May 18, 2012, by Warren Pearce

Atoms are not people: comparing the natural and social sciences

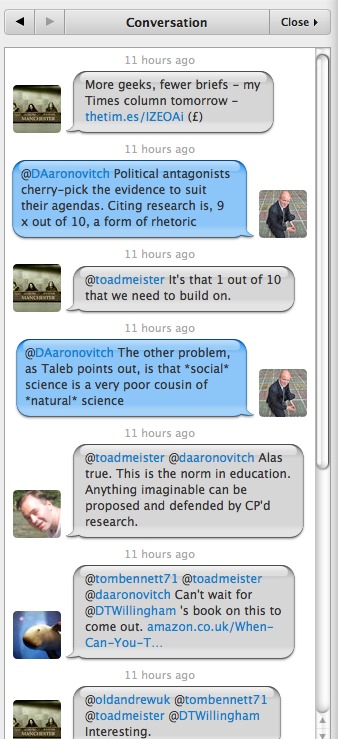

Following a Twitter debate this week on the utility of social sciences cf. natural sciences as a basis for public policy (see the above screenshot for some of the comments), I thought it might be time for a preliminary sketch of the differences between these two (very) broad areas of knowledge.

Following a Twitter debate this week on the utility of social sciences cf. natural sciences as a basis for public policy (see the above screenshot for some of the comments), I thought it might be time for a preliminary sketch of the differences between these two (very) broad areas of knowledge.

Is social science a ‘science’?

In 1853, Auguste Comte posited that all branches of human knowledge passed through three stages of development: theological, metaphysical and positive. Positive philosophy was the ultimate state for any area of knowledge, where observation and reasoning led to the discovery of laws. Comte regarded the natural sciences as having reached this state, whereas the social sciences were lagging behind – a position restated by Richard Feynman in this old Horizon clip.

Of course, “social science” is a term still in common usage today, which inevitably invites comparison with the natural sciences. Indeed many, if not all, branches of the social sciences have attempted to replicate scientific methods in order to achieve results that measure up to laboratory criteria such as validity, objectivity and generalisability (although these concepts can be interpreted differently across the very broad church of the social sciences). My argument is that in many cases these criteria are inappropriate for the social sciences, not because the latter is natural science’s “poor relation” but because they are fundamentally *different* in character. How so?

Laboratories vs ‘the real world’

In the natural sciences artificial, closed environments are created in laboratories. This can not (usually) be done in social sciences, the ‘outside world’ is an open system with multifarious potential variables to be measured. These open systems preclude the discovery of generalised ‘laws’ which can predict human behaviour across range of circumstances.

Why we need natural *and* social sciences

While natural sciences can help us understand the world, we need the social sciences to explain it. The pace of scientific discovery impacts ever more heavily on society, throwing up new questions for politics, religion etc. We need knowledge of the day-to-day language which people use and the personal, prior experiences with which they interpret their world, in order to show us how people come to diverse opinions on such discoveries (e.g. climate change, stem cell research, artificial intelligence). This is an argument made by a diverse range of thinkers such as Wittgenstein, Dilthey, Apel, and Oakeshott. People do not necessarily come to such opinions by means of a ‘rational’, scientific process.

Scientific laws can be disproved

The world of science is not as ‘fixed’ as it sometimes appears. Kuhn’s groundbreaking Structure of Scientific Revolutions uncovered the social processes inherent in practice of science. The Climategate emails provided a window into some of the less seemly language used by some scientists when discussing their field. Also, scientific results are always, by definition, provisional and waiting to be falsified. Significant assumptions which appear to have strong foundations can be disproved.

Statistics in the social sciences

The world of social science’s pursuing of scientific credibility has the potential to lead to the use of statistics to provide spurious certainty. How have the figures been calculated? Why have the researchers chosen to measure those variables rather than any others? This is not to repudiate the use of quantitative measures in social sciences; they have an important part to play. But they need to be treated with caution.

Craving certainty in an uncertain world

One facet of understanding all this is (wo)man’s aversion to uncertainty. The scientific method is seductive in holding out the promise of provable facts upon which we can base our decisions. A treatise in the nature of facts is beyond this post, but I would modestly propose that when the scientist takes off their white coat and leaves the lab, they walk into a world dominated by uncertainty and unknown unknowns. Atoms are not the same as people, and any attempt to think we can come to know the two worlds in the same way are not doomed because social science is in some way deficient, it’s because they are very different.

This is not to say that research in the social sciences cannot be rigorous and robust- far from it. Just that the self-awareness and careful sense-checking inherent to good practice in any research discipline can take many different forms. That, however, is a subject for another day…

Thanks to Beverley Gibbs from some critical comments on the first draft, prompting changes from my initial post published at http://realiseclimate.org/atoms-are-not-people-comparing-the-natural-an

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply