way. Of course, such science should be rigorously checked for robustness. But that is not the only factor. In such cases the science is inherently *politicised*, in that it has the potential for challenging existing practices (defining politics as “a process whereby people persistently and effectively challenge established practices and institutions, thus transforming them into sites or objects of politics” (Brown, 2015)). You can’t get rid of this political dimension, as much as it would be convenient to do so. GMOs are a good example of this; there was no public involvement in the direction of research on the ‘input’ side of research funding policy, therefore all the politics got squeezed to the ‘output’ side (ie challenging a policy presented as a fait accompli). Where protestors saw no alternative to take other part in democracy, they chose a (violent) protest against the science itself. Very disagreeable, but not particularly surprising imo.

Sometimes these effects of the science may be relatively narrow (as with patient groups), or sometimes they might be much broader (e.g. research into geoengineering). But the decisions taken to fund particular areas of research are deeply political, and therefore are likely to attract opposition in some quarters.

Yes, I know, and I’m disagreeing with your apparent requirement that they be well evidenced; I also don’t even know if they aren’t. It was a single comment; it could be a starting point for discussion. Continuing to complain that they’re not well evidence is not – IMO – the way to do so.

On a broader note (and I’ve encountered the same with Dan Kahan). You seem absolutely certain of your position. You’re appealing to evidence that you seem to be suggesting is incontrovertible. This seems somewhat ironic given that you seem to be suggesting that other researchers avoid doing precisely this (i.e., the evidence alone is insufficient to define things; you need to consider the broader context).

Well, I think this is potentially crucial. Plus, it’s not quite the difference between basic and applied science. Even applied science could follow the scientific method, in which no single piece of work dominates a decision. I’m distinguishing between the process of gaining understanding (in which no single piece of work dominates) and the possibility that there are some scenarios (medical research being one possibility) where a single piece of work might dominate.

Yes, but you need to distinguish between “science” that is a collection of work, and “science” that might be a single piece of work. Is there a case in the nature piece in which one piece of work dominates? I’m not suggesting that “science” does not have a direct impact on societal actors, I’m suggesting that there is a difference between a scenario in which our understanding is based on a large collection of work, and one where a single piece of work dominates our understanding.

Not necessarily. If our understanding is based on a collection of work, a single piece of work becomes less relevant. The robustness comes from the continued collection of more information/understanding, not the checking of a single piece of work. This is the scientific method. The rigorous checking comes from other researchers redoing – or extending – what’s already been done; not people wading through the numbers in a single study trying to find errors.

Sure, but this is how it perceived, not necessarily how it is undertaken. That some research may have political influence does not mean that it is inherently politicised.

And you can’t keep imposing it, as much as it would be convenient to do so.

Very unfortunate. And how does this impact our actual scientific understanding of GMOs? Probably little? You appear to be trying to make researchers responsible for the behaviour of people for whom they’re not responsible.

Of course, but funding decisions are not “science”. You seem to be mixing all sorts of things under a single heading

I need to finish the paper I’m writing about this…but to be clear, I am not “entirely certain” about anything, let alone this. (This also seems an unfair characterisation of DK in my experience, although I’m not sure why he has been included in this conversation e.g http://www.culturalcognition.net/blog/2015/7/23/perplexed-once-more-by-emotions-in-criminal-law-part-2-the-e.html)

I think one of the long-lasting problems in discussions on this blog is regarding the entangling of science and politics (and what counts as politics). Different actors certainly have very different perspectives on how these are or are not mixed. Re GMOs, the question that some campaigners ask is not whether individual studies are biased, but why has so much research resources (for which there is an opportunity cost) been expended on, for example, a GM tomato that stays fresh on the shelf for longer. That, in my view, is a political decision about what is or not researched.

My response appears to have ended up in some odd place.

Only because it was another example of an apparent irony I’ve encountered;

Okay, having a bad time here. I wasn’t finished compiling that comment. I might be wrong about the apparent irony, but it’s just an impression I have.

Eli used the example of the demand for 13 years of Email, not only as an extreme, but also as an example of the type of professional (well law is a profession) trolling typical of the GMO, evolution and climate change “controversies”. You appear to be attacking L&B on the grounds that there are no tygers here. There are tygers. How do you propose that scientists and the public cage them?

To quote from a recent piece on dealing with trolling in science communications

http://sciencecommunicationmedia.com/constructively-dealing-with-trolls-in-science-communication/

Okay, but that’s not the impression I’ve had from this post and from this discussion.

Not in mine, but we can agree to disagree. Maybe it’s just with me, but try having a discussion about consensus messaging with DK; either you agree with him, or you just don’t understand it properly (which is a little ironic given that his criticism of consensus messaging appears to be that it’s inherently polarising and explicitly aims to make those who don’t agree seem stupid).

My own view is that people aren’t properly defining what they’re discussing. If you want to define “science” extremely broadly, that’s obviously fine as long as everyone knows what you mean. In a sense, this is a fundamental part of doing research: define your terms.

Agreed, but that – IMO – is not really science (or not what I would mean if I used the term “science”). Science, when I use it at least, is the process of doing research (collect data, run model, analyse data, present results, go to conference,….). The decision as to what to fund is clearly political, however that doesn’t mean that the science is politicised in the sense that the results of the research that is funded

are somehow influenced by this decision (or, at least, I’ve seen no evidence to suggest this). Of course, what we choose to fund will influence our understanding, in that some research will not take place, but that does not necessarily imply that what is done is inherently political.

Okay, to be clear, individuals can be biased and individual studies could have some kind of inherent bias. That’s, however, why we trust the scientific method, rather than individual scientists, or individual studies.

Warren,

You’re most welcome.

You say:

First, it’s not an analogy – asking “What About The Public” is the *very same* rhetorical trick as WATM. It reverses L&B’s question, which is about the researchers’ “rights,” not the public’s.

Second, it is *you* who shifts the topic. Your “but they set it too narrowly!” begs the question at hand – it is not up to you to decide what L&B should talk about.

Third, your counterfactual about my mind states is irrelevant. Asking “What About The Public?” is *independent* from L&B’s question.

Fourth, you’re “this doesn’t mean” is an empty caricature to dismiss L&B’s point, which is, to repeat because you failed to mention it *at least once*, that institutions need to protect researchers who get harassed.

***

Your “but simplistic dichotomy” is a poor excuse to peddle your own pet topic and to handwave to your own field of study. Speaking of which, I think the Harvey Graff’s book costs forty-five US bucks plus shipping :

https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/content/undisciplining-knowledge

This specific “exchange of ideas” around interdisciplinarity does not come cheap. It certainly doesn’t look transparent to me.

Willard, that’s certainly a perspective. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for the post and discussion. I have to admit that I did not read through all of the comments, but I thought that people might be interested in a recently published report that looks at some of the controversies that surround CFS research in the context of their impact upon social and political matters, such as cuts to disability benefits: http://www.centreforwelfarereform.org/library/by-date/in-the-expectation-of-recovery.html

I do think that Lewandowsky and Bishop’s failure to understand the specifics of this particular issue helps to illustrate problems with their strategy. In every case, the specifics matter, and they’re often complicated and uncertain. Those in positions of authority should not be trusted to know what is best, and instead a presumption in favour of openness should be made. Sometimes those classed as vexatious and unreasonable turn out to have been right.

Very interesting comments from David Demeritt. I’ve reading “Universal: A Guide to the Cosmos” by Brian Cox, which is a book the very simply, beautifully and rather poetically takes the reader on a journey showing how, from first principles, one can understand much about the universe.

This is in contrast to, for example, climate change denialists, who delve into tiny corners of contested data to prove, without context, that scientists are liars and the whole climate change thing is fake.

Yes, confusing cherry picking with science is dangerous.

I see that many (if not all) the links provided are accessible to a layperson. That is very helpful to someone like me, who does not work at an academic institution. Thank you.

It’s a pleasure! And thank you for reading! And writing your own lovely blog posts!