February 25, 2013, by Alex Smith

The privatisation of science is not in the public interest

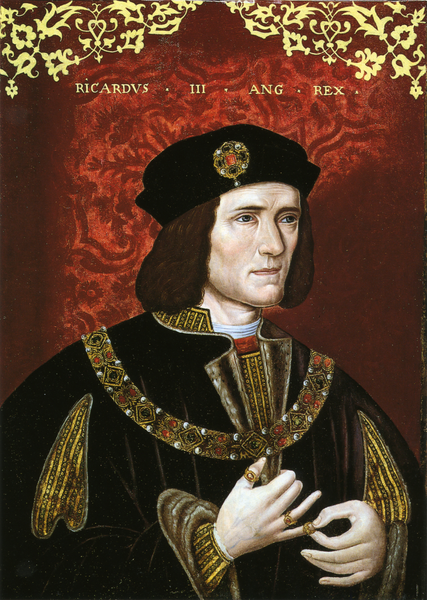

The University of Birmingham plans to close its Archaeology Department. But has the University of Leicester made Archaeology ‘trendy’ again following its discovery of the remains of King Richard III in a carpark?

This Blog post is a summary and more extended reflection on some thoughts presented as part of the ‘Making Science Public’ launch event. In the afternoon we kick-started a debate about issues related to the privatisation of science with two short talks by Alex Smith (tasked with speaking in favour of the motion as set out in the title of this post) and by Beverley Gibbs (tasked with formulating a rebuttal). For an overview of the whole day and to contextualise the discussion below, please read this blog post by Alasdair Taylor.

In the following Alex will summarise his thoughts first, followed by Bev’s rebuttal tomorrow.

One of the absences from our discussion of making science public has been the need for a political economy of contemporary funding for science research and teaching.

I want to focus here on the growing role of the free market in determining and shaping the funding of research and teaching as well as science policy more generally. I also want to sound a note of caution about what the neo-liberal turn to ‘transparency’ might offer as a remedy to the challenges facing those seeking to make science public.

Brigitte Nerlich highlighted the work of scholars who have written extensively about cultures of audit and transparency. But there is a sting in the tail for those who call for ‘opening up’ (public) science for all to see. Something that is ‘transparent’ is not so much something into which one can see more deeply, as if to properly apprehend that thing’s authentic self. Rather, it is something one sees through, to the other side, so to speak. It is ‘empty’, in a sense: translucent.

Is that what we mean when we call for science to be ‘opened up’? Do we mean we want to empty it, to see through it?

The value of transparency in audit culture makes it particularly appealing to those who advocate a free market solution to problems of public trust in science. However, as John Holmwood argued recently in the Harvard International Review (30 November 2012), markets are not publics. In fact, the practice of creating markets often undermines that of making publics, which primarily depends – as we heard from Ulrike Felt in her keynote address, quoting Michael Callon (1992) – on taking care of public institutions.

Many public institutions are in crisis in part because of the encroachment of the free market into virtually all realms of public life and the restructuring of the UK public sector along principles and values imported from audit culture and schools of business management.

We need to recognise, then, that if there is a crisis of public trust in science, this is not a crisis exclusive to science. It is not a problem unique to science or, dare I suggest, really about science and the practices it names at all. Rather, this is a general problem about the increasingly dominant role of markets in public life. It is also a specific problem of the privatisation of science.

Tuition fees

One of the starkest manifestations of this specific problem in recent years has found expression in the radical overhaul of the financing of British Higher Education that led to all public funding for teaching in the arts, humanities and social sciences being withdrawn for new students in 2012.

The burden of the full cost of teaching in these academic disciplines – many of which draw on powerful intellectual legacies and traditions that, until recently, were often regarded as belonging to a more broadly defined and inclusive idea of science than what it tends to represent in public discourse today – now falls on students, who pay up to £9,000 per annum in tuition fees.

But some academic disciplines have been protected (for now): the so-called STEM subjects of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. A public subsidy still exists for teaching in these subjects, a fact that helps reinforce a distinction between disciplines that are important to study and teach (STEM) and therefore deserving of some taxpayer support, and others that are not (the arts, humanities and social sciences).

For whom are STEM subjects important, and why? Much political capital is expended arguing for these subjects on the grounds that we in the UK, the EU and the West must continue to advance and innovate technologically if we are to claw our way out of economic recession and maintain our high (for some) standards of living.

This is clearly an argument about the value of STEM to the market. Indeed, it should really be an argument for why British business and industry need to dig deeper and invest more private money into the teaching of the science graduates they hope to one day employ and whom they hope will help their companies drive up profit.

It is less clear how valuable this argument for science, made in purely economic terms, is to the public, which is being asked to continue subsidising Higher Education teaching in a select few academic disciplines with taxpayer monies.

After all, improving the economic performance of our country will potentially mean little if all our citizens – that is, the public, in its widest possible sense – cannot enjoy an equal share of the fruits of that prosperity.

The privatisation of British universities

This is now an important question, following the privatisation of British universities – and science, as a consequence – through the back door. Universities now have a much-weakened relationship with the British public, on which they no longer depend for the bulk of their teaching budget.

They do, however, have a much-strengthened relationship to students as consumers who, in most subjects, pay the full cost of teaching through their tuition fees. This means universities and what they teach are dependent on market forces.

As a result, is it little surprise that the University of Birmingham plans to close its Department of Archaeology, which it deems ‘unprofitable’ in the market? (Perhaps it will think again, if Leicester has made Archaeology ‘trendy’ again following the discovery of the body of King Richard III in a car park!)

As a public, do we think Archaeology and the history of our ancient civilisation important?

If we do, why must we leave it to Birmingham or any other university to decide, on an analysis of market trends, whether or not there should be Archaeology Departments in modern British universities?

More importantly, by withdrawing all public funding for university teaching in most subjects, what right have we to argue that they offer courses and research we think our nation needs because we deem them to be in the public interest?

This situation fuels an elitist vision for British Higher Education and for science. Only those institutions that are profitable enough and sufficiently well endowed will continue as repositories of our intellectual and cultural heritage. And only those students wealthy enough to pay the high fees to attend those universities – not to mention the private schools able to secure them the best grades for getting into those top institutions – will have the luxury of benefiting from that heritage.

There is such a thing as the public (and it ain’t the market)

We elect Parliamentarians to debate and legislate in the public interest. This must mean committing public money and other resources to university teaching in all subjects and sciences – not just those that are considered ‘valuable’ by British industry. When MPs passed the recent Higher Education reforms that have led to the increase in tuition fees, they abdicated their responsibilities to the public in favour of the market.

The idea that there is such a thing called ‘the public’ that benefits from the existence of shared institutions in our society – institutions in which we all have a collective stake and responsibility to nurture – has a long history in the UK. Historically, we are talking about ideas of the ‘common good’, ‘the commonwealth’ (intellectual and cultural, not necessarily just financial) and ‘the commons’ – ideas we need to take seriously again.

Market values and neoliberalism reinforce and validate our worst habits and instincts, as individuals and consumers. These values do not belong in our institutions of higher learning and are antithetical to the idea of public science. They promote an exaggerated self-regard for one’s competitive advantage (in the marketplace, metaphorical and otherwise) and a belligerance and arrogance towards others, including a disdain for the intellectual traditions of other disicplines and sciences (remembering that broad definition, again).

What we need is a bold reaffirmation of the value of the public, not just in terms of its importance as a source of funding science research and teaching, but as representing a good in itself and an interest worth promoting. Market ideologies disable our potential to create and imagine publics in terms that cannot be reduced to monetary values of (privatised) benefit and cost. That is why the privatisation of public education and science is not in the public interest.

Caption for image: The University of Birmingham plans to close its Archaeology Department. But has the University of Leicester made Archaeology ‘trendy’ again following its discovery of the remains of King Richard III in a carpark?

[…] Public’ programme at the University of Nottingham on 11th February 2013. Alex opened with his argument and I responded along the following lines. I conclude with some reflection our two […]

[…] science that is equated with atheism, secularism and, increasingly, the market, as I have argued previously, is often imagined as a value-neutral practice focused exclusively on the ‘discovery’ of […]

[…] February 2013 (with a post summarizing the key note speech by Ulrike Felt and two posts by Bev and Alex on the debate entitled ‘The privatisation of science is not in the public […]