February 26, 2013, by Beverley Gibbs

Rebuttal to “The privatisation of science is not in the public interest”

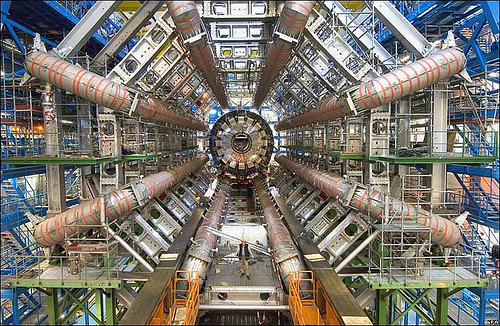

This post reproduces the main arguments I used when I argued against Alex’s motion that “The privatisation of science is not in the public interest” at the launch of the ‘Making Science Public’ programme at the University of Nottingham on 11th February 2013. Alex opened with his argument and I responded along the following lines. I conclude with some reflection our two posts. Video capture of these opening statements and the subsequent questions and comments from the audience, chair Adam Smith (from Research Fortnight/Research Europe), myself and Alex can be found here. Please, join in the debate! ———————————————————————————- Responding to ‘The privatisation of science is not in the public interest’ First, looking at the first part of the statement – the very notion of the privatisation of science is misleading. It assumes science has been mainly produced in the public sector and privatisation is a deviation from this norm, when in fact, it’s publicly-funded science that is the historical aberration. It is only war – particularly the Second World War and the Cold War – that firmly established scientific research as a public activity. Even now, for every £1 spent by Government, Research Councils and charities on scientific research, £1.67 is spent by private industry. Turning to the second part – privatisation is not in the public interest. This simply assumes that publicly funded science is (in the public interest). Privatisation is often judged on the basis of it being about outsourcing or a change in ownership that delivers profit to the private sector in order to transfer risk from the state sector, and that this is inherently harmful to the production of science. But there are many things about the government sector that make it inconsistent with the conduct of science – slow decision-making processes, risk-averse culture and a lack of access to capital, particularly for anything other than ‘Big Science’ by which I mean big labs, big staff, big kit and big budgets like the LHC at £7bn or the International Space Station – £80bn in the last 15 years. Projects that are difficult to regulate and highly elitist. What else does government mean by ‘science’? Warfare. 20% of government funded R&D supports military pursuits (a proportion which historically far exceeds that spent on health) – regardless of who owns the labs, Government wholly facilitates this market, firstly by funding research and then in buying the products (pdf on UK military R&D from SGR here). Third, the proposition assumes that we already know and share a view on what is the public interest – it must be whatever government does. But, how can this be known without mechanisms for meaningful social and ethical feedback? Are we to accept that one-off dialogues sponsored by a research funder are more meaningful than ongoing, live, dynamic public response to commercial activity that brings a concrete application to market, allowing meaningful judgment of its means and ends? How can we even start to explore the public good when publics are given nothing around which to articulate their voice? Fourth, it assumes that only the public sector can nurture autonomy and scientific freedom and that this entails basic research without concerns about impact. This linear model of innovation is at least 70 years old and really, we have known for over 30 years that it is not exclusive – applied technologies can lead to new science too. There are also plenty of examples of basic research funded within industry – the Dupont Experimental Station (Delaware) which produced not only a whole range of synthetics materials but synthesised crown ethers (earning Charles Pedersen a 1987 Nobel prize for Chemistry in the process), development of high temperature superconductivity at the IBM labs and the relationship between the Human Genome Project and Celera Genomics in the first human genome sequencing. Finally, the statement assumes a clear boundary between public and private. But this boundary is blurry, inconsistent, frequently breached and historically has been quite unstable. This does not mean that modern forms of private, commercial science are just like those of 100 years ago, merely that the boundary has never been clear. The National Physical Laboratory – the UK’s largest applied physics research organisation, and the UK’s first institutional binding of state funding and scientific research – has moved around this boundary in its 110 year history. First it was under the direction of the Royal Society, then a Government Department, an agency, a GOCO, and from 2014 looks set to be operated by a – shall we say – potentially less commercial consortium of universities and government. Context changes everything, and I suggest that broad brush arguments as to the name and ownership of science are less important than questions of degree, scope and scale. We are right to be concerned about the possible detrimental effects of private interests in science but really – is a political hand inherently better than an economic one? ———————————————————————– On reflection, I note three points from our posts that are related to where we chose to anchor our positions, and I hope teasing them out will be helpful in situating further debate. Firstly, to me privatisation is a question of economic organisation so I deliberately focussed on the question of ‘Who Pays?’. Much prevalent discourse (including Alex’s post) immediately associates this with the neoliberal political philosophy, in particular free markets. Whilst the two are closely associated, not all privatisation is exercised in order to construct a competitive market. Sometimes (as mentioned in my second paragraph) it is operational flexibility that is being sought and much publicly funded science is protected form market forces even when it is privatised. Secondly, quite clearly Alex locates science in Universities whereas I locate it outside Universities in research organisations and industry. This is an important distinction in our statements and both our choices play to the particular strengths of our arguments but realistically science is performed in all of these environments. I agree that the privatisation of research in Universities is problematic for a number of reasons – it undermines the public role of higher education (as Alex outlines) but also it distorts what I would defend as a perfectly legitimate external (free) market for more applied scientific research. Thirdly, I agree that markets are not the same as publics, but we cannot deny that publics are frequently formed around what the sociologist of science Michael Callon called the ‘economic spillover’. Only commerce can make science material enough to spark autonomous publics into forming on their own terms rather than as something envisaged by a policy-maker. Finally, I’d like to acknowledge the help of Dr.Sujatha Raman in ordering my messy opinions into something suitable for a 4 minute debate statement, and please do not assume this necessarily means she agrees with any of them.

This post reproduces the main arguments I used when I argued against Alex’s motion that “The privatisation of science is not in the public interest” at the launch of the ‘Making Science Public’ programme at the University of Nottingham on 11th February 2013. Alex opened with his argument and I responded along the following lines. I conclude with some reflection our two posts. Video capture of these opening statements and the subsequent questions and comments from the audience, chair Adam Smith (from Research Fortnight/Research Europe), myself and Alex can be found here. Please, join in the debate! ———————————————————————————- Responding to ‘The privatisation of science is not in the public interest’ First, looking at the first part of the statement – the very notion of the privatisation of science is misleading. It assumes science has been mainly produced in the public sector and privatisation is a deviation from this norm, when in fact, it’s publicly-funded science that is the historical aberration. It is only war – particularly the Second World War and the Cold War – that firmly established scientific research as a public activity. Even now, for every £1 spent by Government, Research Councils and charities on scientific research, £1.67 is spent by private industry. Turning to the second part – privatisation is not in the public interest. This simply assumes that publicly funded science is (in the public interest). Privatisation is often judged on the basis of it being about outsourcing or a change in ownership that delivers profit to the private sector in order to transfer risk from the state sector, and that this is inherently harmful to the production of science. But there are many things about the government sector that make it inconsistent with the conduct of science – slow decision-making processes, risk-averse culture and a lack of access to capital, particularly for anything other than ‘Big Science’ by which I mean big labs, big staff, big kit and big budgets like the LHC at £7bn or the International Space Station – £80bn in the last 15 years. Projects that are difficult to regulate and highly elitist. What else does government mean by ‘science’? Warfare. 20% of government funded R&D supports military pursuits (a proportion which historically far exceeds that spent on health) – regardless of who owns the labs, Government wholly facilitates this market, firstly by funding research and then in buying the products (pdf on UK military R&D from SGR here). Third, the proposition assumes that we already know and share a view on what is the public interest – it must be whatever government does. But, how can this be known without mechanisms for meaningful social and ethical feedback? Are we to accept that one-off dialogues sponsored by a research funder are more meaningful than ongoing, live, dynamic public response to commercial activity that brings a concrete application to market, allowing meaningful judgment of its means and ends? How can we even start to explore the public good when publics are given nothing around which to articulate their voice? Fourth, it assumes that only the public sector can nurture autonomy and scientific freedom and that this entails basic research without concerns about impact. This linear model of innovation is at least 70 years old and really, we have known for over 30 years that it is not exclusive – applied technologies can lead to new science too. There are also plenty of examples of basic research funded within industry – the Dupont Experimental Station (Delaware) which produced not only a whole range of synthetics materials but synthesised crown ethers (earning Charles Pedersen a 1987 Nobel prize for Chemistry in the process), development of high temperature superconductivity at the IBM labs and the relationship between the Human Genome Project and Celera Genomics in the first human genome sequencing. Finally, the statement assumes a clear boundary between public and private. But this boundary is blurry, inconsistent, frequently breached and historically has been quite unstable. This does not mean that modern forms of private, commercial science are just like those of 100 years ago, merely that the boundary has never been clear. The National Physical Laboratory – the UK’s largest applied physics research organisation, and the UK’s first institutional binding of state funding and scientific research – has moved around this boundary in its 110 year history. First it was under the direction of the Royal Society, then a Government Department, an agency, a GOCO, and from 2014 looks set to be operated by a – shall we say – potentially less commercial consortium of universities and government. Context changes everything, and I suggest that broad brush arguments as to the name and ownership of science are less important than questions of degree, scope and scale. We are right to be concerned about the possible detrimental effects of private interests in science but really – is a political hand inherently better than an economic one? ———————————————————————– On reflection, I note three points from our posts that are related to where we chose to anchor our positions, and I hope teasing them out will be helpful in situating further debate. Firstly, to me privatisation is a question of economic organisation so I deliberately focussed on the question of ‘Who Pays?’. Much prevalent discourse (including Alex’s post) immediately associates this with the neoliberal political philosophy, in particular free markets. Whilst the two are closely associated, not all privatisation is exercised in order to construct a competitive market. Sometimes (as mentioned in my second paragraph) it is operational flexibility that is being sought and much publicly funded science is protected form market forces even when it is privatised. Secondly, quite clearly Alex locates science in Universities whereas I locate it outside Universities in research organisations and industry. This is an important distinction in our statements and both our choices play to the particular strengths of our arguments but realistically science is performed in all of these environments. I agree that the privatisation of research in Universities is problematic for a number of reasons – it undermines the public role of higher education (as Alex outlines) but also it distorts what I would defend as a perfectly legitimate external (free) market for more applied scientific research. Thirdly, I agree that markets are not the same as publics, but we cannot deny that publics are frequently formed around what the sociologist of science Michael Callon called the ‘economic spillover’. Only commerce can make science material enough to spark autonomous publics into forming on their own terms rather than as something envisaged by a policy-maker. Finally, I’d like to acknowledge the help of Dr.Sujatha Raman in ordering my messy opinions into something suitable for a 4 minute debate statement, and please do not assume this necessarily means she agrees with any of them.

Nice exchange, too little time to respond in detail, but couple of thoughts:

I think the ‘state = risk adverse, private = risk seeking” argument is the kind of lazy essentialism you do a good job of challenging elsewhere. The private research hotbeds of science all seem decades past now – like Dupont and Xerox PARC and Bell Labs. At least three contemporary examples suggest that neolib caplitalism is highly risk adverse – Big Pharma’s focus on tweaking current drugs to escape expiring IP protection rather than on new drugs; the billions the ITC giants are spending on trademarking and litigating even the most basic interface controls; and the portion of venture funding that is now going into internet start-ups rather than applied science of the kind that might get us through the next century without societal collapse (something a new geolocation app isn’t going to manage). Meanwhile the only truly radical technological breakthrough of the last few decades is the internet, not only publicly funded (and were it not it would be propriatory and make Facebook look like open source utopia) but also through military funding. Military funding has been a huge source of risky, non-military applied science discoveries in the last half century, which you neglect to mention. This makes me pretty uncomfortable, but its something that needs recognition and consideration.

Also I think this is highly debatable/total cobblers: “Only commerce can make science material enough to spark autonomous publics into forming on their own terms rather than as something envisaged by a policy-maker.” Firstly its not true, as evidenced by ongoing public pressure to protect the NHS from private-captured policy makers. Secondly, what’s autonomous about an iPhone user base? Are you arguing that consumer desires are all intrinsic or authentic, that advertising and media plays no part?

Hi Murray, thanks for posting this comment over from Facebook where it started. Of your three core points I reckon Im going to take one on the chin, throw one straight back at you and elaborate further on the third.

– Firstly – about who is taking the risks here – this is a good point. If you think my position was essentialist Im going to direct you to Terence Kealey’s “Sex,Science & Profits” (2008). Kealy argues from long-term growth vs investment comparisons that publicly funded science displaces private sector investment so its no surprise that the “hotbeds of innovation are decades past”, given 20th century consolidations in public investment. Whilst his numbers are interesting, I am not about to support a wholesale retrenchment from the public sector in the expectation that the private sector will fill the gap – I think we’ve proved that doesnt work as a general principle! I also agree that using Intellectual Property law as an antry barrier is firmly associated with free markets and (I believe) even Kealey agrees it is destructive to the public good. So,Im taking that one on the chin. Kealey in action in video here http://archive.mises.org/13017/terence-kealey-science-is-a-private-good-%E2%80%93-or-why-government-science-is-wasteful/

– Secondly, that military technologies produce helpful spillovers. Well – anything would if you put much money into it, and it might do it without sustaining a big global death machine (if I can be slightly hysterical, but you get my point). In the UK it’s only in very recent years that we have spent as much on health research as we have on military R&D. Perhaps others would like to comment on whther they feel there is something inherently “creative” about military R&D that wouldnt get camparable results if you put the same vast pile of investment into space, health, food, climate etc

– Thirdly, on the isue of publics being sparked into being. On its broadest terms of course you are quite right and I could have used more modifiers. Publics emerge around all sorts of intangible, often quite distant issues (like extreme poverty for example). I think my point was that making something material makes a different – affected – public. These publics are still mediated (by NGOs, Governments, education systems, advertising etc) but actually I do think the mediation is more visible in the commercial sector.

(Could I also just add that use of IP is not restricted to the private sector by any means!!!!!). Perhaps someone could explain what justification there EVER was, or is, in publicly funded Universities exercising IPR. This is a genuine question.

Totally agree with you on military R&D. I don’t know if its only an American phenomenon resulting from the sheer scale of their military expediture (its the example that I know) but yes its a great shame successive governments have not considered other domains worthy of such investment. Perhaps there is something structurally unique about military R&D in that the sector is relatively independant of political micro-management in a manner than other sectors haven’t been? Given its purpose, its also relatively free of the need to demonstrate ‘economic impact’. Just an idea, not idea if its correct. I wonder if anyone has looked at how ‘efficient’ it has been in generating breakthroughs? It might well be hugely wasteful, but it had so much to waste it still managed sucess.

I think you have a point on the last one, in how easily groups self-form around commercial goods, but I wonder how much that is down to the fact that we live in a consumer society in which purchases are such important signifiers, and democratic engagement for many people amounts to little more than ticking a box every five years, if that. A self-fulfilling prophercy?

[…] in February 2013 (with a post summarizing the key note speech by Ulrike Felt and two posts by Bev and Alex on the debate entitled ‘The privatisation of science is not in the public […]