January 22, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

Antibiotic resistant infections in the news

In 2015 issues relating to antibiotic resistance and antimicrobial resistance have been widely discussed in the media, by medical experts and policy makers. 2015 ended with reports that antibiotic resistant gonorrhoea is becoming increasingly difficult to treat and that scientists in China discovered a gene in E. coli that makes it resistant to a class of ‘last-resort’ antibiotics and transfers resistance to other epidemic pathogens. Fears about the spread of antibiotic resistant infections are spreading as fast as antibiotic resistance itself.

‘Antibiotic resistance’ is the phrase still most commonly used to describe “the ability of bacteria to resist the effects of an antibiotic. Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria change in some way that reduces or eliminates the effectiveness of drugs designed to cure or prevent infections. The bacteria survive and continue to multiply causing more harm.” Alongside ‘antibiotic resistance’, experts also talk about ‘antimicrobial resistance’ or AMR for short. “Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change in ways that render the medications used to cure the infections they cause ineffective. When the microorganisms become resistant to most antimicrobials they are often referred to as ‘superbugs’.” The term ‘superbug’ normally describes strains of bacteria that are resistant to several types of antibiotics or ‘multidrug-resistant bacteria.’

In June 2015 the Wellcome Trust recommended to replace this type of parlance (antibiotic resistance, AMR, superbugs) by more accurate and more easily understandable terminology, that is, to talk about ‘antibiotic resistant infections’ or ‘drug resistant infections‘. These phrases are spreading very gradually and we will keep an eye on them.

The waning of a wonder drug

Antibiotic resistant infections emerged almost simultaneously with the invention and deployment of antibiotics at the end of the Second World War. The first really significant antibiotic, penicillin, was seen as vital to the allies winning the 2nd World War, as infections that would normally have killed soldiers could now be treated. However, as early as 1945 Alexander Fleming, who won a Nobel Prize that year for his discovery of pencillin, warned in an interview with the New York Times that misuse of the drug could result in selection for resistant bacteria. And: “True to this prediction, resistance began to emerge within 10 years of the widescale introduction of penicillin.” Existing antibiotics, which once were wonder drugs or even ‘magic bullets’, are rapidly losing their power and new antibiotics are not easy to find, develop or bring to market.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) became one of the first widely-known superbugs and is a type of bacterium that can no longer be treated with penicillin. It is one of many hospital acquired infections, which also include Clostridium Difficile or C.diff (studied here at the University of Nottingham within the Clostridia Research Group, now part of the SBRC). Unlike C.diff, MRSA is now moving out of the hospital environment and into the community.

Bacteria, such as MRSA, have gained resistance to antibiotics for a variety of reasons, such as over-prescription, overuse or inappropriate use by humans and overuse in animals that then enter the food chain.

Experts in the UK have been at the forefront of raising the alarm about what some of them, most notably Professor Richard James at the University of Nottingham, called in around 2005 an impending ‘antibiotic apocalypse’, when a “simple cut to your finger could leave you fighting for your life” (BBC 19 November 2015, Analysis: Antibiotic Apocalypse http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-21702647). His and many others’ calls for action now seem to be heard by politicians, such as Prime Minister David Cameron, and policy advisors, such as Dame Sally Davies, the UK’s Chief Medical Officer. See also her 2013 Penguin book entitled: The Drugs Don’t Work: A Global Threat.

The role of the social sciences

Beyond medical and natural science experts, social science experts are increasingly being called upon to find solutions to the problem of drug resistant infections. In 2015 the ESRC has appointed an AMR Research Champion, Dr Helen Lambert, who has pointed out that the “rise of resistance to antibiotics (Anti-Microbial Resistance, AMR) is largely a consequence of human action, and is as much a societal problem as a technological one.” Thus, it appears necessary to promote behaviour change in order to redress the emerging threat of antibiotic resistance.

Many of these global and national activities are intended, implicitly or explicitly, to start a societal conversation about AMR, that is, to get people, users, producers, scientists, farmers, talking about AMR, to make AMR ‘public’, as my colleague Sujatha Raman points out.

So it is a surprise to see that one can find only relatively few instances of communication or media researchers getting involved in the social science study of AMR (see references at the end of the blog post). In previous work on public understanding of climate change, we have argued that people need to be given the ‘resources’ (such as metaphors, images and anchors) to think and talk about complex and esoteric scientific phenomena. This is also relevant to the debate on antibiotic resistance.

In order to determine the state of public conversations and public communications, to assess where the talking points are, what the silences are, what is foregrounded or backgrounded, who or what is blamed, what solutions are being discussed etc., it is necessary to examine how AMR is talked about in the public media, in traditional as well as online media, as these are the main fora for public discussion on a national and global level. Moreover, the type of language used will at least contribute to the perceptions that people develop about antibiotic resistance.

In this blog post we want to dip our toe in a torrent of potential data by focusing on traditional media coverage, in particular English speaking press coverage, and more particularly still press coverage in the UK. We want to first trace the contours of that coverage before homing in on its beginnings. We will conclude with an outlook on research still to come.

Contours of the debate as seen through the eyes of UK press coverage

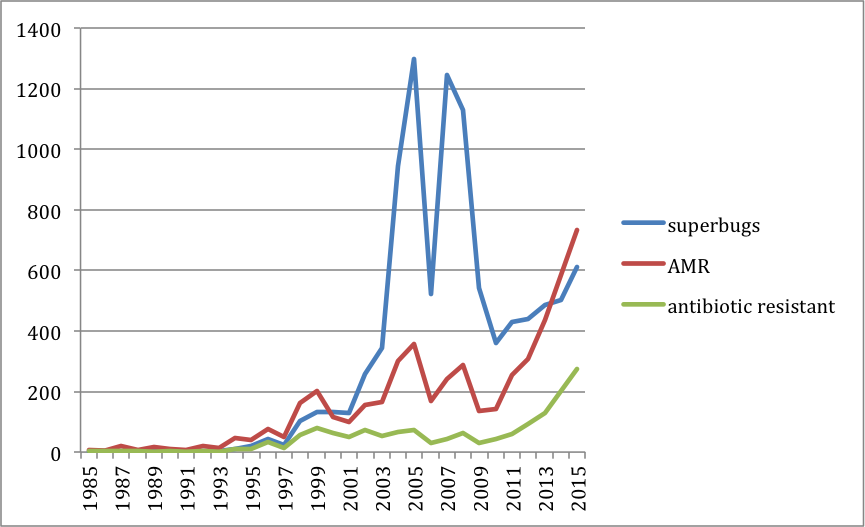

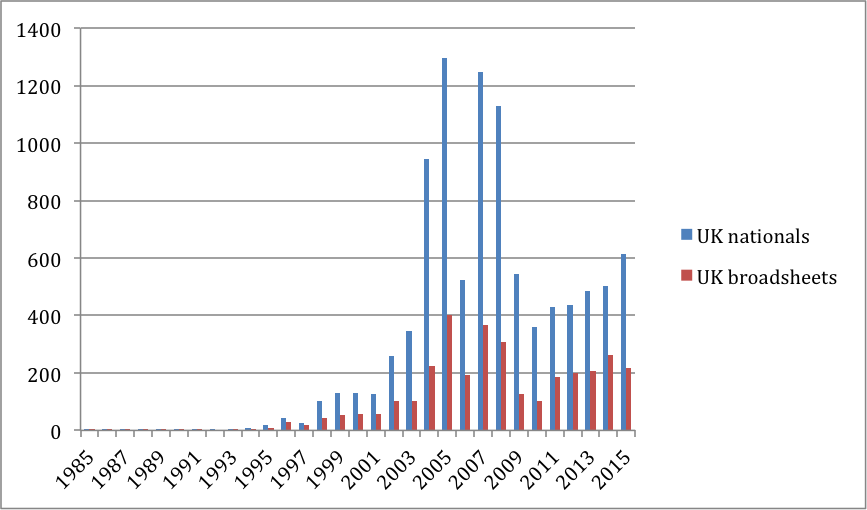

In a first step we searched the news database Lexis Nexis using a selection of keywords. We focused on UK National Newspapers (which comprise both tabloids and broadsheets) and looked for news items using the search terms ‘antibiotic resistance’ OR ‘antimicrobial resistance’ (called AMR on the graph), as well as ‘superbug’. As we’ll detail in the next section, the adjective ‘antibiotic resistant’ was first used in The Times in 1961 and is the first attestation and the only one for ‘antibiotic resistance’ in the Oxford English Dictionary. So we added this to our search too.

The resulting graph shows that the contour of the ‘superbug’ coverage is quite different to that the ‘AMR’ coverage. Both types of coverage began in the 1980s, took off in the 1990s, but peaked differently, with ‘superbugs’ making the news between 2004 and 2008, while AMR had a slight peak at the same time but has been garnering more and more coverage over the last few years, indicating a shift from ‘scare stories’ (about killer bugs etc.) to a more science-based approach to alerting people to the dangers of AMR.

When looking more closely at the reason for the superbug peaks, we found that tabloid coverage drove the debate about superbugs, in particular MRSA in the early 2000s, while broadsheet coverage is now driving talk about AMR.

The beginnings of the debate in the English public press

AMR

In order ascertain when the words and phrases ‘superbug’ and ‘antimicrobial/antibiotic resistance’ were first used, we turned to the Oxford English Dictionary. We found that there is an entry for ‘superbug’ but none for ‘antibiotic resistance’ or ‘antimicrobial resistance’. However, the phrasal adjective ‘antibiotic-resistant’ is attested: “1961 Times 17 Mar. 5/4 Of the antibiotic-resistant staphylococci..90 per cent were isolated from infants born in the hospital.” We could not find this article in the Nexis database, however. The database is known to have some gaps.

To find out when our search terms were first used in English news, we then searched ‘All English Language News’ on Lexis Nexis from 1950 to 1990 and found two quite interesting start dates for these two overlapping types of coverage. Let’s look at AMR first, as ‘superbugs’ have quite a different origin story.

The topic of ‘antibiotic resistance’ was first covered in the New York Times in the context of UK farming in the year 1969, when The Swann report on the use of Antibiotics in Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine was issued. The article, published on 21 November 1969, says: “Brit Govt to restrict use of antibiotics for farm livestock after study reveals possible health hazards to humans; study, conducted by Prof Michael M Swann, urges that only antibiotics with little or no med value for animals or humans should be used in feeds; curb linked to findings that certain antibiotics can lead to emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains in humans; Brit Med Assn lauds action; Natl Farmers Union scores [sic] it; Agr Min Hughes comments; FDA says US has not banned antibiotics from feed”. This is the beginning of a long story that is still not quite over. While the EU has banned antibiotics in animal feed, the US is still wavering from a complete ban.

Antimicrobial resistance by contrast makes its first news appearance in 1984 in the journal Chemical Week (10 October, 1984). 1984 is also the beginning of our story when we get to the UK press coverage in particular. The article in Chemical Week is entitled “Antibiotics in animal feed” tells a now all too familiar story beginning in 1949, just after antibiotics had proven so useful during the Second World War: “In 1949, when antibiotic use was still in its infancy, Dr. Thomas Jukes stumbled on the curious fact that baby chicks fed chlortetracycline gained 10-20% more weight than other chicks. Jukes, then a research director at American Cyanamid’s Lederle Laboratories, found that piglets that were fed the antibiotic did even better. Jukes’s discovery led to an antibiotics market now worth $250 million each year to U.S. drug makers. This year, more than 9 million lb of antibiotics — about 40% of all antibiotics made in the U.S. — will be sold as feed additives for livestock by a number of drug companies, including American Cyanamid, American Hoechst, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and SmithKline Beckman. In promoting growth, antibiotic additives also enable farmers to use less feed to produce more meat. The economics of antibiotic use have proved irresistible”. And they still do; the story continues to this day!

The article then goes on to examine the problem and reports on a study carried out by the US Centres for Disease Control, which “concluded that antimicrobial-resistant bacteria can be transmitted from animals to humans, causing serious disease, particularly in people already taking antibiotics. Levy, a long-time advocate of restricting antibiotics use in feed and president of the Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics (Boston), hailed this conclusion in his New England journal editorial. ‘Surely, the time has come to stop gambling with antibiotics,’ Levy wrote in a plea to ‘reserve these valuable resources for fighting microbial disease.’” Yet again, this sounds extremely familiar to modern ears.

Superbugs

What about ‘superbugs’? When did they begin to be discussed in ‘All English Language News’? Here the story is more complicated. The word ‘superbugs’ was first used in the context of biotechnology to refer to genetically engineered bacteria, enhanced, initially through recombinant DNA, to make them useful for specific purposes. Such bacteria are much in the news again, although without the label ‘superbugs’ being used, as synthetic biologists (here at the University of Nottingham for example) are trying to develop strains of bacteria that can be used to produce biofuels or plastics for example. This first meaning of ‘superbugs’ can be found in a Newsweek article of 21 March, 1977, which reported on “’superbugs’ for cleaning up oil spills”. This use of the word continued until about 1985. Then things changed and the word began to take on its modern meaning of ‘strain of bacteria that has become resistant to antibiotic drugs’. An article published in the New York Times in April 1985 said for example: “Antibiotics routinely placed in cattle feed lead to ‘superbugs’, which once inside a human host are untreatable with the drugs to which they have become resistant”.

Our project

In UK national newspapers too the first use of the new meaning of ‘superbugs’ can be found in 1985, when The Guardian reported on “‘superbugs’ resistant to antibiotics” on 21 December, again in the context of ‘livestock’. In a forthcoming article we’ll home in on the way that AMR has been reported in UK national newspapers by focusing in particular on the use of the phrase ‘antibiotic resistant’, its ‘collocates’, i.e. words surrounding this phrase and the political contexts, implications etc. of the use of such words and phrases. Consistent with our other research into science and society, we will draw upon metaphor theory and social representations theory and will use a mixture of quantitative corpus linguistics and qualitative text analysis. We will see how agriculture as general background topic fades out over time, to be replaced by discussions about the dangers of MRSA, TB, hospital acquired infections more generally, killer bugs, discussions of solutions, such as hand hygiene, ancientbiotics (discovered here at the University of Nottingham) etc., before coming back up on the horizon more recently. Our project team consists of myself, Brigitte Nerlich, Rusi Jaspal (De Montfort University, School of Applied Social Sciences) and Luke Collins (University of Nottingham, School of English).

A selection of articles on AMR in the press – and related issues

Burnett E., Johnston B., Corlett J. & Kearney N. (2014) Constructing identities in the media: newspaper coverage analysis of a major UK Clostridium difficile outbreak. Journal of Advanced Nursing 70(7), 1542–1552.

Nerlich, B. (2013). When the mundane becomes threating: Raising the alarm about antibiotic resistance. Making Science Public Blog: https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/makingsciencepublic/2013/03/24/antibiotic-apocalypse/

Nerlich, B. and Koteyko, N. (2009). MRSA – Portrait of a Superbug: A media drama in three acts. In: A. Musolff and J. Zinken, eds. Metaphor and Discourse. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 153-172.

Nerlich, B. (2009). “The Post-Antibiotic Apocalypse” and the “War on Superbugs”: Catastrophe Discourse in Microbiology, its Rhetorical Form and Political Function.Public Understanding of Science, 18(5), 574-588; discussion by Richard James: 588-590.

Brown, B. Nerlich, B, Crawford, P., Koteyko, N, and R. Carter. (2009). Hygiene and biosecurity: The language and politics of risk in an era of emerging infectious diseases. Sociology Compass, 2, (6): 1–13.

Koteyko, N., Nerlich, B., Crawford, P. and N. Wright (2008) “’Not rocket science’ or ‘no silver bullet’? Media and government discourses about MRSA and cleanliness”. Applied Linguistics, 29, 223-243.

Crawford, P., Brown, B. Nerlich, B. and Koteyko, N. (2008). The ‘moral careers’ of microbes and the rise of the matrons: An analysis of UK national press coverage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Health, Risk and Society, (17): 331-347.

Saliba, V. et al. (2016). A comparative analysis of how the media in the United Kingdom and India represented the emergence of NDM-1. Journal of Public Health Policy, 37, 1–19

Washer, P. and Joffe, H. (2006). The “hospital superbug”: Social representations of MRSA. Social Science and Medicine, 63(8), 2141–2152.

Image: Dr Graham Beards at en.wikipedia: Antibiotic resistance tests; the bacteria in the culture on the left are sensitive to the antibiotics contained in the white paper discs. The bacteria on the right are resistant to most of the antibiotics.

Very interesting post. Bit disturbing how many decades have passed since the first warnings.

I have the impression this ‘new wave’ of warnings about AMR is stronger, longer lasting and more persistent than the last. It also seems to be more global…. Let’s hope it works!

A very interesting research post. I’m writting a short essay on superbugs, and I was wondering if it would be possible to include the first graph (citing the authors and procedence, of course), or if this graph has some copyright.

Thanks in advance and kind regards,

Albert Figueras

Professor

Dept. Pharmacology and Therapeutics

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

(Spain)

Yes, of course, you can use it with attribution. You might be interested in this article too http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1363459317715777