March 12, 2015, by Oliver Thomas

Censorship, gender and power: Fordyce and Catullus 58

Helen Lovatt considers the relationship between bowdlerising a classical text and broader questions of censorship.

Issues of free speech are still very much debated: recently the classicist Mary Beard was caught up in a twitter storm about no-platforming speakers at universities, in particular certain radical feminists whose views offend some in the transgender community. It is clear in that case that both gender and power were central to the debate: the power to express an opinion, the acceptance of the trans-gender community.

But does it matter whether the texts of Classical authors that we read are explained to us in full, or made more socially acceptable by cutting out the bits we don’t like? And why do people do it in any case?

I am teaching a worksheet in our Studying Classical Scholarship module on Fordyce’s 1961 commentary on Catullus. In this he omits 32 of the 116 poems which, he says, ‘do not lend themselves to comment in English’. It’s no surprise that most of the poems omitted relate to sexuality and the body. But it is interesting that active female sexuality is if anything more problematic than desire for boys.

When Fordyce comments on poem 58 he omits any discussion of the word glubit, which describes what Lesbia does to a large number of men, presumably sexual and derogatory.

When Fordyce comments on poem 58 he omits any discussion of the word glubit, which describes what Lesbia does to a large number of men, presumably sexual and derogatory.

Caelius, our Lesbia, the Lesbia

The Lesbia whom alone Catullus

Loved more than self and all his kin,

at crossroads now and in back alleys

peels (glubit) great-hearted Remus’ grandsons. (trans. Lee)

Fordyce falls for Catullus’ insult: ‘Catullus’ disillusionment is complete … the poem ends … with a sudden turn to the cold realism of ugly words.’ He goes even further by describing Caelius as ‘another of [Lesbia’s] victims’. Any woman who chooses who she wants to sleep with must be a prostitute and predatory with it.

The trial about the obscenity of the novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H.Lawrence took place shortly before the publication of Fordyce, in 1960. The prosecution made much of the fact that Lawrence uses obscene words, but also of the life, attitudes and character of the central character, Constance Chatterley. Perhaps what really offended about the book was not the transgressing of boundaries of class (symbolised by the vocabulary and dialect of Mellors) so much as the success of an active female protagonist in achieving what she wanted – not just sexual awakening, but a relationship in which she held the upper hand? Is Lady Chatterley a modern Medea, a fantasy of female power, with an inherited semi-divine status that allows her to fly beyond the expectations of reality?

For me, censorship is about knowledge and power. By restricting knowledge about Latin poetry and Roman sexuality to elite men who could read Latin and other foreign languages, Fordyce was reinforcing and helping to create structures of power. We still operate a great deal of censorship, particularly with regard to young people: is this really an act of protection, or an act of maintaining power and privilege?

Images:

Banner: Alexander Goudie, Christian Fordyce (Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow). © the artist’s estate / Bridgeman Images. Via BBC’s Your Paintings.

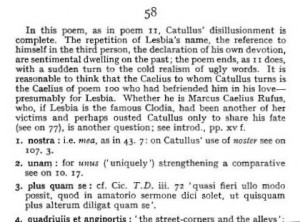

Right: part of Fordyce’s commentary on Catullus 58, scan from C. Fordyce, Catullus: A Commentary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1961).

March 12, 2015, by Oliver Thomas

Censorship, gender and power: Fordyce and Catullus 58

Helen Lovatt considers the relationship between bowdlerising a classical text and broader questions of censorship.

Issues of free speech are still very much debated: recently the classicist Mary Beard was caught up in a twitter storm about no-platforming speakers at universities, in particular certain radical feminists whose views offend some in the transgender community. It is clear in that case that both gender and power were central to the debate: the power to express an opinion, the acceptance of the trans-gender community.

But does it matter whether the texts of Classical authors that we read are explained to us in full, or made more socially acceptable by cutting out the bits we don’t like? And why do people do it in any case?

I am teaching a worksheet in our Studying Classical Scholarship module on Fordyce’s 1961 commentary on Catullus. In this he omits 32 of the 116 poems which, he says, ‘do not lend themselves to comment in English’. It’s no surprise that most of the poems omitted relate to sexuality and the body. But it is interesting that active female sexuality is if anything more problematic than desire for boys.

Fordyce falls for Catullus’ insult: ‘Catullus’ disillusionment is complete … the poem ends … with a sudden turn to the cold realism of ugly words.’ He goes even further by describing Caelius as ‘another of [Lesbia’s] victims’. Any woman who chooses who she wants to sleep with must be a prostitute and predatory with it.

The trial about the obscenity of the novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H.Lawrence took place shortly before the publication of Fordyce, in 1960. The prosecution made much of the fact that Lawrence uses obscene words, but also of the life, attitudes and character of the central character, Constance Chatterley. Perhaps what really offended about the book was not the transgressing of boundaries of class (symbolised by the vocabulary and dialect of Mellors) so much as the success of an active female protagonist in achieving what she wanted – not just sexual awakening, but a relationship in which she held the upper hand? Is Lady Chatterley a modern Medea, a fantasy of female power, with an inherited semi-divine status that allows her to fly beyond the expectations of reality?

For me, censorship is about knowledge and power. By restricting knowledge about Latin poetry and Roman sexuality to elite men who could read Latin and other foreign languages, Fordyce was reinforcing and helping to create structures of power. We still operate a great deal of censorship, particularly with regard to young people: is this really an act of protection, or an act of maintaining power and privilege?

Images:

Banner: Alexander Goudie, Christian Fordyce (Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow). © the artist’s estate / Bridgeman Images. Via BBC’s Your Paintings.

Right: part of Fordyce’s commentary on Catullus 58, scan from C. Fordyce, Catullus: A Commentary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1961).

Previous Post

Sappho’s BelovedNext Post

Charting the Spartan MirageNo comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first