November 13, 2012, by Warren Pearce

Echoes of Climategate: focusing on uncertainty?

The ever-lively climate blogosphere was given an extra jolt recently by a new BBC Radio 4 documentary – Climategate Revisited. The programme assessed the fallout from the infamous publication of emails from the University of East Anglia (UEA) server, rather than attempting to adjudicate on scientific claims or the contents of the emails. The programme seems to have garnered a rare level of agreement across the spectrum of the climate debate, with praise coming from commenters at prominent sceptic site Bishops Hill for the programme’s balanced approach.

One interesting aspect raised in the programme was the effect Climategate may have had on the communication of uncertainty. UEA’s Mike Hulme noted that since Climategate, six percent of academic articles on climate science have mentioned ‘uncertainty’ in their abstract, compared to only three percent in the years preceding the affair. Comments by Fiona Fox, from the Science Media Centre, appeared to back this up. They are worth quoting in full from the programme:

Some of the really intelligent debates that have come out of Climategate have been those where people admitted, “I, as a scientist, didn’t want to be as open about the uncertainties” because of this war they were in. They were on a war footing and rather than thinking about communicating the best possible science in the most accurate and measured way they were also thinking over their shoulder about how it would be received by the sceptics. But they have to somehow work out a way of behaving as scientists rather than behaving as if we’re in a war. Because that would distort the best science. And that will be exposed.

So perhaps prior to Climategate, climate communications backgrounded uncertainties within the science as some scientists felt they were on a ‘war footing’, or maybe because they simply believed sufficient consensus had been reached. After Climategate, Fox and Hulme’s evidence suggests that scientific uncertainties have become more prominent which, in principle, would seem to be a good thing if one’s concern is to reflect the science as literally as possible. However, introducing more uncertainties also adds more complexity to messages which ultimately need to be succinct enough to be understood by a range of ‘non-experts’. If there is indeed a trend toward focusing on the uncertainties within climate modelling – in other words, the potential instability, rather than stability, of scientific facts – then what does that mean for the ways in which ‘climate change’ is understood in society? How does one determine which uncertainties should be part of the story, and which are left out?

My next post will examine how Climategate’s echo of uncertainty has been evident in the debates around Hurricane Sandy and its link to climate change, and how one magazine cover demonstrated how lucidity triumphs over literalism in public debate.

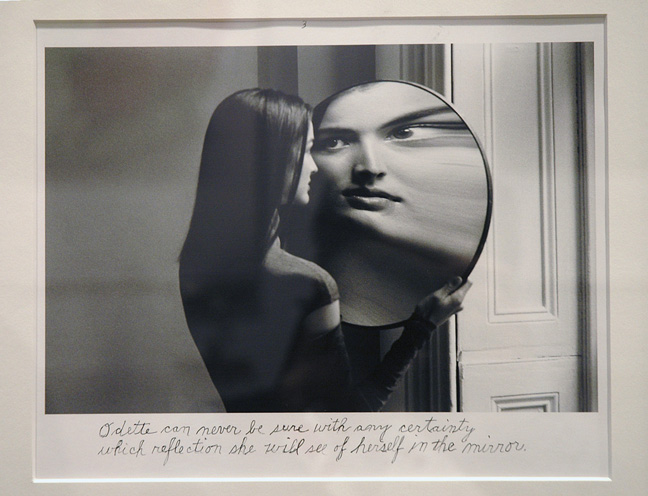

[Photo credit: http://www.flickr.com/photos/33255628@N00/5520938553/]

[…] at MSP reflected on comments in the BBC’s Climategate Revisited programme, suggesting that uncertainties in climate science have come to the fore in the years following the publication of scientists’ emails. By being more open about such […]

Yes, these remarks were interesting. Earlier in the programme she said “All of us felt like this is a critical moment and to some extent something changed and those journalists have since been scrutinizing climate science to a greater degree. And you know what? I think that’s good.”

But is this really happening? Are journalists asking scientists more probing questions than before? Or are they still lapping up every scare story they can find, without question, and adding their own exaggerated headlines? Some of the recent media stories, such as the Sandy one in your next post, or the recent scare that coffee is going to vanish because of global warming, suggest the latter.

[As an aside, knowing nothing about her, I have just looked up Fiona Fox and see that she is Director of the Science Media Centre, with apparently no science qualifications, and was a leading member of the Revolutionary Communist Party].

Thanks Paul. I agree, of course, that Fox’s comments need verifying and that the way in which language morphs between scientific paper, press release and media article is a key question. To take your excellent example of the coffee story, it looks like the Telegraph reflected the scientific uncertainty in the original paper pretty accurately, reporting the best and worst case scenarios. However, in the Telegraph the worst case scenario is reported far more prominently than the best case scenario – presumably as this is a better ‘story’. Also, there isn’t any critical angle to the reporting.

Thinking more widely, it may be that those articles emphasising uncertainty simply do not get picked up in the media, who may prefer stories containing established facts (or at least ones that appear to be established). This then brings us back to considering whether a threshold of certainty exists beyond which we can think of something as an established fact.

Re headlines, this is an issue across the media – I suspect that many headlines are not written by the journalists but by sub-editors. It’s another stage in boiling down the language from the initial scientific article into a handful of words, often with some metaphors thrown into the mix. Inevitably, this will cause some tensions, but not sure how it can be avoided. Of course, if the original source material is questionable that is a different matter, but is that more an issue of the peer review process rather than media reporting?

Yes, both the Telegraph and the Guardian seemed to pick out the worst case scenario of the coffee story, highlighting a figure of 99.7% that doesn’t seem to be in the original.

The other interesting point about the programme (particularly in the light of last week’s fuss about BBC bias) is the sceptic reaction to it. As you say, BH and also commenters at Climate Audit were surprised by the balance:

“Frankly, I was amazed. It was a lot better than I’d expected”

“The BBC did not push a specific agenda and was surprisingly fair to the sceptics”.

In view of this you might think that those towards the other end of the spectrum would be annoyed with the programme for giving the sceptics airtime. But Bob Ward, who was also interviewed, gave the programme this moderate endorsement:

“You can listen to last night’s good programme on ‘Climategate Revisited’ on BBC Radio 4 here: http://is.gd/AnWoTJ “

Thanks, had not seen the Climate Audit thread. Maybe it is worth thinking about the programme a bit more, as it seems to be a rare ‘good news’ story in terms of how it has been received. (Maybe not focusing on the science is the key!)

Re media reporting, Keith Kloor thinks nuanced reporting is out of fashion – although there are some good ripostes in the comments. Might be interesting to see the proportion of science stories in media which have some kind of critical edge to them, either through quoting dissenting voices, or from the author themselves. Perhaps it is less than in political stories, as scientists still(!) have higher trust levels than politicians…

[…] Echoes of climategate focusing on uncertainty – 2012/11/13 […]