November 18, 2015, by Alex Mullen

Chorus girls – and boys

Lynn Fotheringham tells us about the creative challenges and opportunities of the Chorus.

In the Horrible Histories Groovy Greeks[1] theatre-show, a family of supposedly late-arriving theatre-goers are sucked into the action to learn about ancient Greek culture. They are informed that the Greeks had democracy, the Olympics and theatre: that the actors (all male) wore masks, violent action took place off-stage, and the Chorus were unlikely to break into ‘One Singular Sensation’,[2] but were “people who said the same thing all together”.

In ancient drama, the choral odes would have been danced and sung, but musicals like A Chorus Line[3] evoke the wrong kind of singing and dancing for Greek tragedy. The associations of the word ‘Chorus’ are one of the things that make tragedy challenging for a contemporary theatre company. As I went to one production after another of Greek tragedy in London over the last year or so, it began to feel as if the directors must have plotted together to present as many different approaches to the Chorus as possible.

The Old Vic’s Electra[4] and the Globe’s Oresteia[5] treated them as actors, dividing the lines of the odes among them with the odd bit of unison thrown in as a reminder of their collective identity. The Old Vic pared the Chorus down to three; the Globe broke with tradition by using men and women in the same Chorus. The Barbican’s Antigone[6] used the actors (male and female) as Chorus: the five actors other than Creon and Antigone emerged from the Chorus to play the other roles. The ancient sharing of all the roles among just three actors was also echoed when Antigone came back as the Messenger, announcing her own death.

The Almeida’s Bakkhai,[7] which stuck to the three-actor rule, also got close to ancient practice by having music specially composed for the new translation. It was no surprise to read in the programme that this Chorus included opera-singers as well as actors. There was disappointingly little wild dancing, though. In the National Theatre’s Medea[8] (see also here[9]) the Chorus included dancers, although this wasn’t immediately apparent. The first signs of dance looked like accidental twitches, gradually developing into a kind of choreographed thrashing, but much better than that description makes it sound: not ‘pretty’ dancing¾certainly not A Chorus Line¾but a powerful use of movement to reflect increasing tension, and perhaps Medea’s disintegrating sanity.

The most radical approach is to get rid of the Chorus altogether, at least as a group-entity, as in the Almeida’s Oresteia[10], although the play’s device of having an apparent psychiatrist-figure and adult Orestes looking back on past events has been compared to the Choral function of commenting on the action. The same theatre’s Medea,[11] also radically adapted to a modern setting, did use a Chorus, though their words had little to do with the original text. Their costumes partly echoed Greek robes, but they clearly represented modern gossiping neighbours. Rather than reciting in unison, they spoke at random and in non-sequiturs, creating a buzz of noise representing the thoughts of ordinary people in distinction to Medea’s extreme reactions. It was a fascinating approach which I’d love to see used again. From what I’ve read, Manchester Home Theatre’s Oresteia[12] had a vast Chorus made up of members of the community, which also echoes ancient practice in another way. It has been wonderful to see so many creative responses to the challenge of the ancient Chorus.

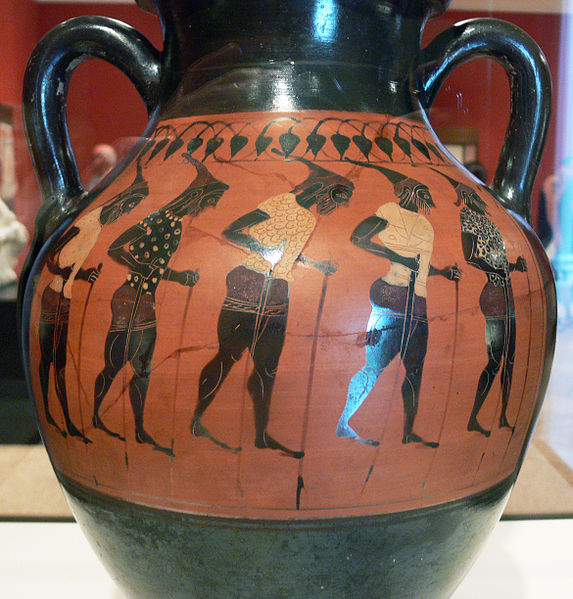

Image: Storage jar with a chorus of stilt-walkers, Getty Villa, (c) Remi Mathis, licensed via Wikimedia Commons

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply