May 25, 2014, by Brigitte Nerlich

Going round in circles?

As some readers of this blog will know, there has been a conference last week here at the University of Nottingham, which brought together social scientists and natural scientists to discuss issues related to science, politics and the media. The conference was entitled: ‘Circling the square: Research, politics, media and impact’. [Just after I posted this post, Philip Moriarty sent me his take on the science politics issue, which you can read here – there are certainly some overlaps between what say below and what he says in his post]

As some readers of this blog will know, there has been a conference last week here at the University of Nottingham, which brought together social scientists and natural scientists to discuss issues related to science, politics and the media. The conference was entitled: ‘Circling the square: Research, politics, media and impact’. [Just after I posted this post, Philip Moriarty sent me his take on the science politics issue, which you can read here – there are certainly some overlaps between what say below and what he says in his post]

Science and communication

In blog posts written after the conference, some natural scientists expressed genuine consternation about the ways in which they thought social scientists had portrayed natural scientists, for example as bad, naïve, or ill-advised communicators. I remember chatting to a group of people after one of the panels and trying to stress that this stereotype was just not true. So, for all those who are still reflecting on this issue, please read Tim Radford’s refutation of this myth (which is, it should be stressed, not only perpetuated by social scientists) and look at the blog posts these poor communicators have written after the conference!

Science and politics

Many natural scientists I spoke to were also puzzled by claims about the inextricably political nature of science. This issue perplexed me too and has bewildered me for a long time. I think the crux of the problem lies in conflating science as ‘the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behaviour of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment’ (Google definition) with using science for policy making or engaging in science advice.

After one of the panellists, Beth Taylor (until recently Director of Communications and International Relations at the Institute of Physics), told us about her experiences when dealing with communication issues around nuclear waste, I was tempted to ask the audience to carry out the following Gedankenexperiment or thought experiment. I did not do this at the conference, but I want to do this now in this blog post:

Imagine you are a policy maker who has to decide where to relocate a nuclear waste dump threatened by coastal erosion. You want to get things right, so that you don’t get into that situation again and you don’t want to lose the trust and support of the communities affected. So you go to ‘the scientists’ and ask them to supply you with as much information as possible about tidal patterns, coastal erosion, geology, seismology, geography, patterns of road use, etc. etc. You then go to your communities and say: ‘OK, we have to make a decision about how to relocate this nuclear waste. Here is the information supplied by the scientists. Of course, you will also have to take into account your own wishes, worries and values. Now tell me what you think and help me to make my final decision as a policy maker’.

However, if the claim about the inextricably political nature of science is true, then the policy maker would have to go to the community and say exactly what he or she said before, but then add a caveat: ‘but of course, you have to keep in mind that all the scientific information which the scientists have supplied is political (biased, value-laden) in nature. Now make up your minds!’

I believe that this just would not work. Or am I completely misunderstanding something here? I am still trying to learn about science and politics.

Of course I don’t deny that there are political issues which impinge on science (funding and the impact agenda come to mind, as well as the corporatisation and marketisation of universities) and, even more so, on the use of science in political decision making. I also don’t dispute that scientists have to be extremely careful and totally honest about the limits of what they do and say when stepping into the political sphere or mingling with politicians. This does not mean, however, from my still rather naïve perspective, that basic science itself, the process of gathering robust and reliable information about an issue, is an essentially political pursuit. If that was the case, how would we ever make political decisions about anything where we need scientific information? Would we just toss a coin in the end?

And what would happen if we also applied this principle of the inextricably political nature of science to the social sciences (see the comment by Victor Venema here)? Could we still trust what social scientists say about the nature of science, about science and politics, about scientists and so on? Wouldn’t this lead to a rather vicious circle?

Breaking the circle?

So, what I would like to see is a blog post by a core social scientist, with much more knowledge about these issues than me, who can explain to me and probably many others what the inextricably political nature of science means and what it entails for the natural as well as the social sciences and the status of knowledge and expertise in our society.

A good start may be for us all to read and discuss this 2013 Guardian science blog by Sheila Jasanoff who contributed strongly to the conference and has a wealth of knowledge and experience on such matters.

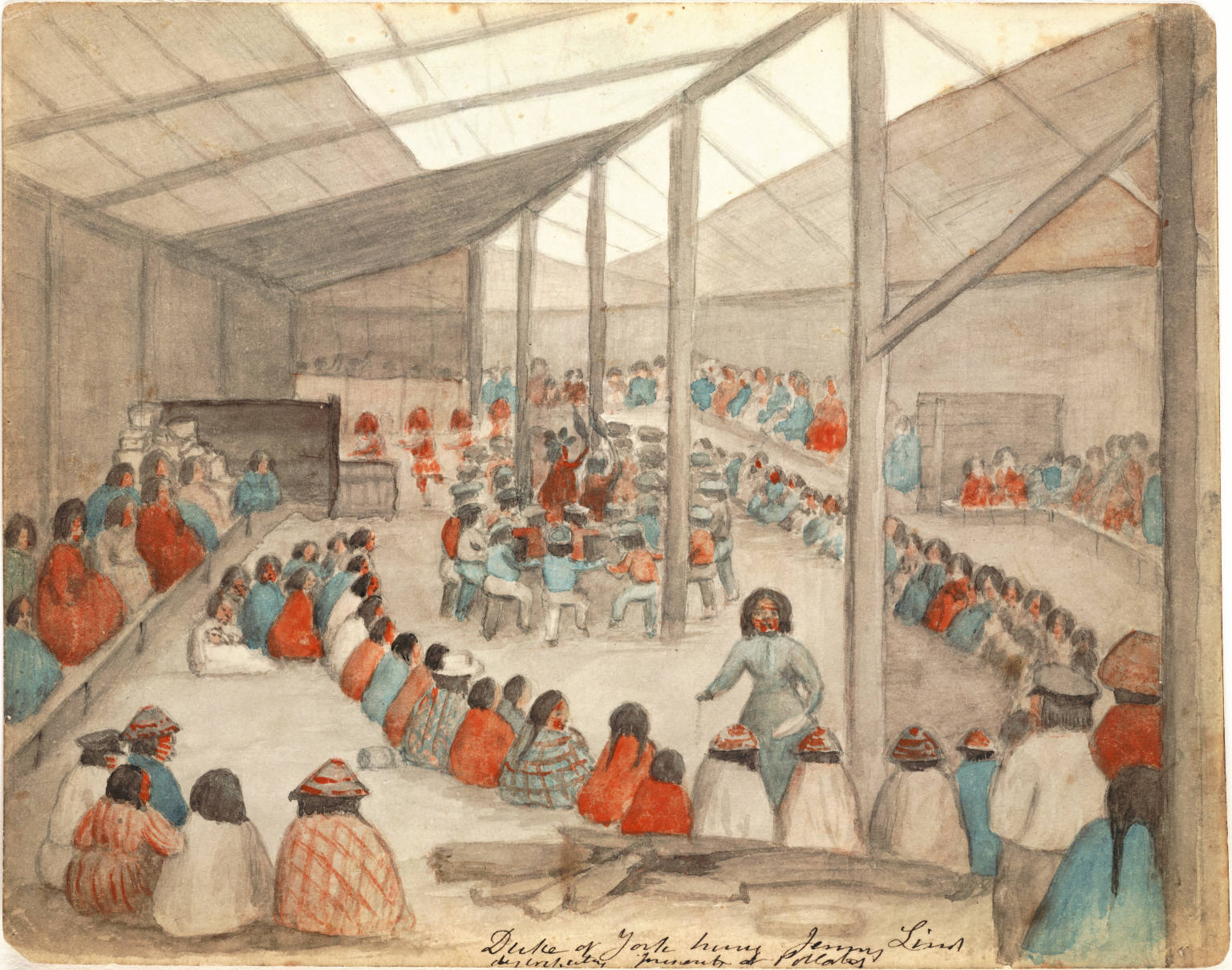

Image: Klallam people at Port Townsend (Wikimedia Commons)

Brigitte,

Interesting post. I was following the comments on Athene Donald’s post. Some very interesting comments, but there was a suggestion that one issue is that STS research involves studying scientists and hence – if scientists don’t like the results – they may suggest that the research is flawed. Firstly, I can see how this could be part of STS research, but I had thought STS was much broader and more about the societal influences of science/technology, than about studying scientists specifically. The other thing that struck me is that all the biases that could exist in scientific research, presumably also exist in STS research. So, if STS researchers are studying scientists, who studies the STS researchers? Personally, it would concern me is there are STS researchers who really think that somehow they are the checkers of scientific practice.

Yes, that what I was wondering about myself. I bet there are pieces of research or blogs or whatever where STSers reflect on their own potential biases, the political influence on their research practices and so on. I hope some STS experts will supply them in the comments! It would certainly be strange if they didn’t exist. I would also say that as far as I understand STS it IS much broader than putting scientists under the microscope (and I bet Reiner didn’t want to imply that STS can be reduced to this activity) – and again I would hope that ‘scientists’ in this context also means social scientists. Reflexivity is after all a key word in the social sciences!

Something else that struck – from reading some of the posts about the meeting – was that there was a general agreement that things like the impact agenda, commercialisation of universities and REF are have an impact on the behaviour of academics. This seems to be something that STS researchers might be looking at. Is much of this happening? (I guess that since this is something that academics already regard as having some impact, it would still be research that wouldn’t be free of some sort of bias)

Good point. One of my former colleagues, Robert Dingwall, was interested in the impact of measurement on academia but I can’t find any output by him on the topic… At the moment one of my colleagues at the School of Sociology and Social Policy, John Holmwood, is certainly interested in the impact of the impact agenda on academic life and in particular on sociology. However, off the top of my head I can’t think of any empirical research into this matter…. This might be of interest though, by John: http://www.methodologicalinnovations.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/5.-Viewpoint-Holmwood-13-17-proofed.pdf

A very interesting post, Brigitte.

Thinking about your question as to whether “the process of gathering robust and reliable information about an issue” is inherently political – I’d return to David Nutt’s comparison of the dangers of horse-riding and ecstasy. The process of collecting cause-of-death statistics is very likely apolitical (although there are interesting country differences regarding causes such as heart disease that may reflect reporting biases). So on one level Nutt was just making a factual statement in saying horse-riding is more harmful than ecstasy.

But why choose horse-riding as a comparison (rather than boxing or rugby for instance) – was it because it is a sport that middle-class parents are happy to see their daughters take up? Was it a response to what Nutt saw was a highly politicised use of evidence on the other side? For instance in his essay linked below, Nutt noted that one study found that only 1 in 250 deaths due to paracetamol was mentioned by the press, while every ecstasy death was reported.

Or was it just that the pun ‘Equasy’ was too good to miss?

Equasy – A Harmful Addiction

Good point, but that’s why I said that scientists have to be brutally honest with themselves and with their audiences, be they politicians or the general public, once they start interacting with them and why a good interviewer might have asked David Nutt, why did you choose this comparison rather than another? However, choosing this comparison is a political act, not a scientific one, in my view at least.

Ruth, since you’ve mentioned David Nutt, wasn’t that a classic case of a scientist blurring the advice/advocacy boundary? From memory – and I may have some of this wrong – his conflict with the government seemed to revolve around the government not doing what the evidence suggested. I found that whole situation rather unfortunate. As an adviser, it seemed that he was pushing very hard for specific policy changes, rather than simply giving the best possible advice. I have no issue with scientists advocating when acting in their personal capacity, but doing so when formally an adviser did seem to be questionable. Again, I may be mis-remembering this somewhat.

Perhaps if you could give a specific example of what Nutt said, it would be possible to discuss at what point ‘giving the best possible advice’ differs from pushing for policy changes, if the adviser sees that as the ‘best advice’ that he can give. Tamsin Edwards received considerable criticism for saying that in her view scientists should refrain from advocating particular policies. But discussing what you vaguely remember does not seem very productive.

David Nutt’s comparison of horse-riding and ecstasy was mentioned in Steve Rayner’s talk – hence my link to what Nutt wrote on the topic.

Well, I had assumed that this was sufficiently big issue at the time, that others might have some memory of it too. It just seemed to be an example of someone who went slightly further than simply giving objective advice and then leaving the policy makers to use that advice as they saw fit. There were plenty of articles about this, which you could find easily if you were interested in doing so. I do realise, however, that this is somewhat off topic.

It was partly because of Tamsin’s article that I had thought of this. I realise that Tamsin received considerable criticism because of her article. Her argument – if I remember correctly – was that scientists should not advocate as that would appear to damage their objectivity/credibility. It seemed, to me at least, that David Nutt came pretty close to doing exactly that (and was – I believe – asked to step down from his position as Chair of the advisory panel) and yet I don’t think that anyone suggested that this damaged his standing as a scientist. My own personal views is that it shouldn’t and didn’t, and I would argue that the same applies in most other similar circumstances too. It seems much more likely that a scientist might cross the advice/advocacy boundary because of their understanding of the evidence, than – as I think some have argued – that advocacy implies that a scientist’s policy preferences are influencing their research. This is, however, getting rather off topic, so apologies for bringing it up.

This might help http://medicnews.wordpress.com/2009/11/01/the-ecstasy-and-horse-riding-debate-the-story-behing-professor-nutts-sacking/

It seems to illustrate my point that the choice of horse riding as a comparator was a political/strategic/rhetorical one and it worked, it was very effective. It’s now engraved in collective memory. I still remember the morning I heard him use that analogy on radio 4! But of course you would have to ask Professor Nutt why exactly he chose this analogy in the first place rather than another.

[…] the Square continue “below the line” of a number of insightful blog posts. (And mine). [And mine, […]

[…] on Sunday morning (25 May) both Brigitte and Phil mused again about the issue of science and politics and, hold the headlines, largely […]

The comment from Reiner Grundmann on my blog http://occamstypewriter.org/athenedonald/2014/05/21/social-scientist-for-the-day/ suggested I might feel uncomfortable with STS researchers because they look at scientists. I think that is completely missing the point. One of the things that worries me is that there is the danger in these studies of treating scientists as a homogeneous whole. To take a slightly high temperature example some, like Philip Moriarty, wouldn’t touch impact with a barge-pole and others have no trouble doing science that they can easily describe within an impact envelope. This means both that there is a political element to the science (not in how it’s done but what is done) and that scientists come in many complexions. Yet, too facilely, we are treated somewhat homogeneously. In my review of Harry Collins’ book Are we all scientific experts now http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/books/are-we-all-scientific-experts-now-by-harry-collins/2011520.article that is one of my key concerns with how he tackles his subject.

I am sorry I missed Pielke’s talk, although I have read his book, and I find it hard to know what he means the honest broker actually is. A scientist who never expresses an opinion, I think, someone who merely states the facts and leaves it to others to put an interpretation on it. I am not sure I don’t think that is abrogating some of our responsibilities. That is where I think the real debate needs to be, at the interface between policy and science, not scrutinising how scientists go about their work. Flawed work will out. Scientists who back flawed work will in general suffer. To give an historical example, think of Lysenko in Stalinist Russia and the loss of credibility Bernal (who was absolutely not a geneticist and allowed his Marxist leanings to get in the way of the science) suffered by backing him.

I agree with you that we have to get away from talking about ‘science’ and ‘scientists’ as homogeneous entities. In fact STS is very keen on pluralising knowledge and public, so the same should happen for science. I once quipped that science did not exist; it happens, to drive home that point. I also think that if scientists discover certain things (make certain findings) that are indicative of certain courses of action, then they have a right, indeed a responsibility, to talk about this link between is and ought and should not be penalised for this. However, when doing so they have, I believe, to be very honest with themselves and others that they are taking on a more political role (I am not totally sure about hybrid roles, that needs more thought) and that this may have certain consequences. Now, as for the impact agenda, I think some people fear that it might force scientists to focus on the politics first and on the science second and that this might pervert the process of science, that is to say, that policy or politics will drive or shape science, not only in some parts of policy-relevant science, but more fundamentally, and that this might bring about a rather undesirable politicisation of science.

Hi, Athene.

I share your difficulties with interpreting just what Pielke means. See this exchange: http://physicsfocus.org/philip-moriarty-circling-the-square/#comment-6479

(It’s getting difficult to follow the various threads of the debates stimulated by the “Circling…” conference because they’re spread across quite a few blogs now. A little ‘disorienting’ perhaps, but no bad thing — it shows that the conference was successful in fostering a lot of debate).

I’d also like to pick up on the “Philip Moriarty wouldn’t touch impact with a barge-pole” comment. I can understand entirely why you might say this but I’d like to ‘nuance’ it just a little.

Like many of my colleagues in physics (including those in Physics & Astronomy here in Nottingham), I spend a considerable amount of my time as an academic scientist involved in outreach and public engagement. See, for example, Sixty Symbols and this recent article about Nottingham’s collaboration with Brady Haran in YouTube-based physics outreach. (Sixty Symbols formed the basis of one of our REF impact cases).

I am also exceptionally keen to take the research we do in the lab and expose it to as wide a public audience as possible. Brady Haran shares my enthusiasm for this. See The joy of a breakthrough (and this ). A more recent example is this: The Sound of Atoms Bonding .

So, in that sense, I am fully committed to maximising the impact of academic research.

What I am entirely opposed to, however, is the idea that socioeconomic impact — and, let’s be honest, as Brian Collins said in the opening keynote lecture for the Circling… conference (and as I’ve banged on about at length here ) what that really means is almost always economic impact — should be used to define the direction of scientific research.

Over the last few months I’ve had a number of e-mail exchanges and discussions with RCUK/EPSRC representatives re. changing the advice that the research councils give about impact. (Particularly this: ” Top Ten Tips ). These discussions have been very encouraging.

In the spirit of compromise and engagement (ahem), I have told those RCUK/EPSRC representatives that I will try an experiment to test the oft-repeated claim from the research councils that “Pathways to Impact” and “National Importance” are about much more than the potential economic value of the research. I will submit an EPSRC proposal which contains no mention of the potential economic impact of the research on this or that sector, nor of how it might “contribute to the economic effectiveness of the UK”. Instead, the Pathways to Impact and National Importance statements will focus entirely on non-economic impact in the form of public engagement and outreach.

I will blog about the writing, submission, refereeing, and panel review of this proposal over at physicfocus .

Philip

[…] the organisers Brigitte Nerlich wrote of her own slightly puzzled response to some of the debates here. She has also written a summary of the various responses […]

I wonder if we can go one step further and define natural science as that part of the sciences that can be neutral if we do it right. The other science are also valuable and should strive to be neutral, but when dealing with humans that is a lot harder.

That is a very good point! However, I would say, just because it’s more difficult doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be aimed for – being, of course fully aware of the limitations to such an enterprise!

This is a really good point, Victor.

Disinterestedness and neutrality are at the very core of what makes science special. If we remove those aspects then we’re not doing science.

At this stage in the game, expressing a preference for disinterested, neutral climate scientists seems very strange.

I don’t directly disagree with Victor, but would point out that the response of the political elite to the findings of climate science has thrown things off the rails to the extent that true neutrality isn’t really possible. As I said yesterday over at ATTP, what we have now isn’t “post-normal science,” it’s “normal politics.”

You should distinguish between disinterested neutral scientists and disinterested neutral science. The science should be neutral. Scientists are humans and being passionate about a topic is no problem. In fact it is what keeps us going. Even single scientists wanting to see a certain outcome is not a problem. It will likely make this scientist less productive, but he may also make a chance discovery with his stubbornness. The culture of the scientific community and the scientific method is there to make sure that on the long run the science that is produced is neutral, even with human scientists.

The climate “debate” in the media and on blogs is indeed mainly politics. You do not notice that much of that at universities and on scientific conferences or in the scientific literature. At least as long as you do not read an article by James Hansen or an article a climate “skeptic” managed to get past review. The latter often do so in obscure non-climatic journals, to avoid getting knowledgeable reviewers, thus such experiences do not happen that much by chance.

Brigitte – your thought experiment has been run in practice many times. The way you set it up excludes lay knowledge from the outset, the aspect that citizens in the communities might also know a thing or two which is relevant to the knowledge base of decision making.

But you are right in asking the question if people can trust the science when they are told it has value elements in it. One way of dealing with that question is to say that we do not find this problematic when we all share the same values (then we don’t even see them, as Roger Pielke Jr put it at the conference). If we don’t share the values we tend to get a controversy and ‘the science’ gets politicised and instrumentalised. Under these conditions science cannot play the role of the arbiter in political decision making, and scientists acting as advocates are running a risk (many will think twice if they should perform such an act, as both Ian Boyd and Roger pointed out). Are decisions then arbitrary? Tossing coins would be irrational for politicians, but catering to the interests of voters is not.

A hypothetical example. Somebody hears that people want to build a housing estate on a field near their house. They know that this field is the habitat of a protected species. They impart that knowledge (not political) to the local council in order to prevent the housing estate being built (political). Would you agree with that description??

I guess the list of protected species is the result of quite some negotiation, so would not be non-political. And the person who opposes the new buildings has probably many other reasons to object, but uses the ‘science argument’ because it deflects from self interest.

I wanted to make a point about local valid knowledge – probably bad example. However, I think my second point still stands. It was about what USE is being made about any type of knowledge (scientific, local, both, etc.), namely that the use of that knowledge is political rather than knowledge itself. I can of course not say whether my hypothetical example person believed the knowledge he or she had and then used to be scientific in nature or just ‘knowledge’ or whether he or she used it because he or she thought it was scientific.

I don’t think I did that in my thought experiment, or at least not intentionally. My imaginary policy maker asked the community to bring their wishes, worries and values to the table. Ok, I should have added knowledge but that was implicit in the list (I hope). Of course in any such imaginary consultation process various parties bring knowledge to the table or should be allowed to do so (look at any local planning application). In this post I was focusing in particular on the status of scientific knowledge in that process. And of course local knowledge too is not necessarily value-laden, biased and political, and should be treated on a par with scientific knowledge – it’s knowledge!

[…] myself observed this little skirmish and wrote two sort of meta-posts, one entitled Going round in circles, the other Science wars and Science Peace. Two issues discussed at the conference and then in blog […]