June 19, 2013, by Brigitte Nerlich

Extreme weather talk: Making climate public?

This is yet another in a series of blog posts where I try to show how one can use publicly available data (newspaper databases or Google Insight for Search) to observe patterns and shifts in public attention to climate change. Other posts have dealt with some first reflections on extreme weather, Hurricane Sandy, alarmism, carbon and energy discourses, and mitigation and adaptation.

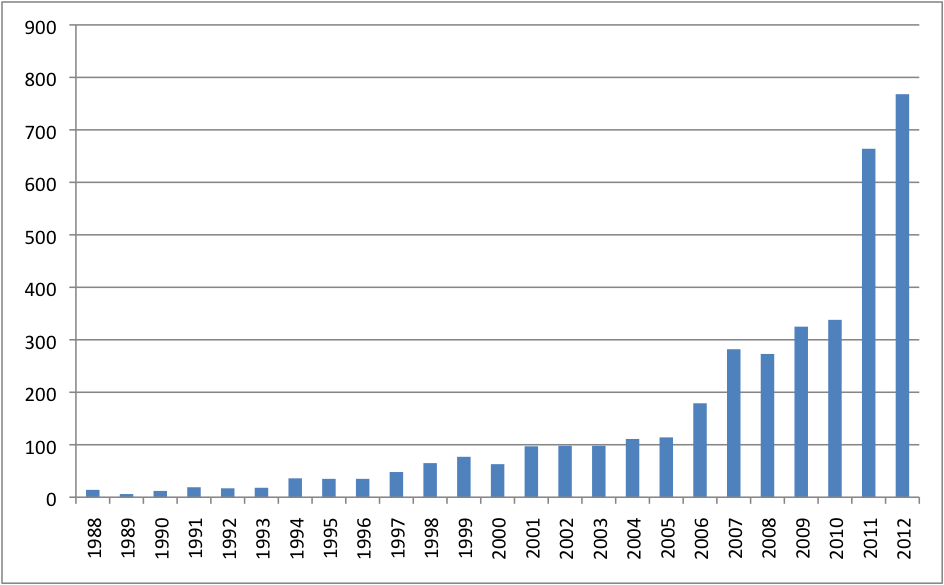

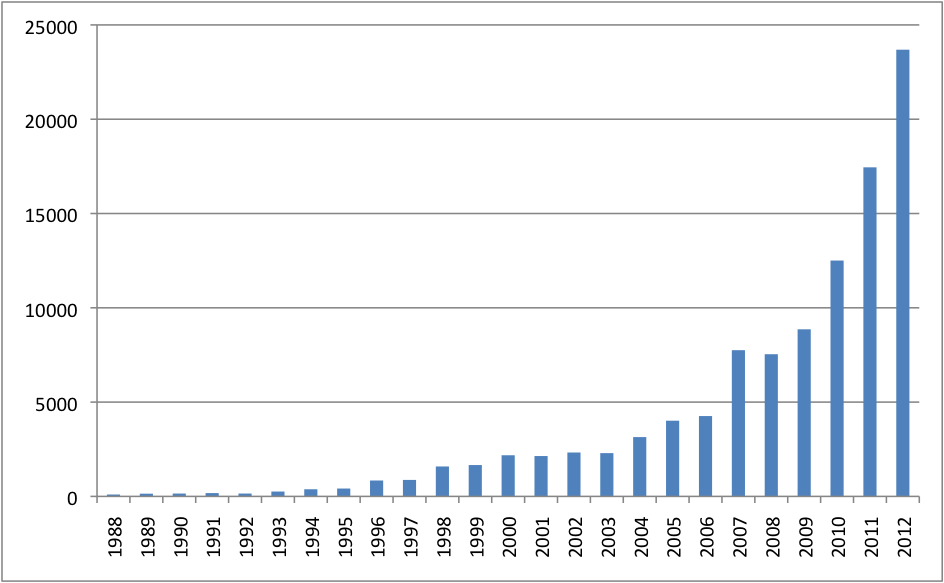

Mike Hulme once emailed me after one of my climate/weather blogs and jokingly said that my graphs always go up. And, lo and behold, in this blog they go up yet again. They chart a gradual increase in ‘extreme weather talk’ in the news which may be a subset of ‘weather talk’ (the topic of Mike’s most recent blog post). Surprisingly, this type of talk does not follow the same pattern as the generally decreasing climate change talk.

Extreme weather and climate extremes

Direct links between climate change and particular extreme weather events are difficult to establish and are normally hedged with caveats, as the process of unpicking signal from noise in weather data is extremely difficult. This has been the case again at a meeting arranged by the Met Office to talk about a series of extreme weather events in the UK. In this context, the climatologist Professor Sir Brian Hoskins said on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme that ‘Quite honestly we don’t know’ what has caused strange weather patterns in past decade (18 June). Despite this type of talk, media coverage about extreme weather events and possible links to climate change has been been increasing.

Observing reporting patterns in the media

As the following graphs show, the phrase “extreme weather” is gaining prominence in English media discourses together with the phrase “climate extremes” (although numbers here are much lower) (I did not search for odd, weird, strange, bizarre, freak or unusual weather). “Extreme weather” focuses public awareness on weather and can still be used without committing oneself to a link between any particular extreme event and climate change; by contrast, the phrase “climate extremes” makes are more direct semantic link between climate and weather extremes.

English language news reporting on ‘extreme weather’ has increased steadily since 1988 (Figure 1) when climate change became an issue of public concern and has been increasing quite substantially since 2007, the year of the IPCC report, after which, on other graphs, such as the regularly updated international media coverage graph by Max Boykoff, interest in climate change itself has, by contrast, been falling. The same is true, although with much smaller numbers, for ‘climate extremes’ (see figure 2). What many have called a ‘year of weather/climate extremes’ (2011) seems to have accelerated this trend even more, both for news on extreme weather and climate extremes, but particularly for climate extremes. This seems to indicate that associating climate with extremes may become more prevalent in the future and may (indicate a) shift (in) public opinion about climate change in general. An increase in extreme weather/climate talk might make efforts to keep extreme weather discussions separate from discussions about climate change more difficult in the future.

These increases can, of course be explained in several ways, one of them being that there is increasing ‘spin’ about climate change which uses extreme weather as a discursive hook.

Figure 1: “Extreme weather” in All English Language News (LexisNexis, High similarity setting)

Figure 2: “Climate extremes” in All English Language News (LexisNexis, High similarity setting)

The origins and persistence of climate change and weather discourses

When we look at the very beginning of the debate about extreme weather and climate, three early articles are of interest. One article in the New York Times from April 1987, which reports on research carried out by Dr. Irving M. Mintzer, a scientist with the World Resources Institute, points out: “Scientists say that if carbon dioxide and chlorofluorocarbons are allowed to accumulate in the atmosphere, they can keep infrared radiation from escaping into space and can cause a rise in temperatures around the world, leading to extreme weather fluctuations.” Another 1987 article in The Times talks about research carried out at the University of East Anglia. While referring to the scientists working there as “doomwatchers”, the article still ends on a warning note: “And the message from Norwich is chilling. If we know that we are destabilizing the world’s climate we must either change our ways or prepare for the consequence – whenever that might be.” As highlighted in my blog post on alarmism, positions have not shifted significantly since 1987!

In 1988 the United States experienced an extreme drought, that is, an extreme weather event, which (was used to) put climate change on the political agenda. The first article I found that uses the phrase ‘climate extremes’ is entitled (warningly or alarmingly or alarmistly) “Killer Air”. It was written for the Washington Post by authors also affiliated with the World Resources Institute, which was funded in 1982 and in 1985 helped “organize the first international meeting in Villach, Austria, on the build up of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere”. The article starts with the sentence: “The summer of 1988 won’t be quickly forgotten. First the record-breaking levels of smog pollution, triple-digit temperatures and drought. Now comes the news that ozone and acid deposits are killing trees and stunting the growth of crops across the country.”

These were the opening shots to the climate change debate in terms of pollution, the ozone hole and acid rain. These issues have now been largely resolved; what we are left with are “climate extremes” (also mentioned in the article), which are not. Climate change is mentioned as well and in surprisingly ‘modern’ terms: “A sensible pollution-control strategy must also recognize two other long-term energy-related problems: our increasing reliance on foreign oil and climate change.” The advice proffered sounds eerily familiar: “Solving our interrelated air-pollution, climate and oil-security problems involves enlightened, long-term energy planning.”

As one can see from the graphs, since 1987/88 noise about extreme weather, climate extremes and possible links to climate change has been increasing. At the same time, the language used to talk about climate and weather remains the same, as well as the stale-mate in climate politics. The question is: Will an increase in ‘weather talk’ in general and ‘extreme weather talk’ in particular disturb that relatively stable picture? These types of talk are of course not the same, as extreme weather talk can be seen as a sub-genre of catastrophe discourse, whereas weather talk can encompass a much larger variety of discourses.

Extreme weather: between symbol and reality

In the past, extreme weather events (droughts, melting glaciers, floods, hurricanes etc.) have been important as ‘symbols’ of climate change, but they were, in a way, more symbolic than real. An extreme and well-known example of such a ‘symbol’ was the depiction of Cologne Cathedral half-submerged by water on the front page of the German magazine Der Spiegel in 1986. This was supposed to illustrate the possible threat of sea-level rise brought about by climate change. Now German newspapers contain pictures of churches and cathedrals, submerged for real, in the context of the recent floods in Southern Germany. Such extreme events may make it easier to see weather as climate and extreme weather events as visible and visceral proof of climate change. This is already happening in the United States, it seems. Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication, pointed out that Americans are beginning to “connect the dots between climate change and extreme weather“. And as one science writer, Andrew Freedman, said: “All weather seems suspicious now“.

[This blog post, like the others mentioned above, is not only linked to the work carried out within the Leverhulme programme, but also to a systematic study of climate change a complex social problem supported by the ESRC]

Image: Hochwasser Passau 3 June 2013 (Wikimedia commons)

Hi Brigitte,

I saw Sir Brian’s soundbyte on the TV news and was very disappointed by it. So disappointed in fact that I posted a comment (below) on the official Met Office blog, which does not look like it is going to get a response…

Given the statistical analysis of historical data for the last 5 decades, ‘Perception of climate change’, by James Hansen, Makiko Sato, and Reto Ruedy published in PNAS volume 37, pp E2415–E2423 last year, can you please tell me why so many of the scientists meeting in Exeter today still seem to be so reluctant to admit that an increased frequency of more extreme weather – anthropogenic climate disruption (ACD) – is an inevitable consequence of a warmer atmosphere with more moisture in it more of the time?

Clearly, no single event can be attributed to ACD with 100% certainty but, as the above-referenced paper has demonstrated – in addition to an overall shift towards getting warmer – extreme events are becoming more frequent. Therefore, as per the abstract of the above-referenced paper:

Surely the time for equivocation on this subject has long since passed?

Hi

Thanks for your comment. I am neither a climatologist nor meteorologist. So in my blog I did not want to pronounce on issues that I don’t have the expertise to pronounce upon, especially given the reluctance of experts to do so. What I tried to show was that public discussion is getting to a point where this is becoming increasingly impossible.

[…] explored various aspects of climate change, such as extreme weather in the media (and here), the strategic use of ‘alarmism’ in climate change debates, public understanding of climate […]

[…] Extreme weather (2)? […]

[…] years ago I published a blog post on extreme weather. This showed that unlike media reporting on climate change, which has generally been going down […]