May 22, 2013, by Warren Pearce

Bring on the Yawns: Time to Expose Science’s “Dirty Little Secret”

Guest post by visiting fellow, Jeff Tamblyn, film maker and director of Kansas vs. Darwin.

As a visiting fellow in the “Making Science Public” project, I’ve had a great first week at the University of Nottingham, filled by conversations with social science scholars and capped off with the events of May Fest – a day in which the local public received (among other things) a sustained exposure to science. As I elbowed my way through the overstuffed hallways of the Portland building on Saturday morning, the presence of eager crowds playing with exhibits of zoology, microbiology, chemistry and more, strongly suggested that science has many fans. This conclusion, though, reminds me of a question relevant to a study of the relationship between science and the public: Does science need more fans?

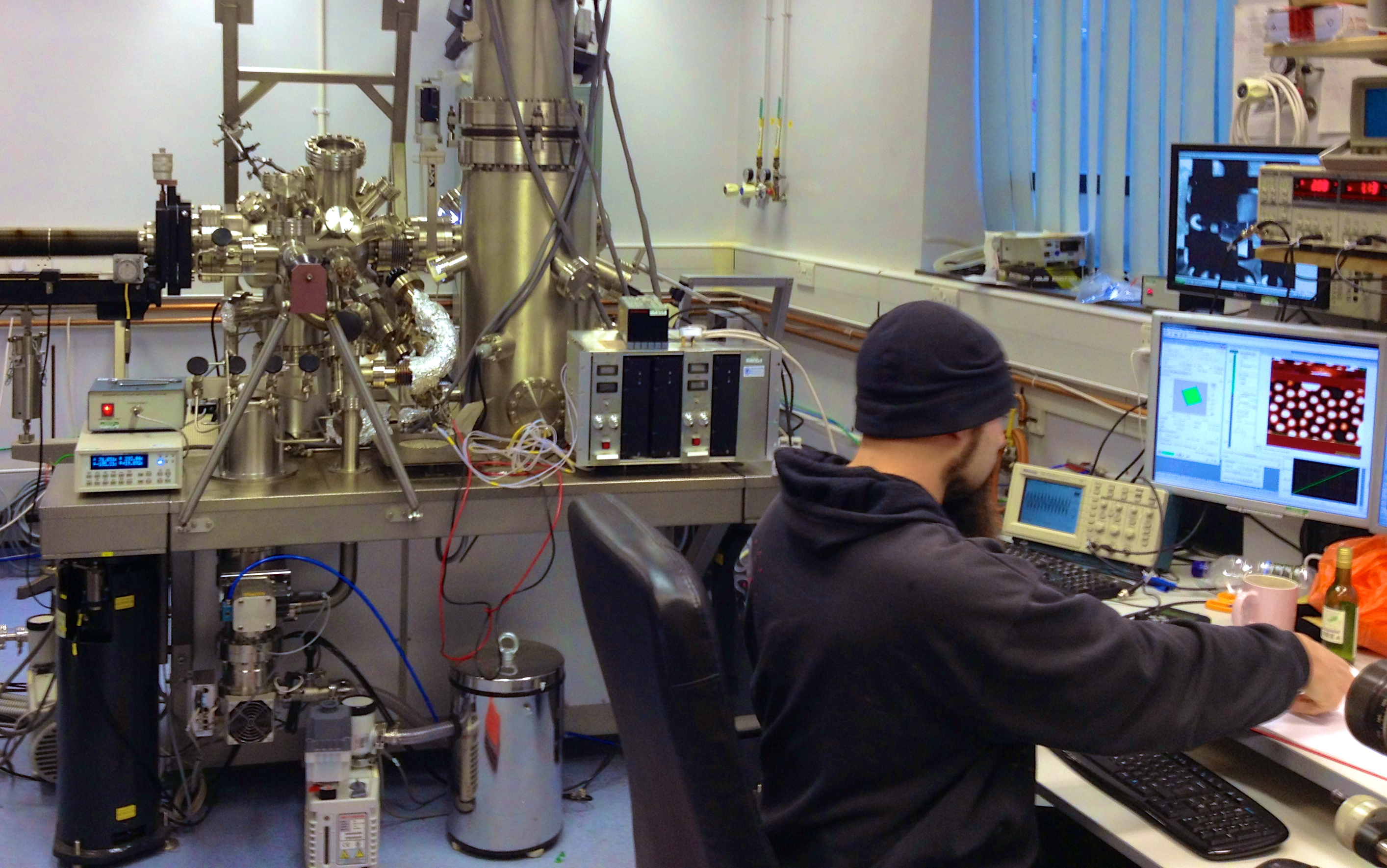

Inside the nano lab

Dr. Philip Moriarty, a professor in the university’s physics department, would likely argue that it does. When I was fortunate enough to visit with Moriarty earlier this week, he proudly gave me a tour of the lab which occupies much of his attention. It’s a room about the size of a one-car garage. In one end hunkers a huge, gleaming metal object comprised of conduits, chambers, wires and instrumentation: an ultrahigh vacuum, low temperature scanning probe microscope.

Moriarty introduces me to his colleague and collaborator, Dr. Adam Sweetman, who’s seated in front of a bank of monitors which bristles with graphics so complex, they make the Big Board in Dr. Strangelove look like an Etch-A-Sketch. Their work involves testing and understanding the bonds between atoms. Moriarty, who’s gifted at explaining science to lay audiences, freely confesses that their work is basic research, the kind with no known practical applications. Not that it will never have any – in a relatively short time, what Moriarty, Sweetman and other nano-researchers discover may help to make machinery such as solar panels even smaller and more efficient. But a relatively short time in science could be years.

Through the microscope

Today, Sweetman’s job is to sit for hours and note tiny fluctuations on the shifting graphs in front of him, indications which will help them figure out whether they’re seeing those atoms they wish to study or merely the tip of the observing instrument itself – a super-tiny filament whose nose is made inevitably of atoms. One of the screens appears to show a collection of ping-pong balls suspended in tomato soup, but the picture seems badly out of focus. “See that?” asks Moriarty. “Those are atoms. You’re looking at atoms on the screen.” This is very cool in itself, but the atoms aren’t moving much. On another screen, the atoms are rendered in black-and-white. It’s a completely different image. As we watch, there’s a slight shift and both Moriarty and Sweetman take note – they’re seeing what they want to see.

As Moriarty explains the workings of the microscope – a half million-dollar instrument which can be purchased ‘off the rack’ these days – I can’t help but notice that parts of it are covered with what looks like aluminum foil, hunks just big enough to wrap a chicken in. Research budgets aren’t close to what they were five years ago when the university bought the microscope, so I can’t help wondering if this is some low-tech ‘patch’ made necessary by lack of funding. (Moriarty tells me later, however, that it’s purely for helping to rid the system of condensed water so the vacuum inside it is unpolluted. Apparently, the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland also uses this technique.) With money being so tight, people like Moriarty and Sweetman are under pressure to produce something usable, something private enterprise can license and manufacture, a piece of knowledge that will create revenue which flows back to the university.

But today, in the lab, there’s no sense of urgency, just a quiet hum of the microscope as Sweetman watches patiently, understanding the screen’s fluctuations because he’s done this for a long time and he knows what he’s doing. In thousands of other labs and field projects across the scientific landscape of the UK and beyond, researchers are performing other monotonous jobs, and this is the reality of science which often escapes the public – unglamorous, long-term investigation.

Science’s dirty secret

Moriarty and I move to a nearby coffee shop on campus and sip Americanos. (Apparently, no one in the UK drinks brewed coffee anymore.) Moriarty reveals a deep concern about a study by another scientist whose conclusions seem unjustified. The quality of the peer review, he feels, is suspect, and the researcher won’t produce all of the original data as Moriarty has requested. Even the journal which printed the researcher’s paper is stonewalling further inquiry. This lack of transparency has plagued science for a long time. The National Academy of Sciences in the US has recently expressed concern about increasing instances of fraudulent research findings. Tight budgets, Moriarty agrees, are forcing many scientists to fudge results in order to get published.

One key to solving these systemic issues might lurk in the hidden truth rather than the visible lies. Despite the science most lay audiences are familiar with – a universe of glossy TV shows, websites, fairs, books and periodicals – science’s ‘dirty little secret’ is that most scientific research produces no breakthroughs or exciting finds. In fact, it isn’t meant to. In order to be verifiable and useful, science is mostly about learning what doesn’t work. It’s about dead ends and back-checking and cross-checking threads of research. It’s about being wrong WAY more than being right. And when money is tight, as it has been increasingly for years, the unglamorous but essential work performed by 95% of scientists is becoming harder to fund.

Process, not products

During our conversation, I suggest to Moriarty that this eventuality is partly the fault of science itself, at the institutional level. The culture of science has for generations programmed the public to expect big breakthroughs and amazing miracles in medicine, physics, exploration, and any brand of science which doesn’t require too much work to understand. It’s worked for decades to keep the public on the hook, while presenting scientists as genius wonder-makers, always on the verge of something game-changing.

The emphasis on the products of science – instead of the process – has denied the modern public a source of knowledge that would help them become more discerning consumers. And today, the public has become more ignorant instead of more sophisticated (if only because science is so much more complex), and therefore easy to misinform about issues such as climate change, early-childhood vaccinations, even evolution, one of the best-understood bodies of knowledge in the world.

Moriarty is dubious at first: “When I talk to schools about science, I don’t want to tell them that it’s boring.” But being a good scientist, he’s willing to consider it. After all, science is about results.

Kansas vs Darwin gets its last screening on Jeff’s UK tour today , May 22, at University of Warwick. Followed by Q&A with Jeff, Steve Fuller and Fern Elsdon-Baker

[…] debate, experiments, problems, and discussion that underpin deep learning. This may well bring on the yawns, but we need to expose students, at whatever level – and, more broadly, any fan of science – […]

[…] film, Kansas vs Darwin, and encouraged him to join our blogging team with two posts on the mundane activities of science and the secret of ‘not doing’. The film made Warren reflect on empty chairs, creationism and […]

[…] debate, experiments, problems, and discussion that underpin deep learning. This may well bring on the yawns, but we need to expose students, at whatever level – and, more broadly, any fan of science […]