March 5, 2015, by Oliver Thomas

Sappho’s Beloved

Doctoral student Harriet Lander introduces a case-study from her work on the history of translations of Sappho.

Solon, according to Aelian, asked his nephew to teach him one of Sappho’s poems, ‘So that I may learn it and then die’. This desire to know and understand Sappho’s lyrics has been a pervasive attitude from antiquity to the modern era, as her songs were filled with themes that engage people: eroticism, gods, myth, love and heartache. As time went on, fewer people were able to read her Aeolic dialect, but the appetite for her poetry did not waver and new, non-specialist audiences also wanted access to her work through translations. How these translated words have reached us through two and a half thousand years of scholarship is no simple journey of discovery.

Sappho’s poetry is partly famous for its depiction of desire between women. Fragment 1, the only poem to have been transmitted intact, is an example of this. But it hasn’t always been possible to read it as such: for centuries, the gender of Sappho’s beloved lay concealed in a textual problem.

In this poem the narrator, Sappho, prays to Aphrodite to help heal her broken heart as she is in the grips of an unrequited love obsession. Aphrodite flies down on a chariot drawn by sparrows to assist the lovelorn poet. She promises that the person whom Sappho desperately desires will pursue her instead of flee from her, give her gifts instead of refuse them, and importantly will love her even if the beloved does not really want to be with Sappho.

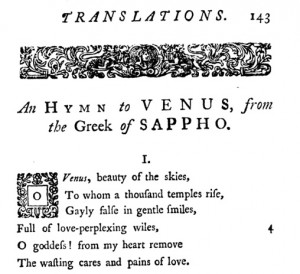

Sappho was first translated into English by Ambrose Philips in 1711. Philips assumed that her beloved was a man. Philips was aware of Anne Dacier’s earlier translation into French (1681), and Dacier also interprets Sappho’s darling as male – referring to ‘quel jeune homme je desirois’. Earlier still, Henricus Stephanus’ Greek edition (1554) contains no mention of the gender of the beloved, male or female. In the Greek manuscript tradition, three central manuscripts are corrupt where the gender of the beloved might appear and do not mention a gender, make any sense, or fit the metre of the poem.

Sappho was first translated into English by Ambrose Philips in 1711. Philips assumed that her beloved was a man. Philips was aware of Anne Dacier’s earlier translation into French (1681), and Dacier also interprets Sappho’s darling as male – referring to ‘quel jeune homme je desirois’. Earlier still, Henricus Stephanus’ Greek edition (1554) contains no mention of the gender of the beloved, male or female. In the Greek manuscript tradition, three central manuscripts are corrupt where the gender of the beloved might appear and do not mention a gender, make any sense, or fit the metre of the poem.

In 1843, Theodor Bergk produced the conjecture κωὐκ ἐθέλοισα, ‘even if she is unwilling’ for the only line of the poem where the gender could be revealed. He thereby constructed a reading of the poem that made sense and scanned. And subsequently his conjecture was confirmed by the rediscovery of a further manuscript from the twelfth century. The homoerotic desire in the poem was lost until Bergk unearthed it. Sappho, in fact, did write about her desire for women in this opening poem.

Those who have heard of Sappho may want to read about eroticism, gods, myth, love and heartache. But beneath any translation is a history of scholarship, without which corrupted passages of text would prevent us even from knowing about her objects of desire. The readers of her work can now understand what they are reading and how it came to be. They, like Solon, can understand it, learn it and then die.

Image credits:

Top: from The Works of Anacreon and Sappho. Done from the Greek, by several hands. (The Odes of Sappho done from the Greek by Mr. A. Philips), London (E. Curll & A. Bettesworth) 1713.

Bottom: from Ambrose Philips, Pastorals, epistles, odes, and other original poems : with translations from Pindar, Anacreon, and Sappho, London (J. and R. Tonson and S. Draper) 1748.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply