July 30, 2015, by Brigitte Nerlich

Ants and the art of science communication

Ants have been in the news this week. First there was Jim Al-Khalili’s interview with E. O. Wilson, a world authority on ants, for The Life Scientific. Then there was the announcement that scientists at the University of Cambridge (funded by the BBSRC) have discovered that ants use three types of hair to meticulously clean their antennae. This came to my attention through a research note in Nautilus Magazine but was also reported more widely in a Daily Mail article which contains a series of really intriguing images and a video. All this sent me back down memory lane to my childhood, my fascination with bugs and worms and my interest in (science) illustrations.

Ciondolino

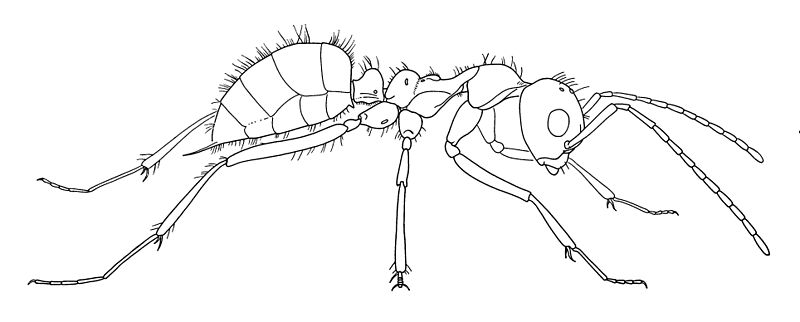

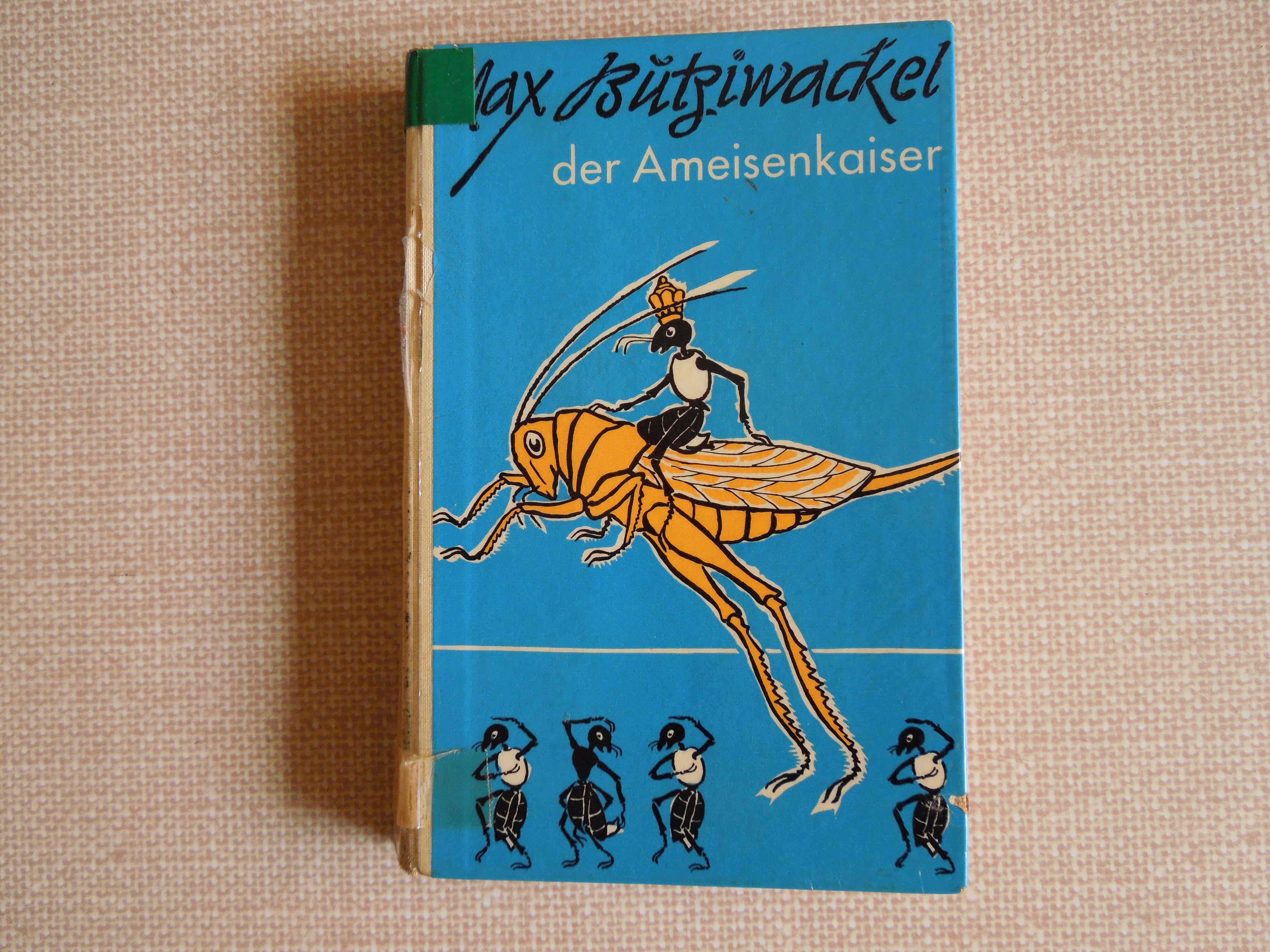

At the age of about nine (the same age that Wilson started to be intrigued by ants a few decades before me ;)), I came across a book that I loved to read. It is called Max Butziwackel der Ameisenkaiser [Max Butziwackel, the Emperor of the Ants] by Luigi Bertelli – don’t laugh, or rather do laugh, it is a rather comical title (but actually a relatively good translation of the original Italian title Ciondolino – referring to a little piece of cloth that was always hanging out of Max’s trousers and survived his transformation into an ant). The book first appeared in Italian in 1895 and was translated into German in 1920. The title of the English translations are more sober: The Prince and His Ants (1910 edition) and The Emperor of the Ants (1935/37 edition) illustrated by Attilio Mussino. I myself read the 1962 German edition which one can still buy. This means, I read it at a time, but, of course, totally unaware of, when Wilson, Carpenter and Brown’s published their seminal 1967 article on Mesozoic ants which contained some nice illustrations – and I have used their ‘figure 1’ as the featured image for this post.

Max Butziwackel tells the story of three young children who are turned into a grasshopper, a butterfly and an ant egg with the focus on the ant. Max grows from an ant egg to a full ant and then becomes the emperor of the ants. The book appealed to me because Max, whom this happens to, was idly watching an ants trail while he should have been studying his Latin Grammar. Once an ant, Max makes friends with Fuska, a worker ant, who teaches him, and of course this reader who read about Max’s adventures instead of learning her Latin grammar, all about ants.

Max Butziwackel tells the story of three young children who are turned into a grasshopper, a butterfly and an ant egg with the focus on the ant. Max grows from an ant egg to a full ant and then becomes the emperor of the ants. The book appealed to me because Max, whom this happens to, was idly watching an ants trail while he should have been studying his Latin Grammar. Once an ant, Max makes friends with Fuska, a worker ant, who teaches him, and of course this reader who read about Max’s adventures instead of learning her Latin grammar, all about ants.

I had seen ants often enough when playing in the woods, but now I came to see them in a new light. This ant hill in particular always fascinated me and my friends. It can be found when walking along a ‘Waldlehrpfad’ or forest learning path near the village we lived in. When studying the ant hill (and sometimes prodding it a bit), we were particularly interested in the ants’ ‘washing behaviour’ which was also a big topic in the book I read at the same time. While being an ant, Max learns quite a lot about cleanliness, something that, like Latin grammar, he hadn’t been so keen on as a human boy!

I had seen ants often enough when playing in the woods, but now I came to see them in a new light. This ant hill in particular always fascinated me and my friends. It can be found when walking along a ‘Waldlehrpfad’ or forest learning path near the village we lived in. When studying the ant hill (and sometimes prodding it a bit), we were particularly interested in the ants’ ‘washing behaviour’ which was also a big topic in the book I read at the same time. While being an ant, Max learns quite a lot about cleanliness, something that, like Latin grammar, he hadn’t been so keen on as a human boy!

Ants and science

Now, about half a century later, scientists have not only discovered the most amazing facts about ants (thanks largely to E. O. Wilson’s work), they have also discovered how this washing and cleaning happens! Research into ants’ complex cleaning tools was published in a paper by Alexander Hackmann, Henry Delacave, Adam Robinson, David Labonte and Walter Federle, entitled Functional morphology and efficiency of the antenna cleaner in Camponotus rufifemur ants

As the press release says, “Camponotus rufifemur ants possess a specialised cleaning structure on their front legs that is actively used to groom their antennae. A notch and spur covered in different types of hairs form a cleaning device similar in shape to a tiny lobster claw. During a cleaning movement, the antenna is pulled through the device which clears away dirt particles using ‘bristles’, a ‘comb’ and a ‘brush’.”

Understanding how ants clean themselves is great. But there is more: this understanding might enable researchers to build “bioinspired devices for cleaning on micro and nano scales”. This is extremely important when imaging the nanoscale and when ‘building’ at the nanoscale, as any nanoscientist can tell you! As the full paper points out: “Analysing the detailed biomechanics of cleaning mechanisms in insects may also help to uncover principles relevant for synthetic cleaning of surfaces at the micro- and nanoscales, such as in the fabrication of delicate semiconductor and microelectronic devices, where contamination can lead to a substantial number of defects and reduction of the manufacturing yield.”

Ants and art

My edition of Max Butziwackel has a few illustrations (see above). These remind me, now that I have delved back into ants after about 50 years, of the illustrations in E. O. Wilson and Bert Hölldobler’s book of 1990 The Ants (a popular version entitled Journey to the Ants was published in 1994). The original Italian version of the ant book I so loved as a child, published a century before Wilson’s book, contained 120 black and white illustrations und 8 colour plates by Carlo Chiostri who also illustrated the first edition of Pinocchio in 1901. I tried to find this edition and the illustrations on the internet, but to no avail. I only found a single example of an illustration, in this case a moth, for the original Italian version of the book. I’d really love to see more of these – so if anybody knows where to find them….

In 2010 Wilson wrote a novel entitled Anthill. One part of this novel has been published in The New Yorker under the title Trailhead. Max who, in my childhood book, advances from foot soldier to general to Emperor of the ants would have felt right at home in this story about the Trailhead Queen. Here is a taster: “The signals now proclaimed, Food. I have found food. Follow my trail! Soon a mob of ants ran out, followed the trail, and gathered around the delicious grasshopper haunch. Some of the first to arrive ran back to the nest, laying trails of their own, reinforcing the message, saying, Come on, come on, we need help. The ants still by the grasshopper piece began to drag it toward the nest entrance. A catbird perched on the branch of a nearby tree saw the activity and swept down to investigate. She pecked at the grasshopper, scattering the ants and injuring several. The ants expelled a pheromone from a gland that opened at the base of their jaws. A chemical vapor spread fast. It shouted, Danger! Emergency! Run!”

As one reviewer of the story said: “This is not science. This is experience — the stuff of all fiction.” This was exactly how it felt for me when I was reading one of my favourite childhood books. We learn, but we are not being taught. This is the art of science communication.

Image: An ant drawing by Wilson, Brown and Carpenter (Wikimedia Commons)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply