October 17, 2013, by Warren Pearce

Global science, local perspectives – how does climate change fit into policy priorities?

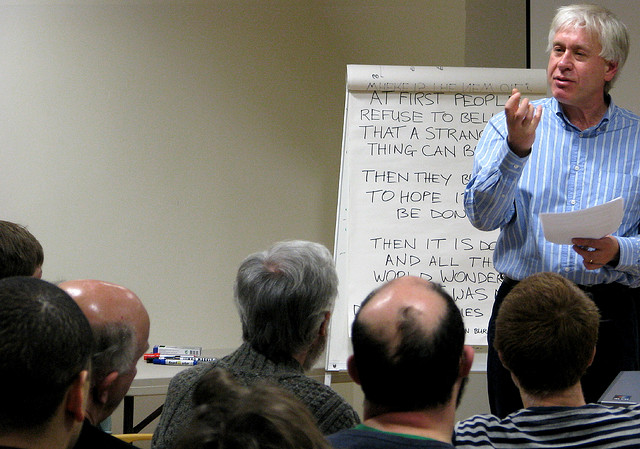

I present here a synopsis of a lecture I gave yesterday for year 3 undergraduates on our Climate, Science and Society module at University of Nottingham. The session was two hours long, which is rather a long time to listen to one person. So to ensure an engaged audience, I gave around an hour and a quarter over to a group exercise with the aim thinking about a rather thorny problem in public policy: prioritisation. Specialists in a particular issue are likely to promote the importance of their particular area as one in need of attention from policy makers. After all, they know the dangers and problems better than most. However, how do the politicians and other officials involve in the policy process weigh up these competing claims and decide what to prioritise?

To help with this, I show the first five minutes from Bjorn Lomborg’s 2005 TED lecture ‘Global priorities bigger than climate change’:

Policy prioritisation: a thorny issue

Lomborg’s view that climate policy represents poor value for money compared to solutions to other global problems such as disease, malnutrition, improving education etc has earned him plenty of ire from many quarters. (He explains his views later in this lecture, which is based on a fairly classical economist’s view of the world). However, his views on climate policy are of no consequence here. Rather, I focus on the valuable question he raises of how to prioritise policies, a task he sees as vital, but also as an anathema to politicians, who prefer to build coalitions of support. So I borrow Lomborg’s list of 10 global challenges and ask small groups in class to take up his challenge of naming their top three and bottom three policy priorities:

- climate change

- communicable diseases

- conflicts

- education

- financial crisis

- governance and corruption

- malnutrition

- population

- sanitation/water

- trade barriers

This is a great way of thinking about how climate change slots into the wider web of interlocking ‘wicked problems‘ which global policy makers face. Different arguments can be made for each problem being the ‘root cause’ of the others, or being so important and potentially dangerous as to exacerbate all the others. But like Escher’s staircase, it’s hard to know where the starting point should be. There is rarely agreement, so as well as asking for their priorities, I also ask students to clarify the criteria and assumptions which led them to make their choices. Of course, I don’t require groups to necessarily come to a consensus view – dissenting voices are allowed 🙂 The groups this week focused on governance and corruption as a key priority that was needed to precede many others. Also interesting was that climate change didn’t feature particularly high up *or* low down anyone’s lists.

Contradictions

After a coffee break, the second half had more of me talking about local interpretations of climate policy, drawing on my doctoral research into local meanings of climate policy, and that even when policy priorities are made explicit by political leaders this does not necessarily lead to action ‘on the ground’, where the messy compromises between competing interests highlighted in the previous exercise rear their head again. In fact, sometimes these contradictions can be found within a single person. So while in 2006 Prime Minister Tony Blair described climate change as “the single most important issue we face as a global community“, he also said that it was “impractical” for individuals to change their behaviour in the face of the problem. I show a memorable front page from The Guardian which described Blair as issuing a call to ‘carry on flying’ shortly after one of his environment ministers had launched an attack on budget airlines as “the irresponsible face of capitalism”:

Despite these contradictions, climate policy has become part of the legislative landscape – on the surface at least – with the passing of the Climate Change Act in 2008 which set non-negotiable targets for reducing carbon emissions (80% by 2050). This filtered down to local level, with many local authorities signing the voluntary Nottingham Declaration to tackle the causes and consequences of climate change, with carbon reduction proving to be the fifth most popular policy priority amongst councils in 2008 (p.324), proving more popular than long-established policy issues such as educational achievement, crime reduction and child obesity.

Apart from, not a part of, the environment

Despite this apparent enthusiasm for carbon reduction amongst local government, there are long-standing issues to overcome grouped around the idea of humans being “apart from, not a part of, the environment”. These can be split into three:

-

A ‘dominant social paradigm’ of nature and humanity being seen as a dualism, with the former existing primarily as a driver for the progression of the latter. Since the industrial revolution, this has become driven by the extraction of fossil fuels as cheap, powerful energy sources which have prompted unprecedented rises in living standards and prosperity, but which now hold the potential to change society in the future .

-

Climate change as peripheral. Here I draw directly on interview quotes from climate change policy managers, who all highlighted the difficulty in talking about climate change, describing it as a ‘turn-off’, something that other policy officials saw as ‘nothing to do with them’, or even as something that ‘the weird people over there do’. Note, these are the assessments of climate change managers themselves, observing the difficulties of introducing climate change as a meaningful concept within their organisations.

-

Climate change as extra-local. Climate change has emerged as a global, not a local, policy issues. This is partly down to the way the science has developed (Demeritt is highly recommended on how global circulation models have shaped climate politics), but also the emphasis on global negotiations and collective action which has dominated the political scene. This has led to a feeling of dis-empowerment for local areas: if the causes of the problem are global, why act locally?

Board meetings: climate policy struggles in action

Faced with these barriers, climate change managers realised they had a problem. Hence their preferred metaphor for their policy work as ’embedding’, meaning the insertion of one object (in this case, climate policy), into another object which displays resistance (in this case, the established policy landscape). One means of this was the use of board meetings which sought to bring together powerful section leaders within a local authority specifically to discuss climate change. These meetings proved to be a real-life site for the struggle over policy priorities.

In short, the meetings were not successful at driving forward policy implementation. A key symptom was the passivity of those taking part. So even if managers attended the meetings they frequently contributed little, with the climate change team doing most of the talking and receiving little (overt) challenge from other sections of the local authority. This was recognised both by the climate change managers and more senior directors, yet there was agreement that the meetings should continue. Why was this?

Rationality vs tradition

The meetings symbolised the contradiction at the heart of climate policy – trying to square the circle of the centuries-old tradition of pursuing economic growth and the wish to be a ‘rational actor’ and follow the advice of scientific experts. Rationality in society is a very important concept, which Peter Manning argues has dominated the rhetoric of organisations and accounts provided for decision-making. In particular, this was the case under New Labour, where policy as best seen as created in a ‘laboratory’. Politicians could not be seen as doing nothing in response to calls from scientists, NGOs, media etc – particularly in the stark terms in which the problem was often described. However, with this appeal to rationality, came targets which are arguably beyond capacity to achieve.

So making a choice between ditching ‘rationality’ and ditching ‘economic growth’ was a decision that appeared too dangerous for policy makers to take. There was a perceived need to maintain rational-scientific policy model while continuing to use fossil fuels to pursue economic growth. Instead, the meetings continued as a means of keeping the network of (dis)interested parties together, and holding open the possibility of possible resolution in the future. Unsatisfactory? Or an inevitable consequence of the uncomfortable problem of policy prioritisation which Lomborg sheds light upon?

A final thought

Could this have developed differently? Perhaps. There is some grounds for wondering if a Hartwellian approach to climate policy may not have resulted in policy officials attempting to wrestle between economic growth and decarbonisation. Focusing on causes of climate change other than carbon dioxide, such as black carbon, or using alternative measures, such as carbon intensity of economic production (ie how much economic growth do we get from each tonne of carbon emitted) may have facilitated greater progress as they offered a reduced threat to economic growth. However, they also carry the implication of missing the carbon reduction targets derived from the scientific literature. The question is, with the ever-present problem of balancing policy priorities, is this as much as we can hope to achieve?

Warren, you didn’t tell us how your students prioritised the issues?

I’m going to risk a a guess that the results did not match with this recent survey of public opinion in Europe, where environment and climate came out near the bottom of the list (page 19).

Thanks Paul. Not quite no. I only asked the groups to rank their top 3 and bottom 3. Climate didn’t feature in any bottom 3’s…and one out of the four groups had it equal 3rd. I asked them for a bit more reflection in the seminar today, and it seemed to be down to climate change being a different type of problem to the others. Longer term, less tangible etc So I then posed the question of whether it should be thought about in a different way to these more material problems such as malaria, conflict etc. There was some support for that. But nobody voiced the opinion that climate change was a *bigger* problem than any of the others. Of course, the whole exercise is a bit unfair, but that’s part of its beauty I think…

Not really a meaningful comparison Paul. Lomberg’s list addresses global challenges, and in Warren’s workshop is considered by a group of University students in an academic setting; the Eurobarometer list addresses personal issues that immediately and directly affect the surveyed group of Europeans. In a Europe with high unemployment, disrupted economies, price inflation, massive government debt, it’s rather unsurprising that these issues are on the minds of Europeans concerned about the effects on their personal lives.

In fact Warren’s students, being students, are in a rather privileged position (student debt notwithstanding!) of being able to take a more dispassionate and analytical view of issues of global challenges, and I expect that their views on the subject would be rather nuanced.

[…] Hiroshima bomb metaphor. He also wrote posts on issues related to the IPCC and climate sensitivity, climate change as a global and local issue, and climate change and […]