October 11, 2013, by Brigitte Nerlich

Do online user comments provide a space for deliberative democracy?

This is a guest post by Luke Collins who is working with Brigitte Nerlich on an ESRC funded project dealing with climate change as a complex social issue. Yesterday, he gave talk about his research to an interdisciplinary audience attending the Institute for Science and Society/STS PG seminar series.

The internet has enabled traditional newspaper organizations to distribute their publications online, as well as offering the opportunity for the readership to respond, most commonly in the way of user comments. Some hope that online journalism creates spaces for more deliberative and democratic engagement with news stories. Though journalists may remain the ‘authority’ on online content, with online resources we find the greatest potential for that shift from journalism as a ‘lecture’ to a ‘conversation’ and the opportunity for discourse as a fundamental principle of democracy.

Some scholars, however, question the impact of reader comments on realising the ‘deliberative democratic potential’ of online discussion. Furthermore, rather than fostering critical debate, some suggest that the space for freedom of expression has led to polarized and extreme views. Painter observes that particularly in the U.K. and the U.S., “climate change has become (to different degrees) more of a politicised issue, which politically polarised print media pick up on and reflect”. Popular Science has elected to shut down user comments altogether. There is also, of course, the issue of moderation. This suggests a need to examine the potential for deliberation in online discussion threads and whether they really do offer spaces for democratic debate.

User comments

The wealth of comments which follows articles poses methodological challenges social scientists and linguists studying them. Previous research looking at online user comments has generally been based on manual content analysis and as such has been limited in the scope with which it can represent online debates. Corpus analysis is a systematic and automated process based on the statistical analysis of word frequencies which allows us to process larger datasets more quickly and more objectively. In turn, this allows researchers to explore much broader questions in relation to online journalism across larger datasets. Some scholars dealing with climate change issues have begun to make use of corpus linguistics to study online reader comments.

The corpus analysis tool WMatrix3 that I used for this analysis has a built-in semantic categorisation function, which allocates each word of the data to a category based on its semantic meaning. The software tool is then able to determine which are the most key categories based on a statistical comparison with a normative corpus provided by the British National Corpus (BNC) as a representation of ‘normal’ language use. This allows us to make broad comparisons between user comment threads about what are the key themes of the discussion.

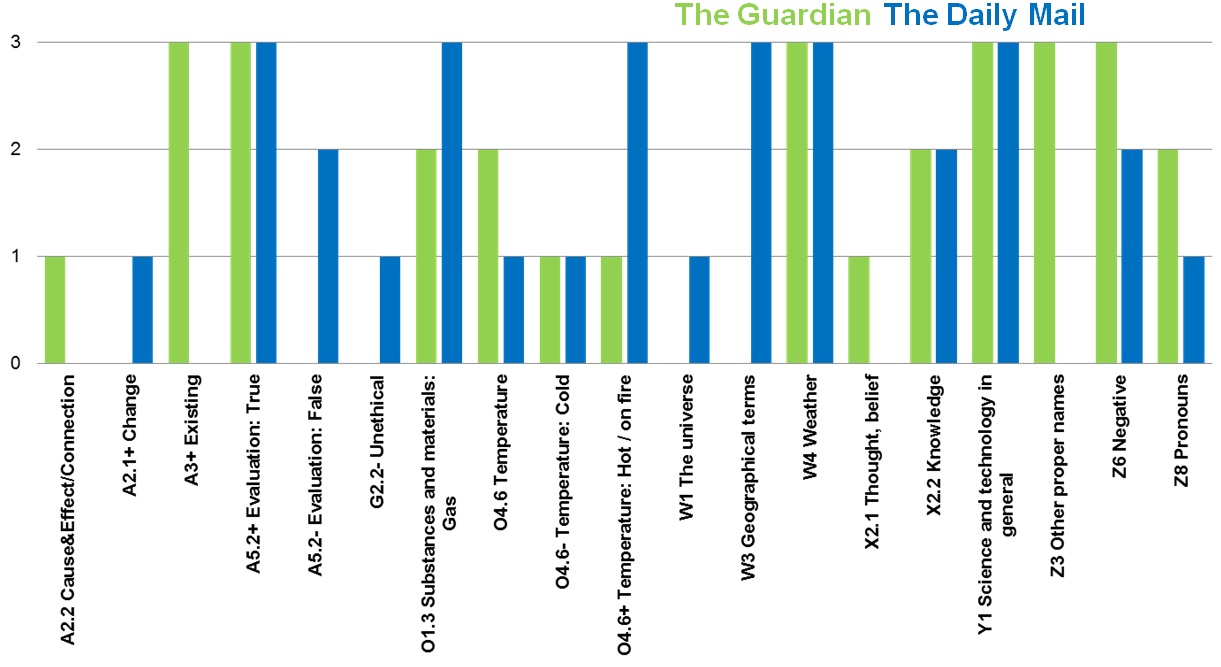

Taking, for example, three articles on climate change from both The Guardian and The Daily Mail online which received the highest number of comments, the graph below shows which semantic categories made up the ‘top 10’ for each thread:

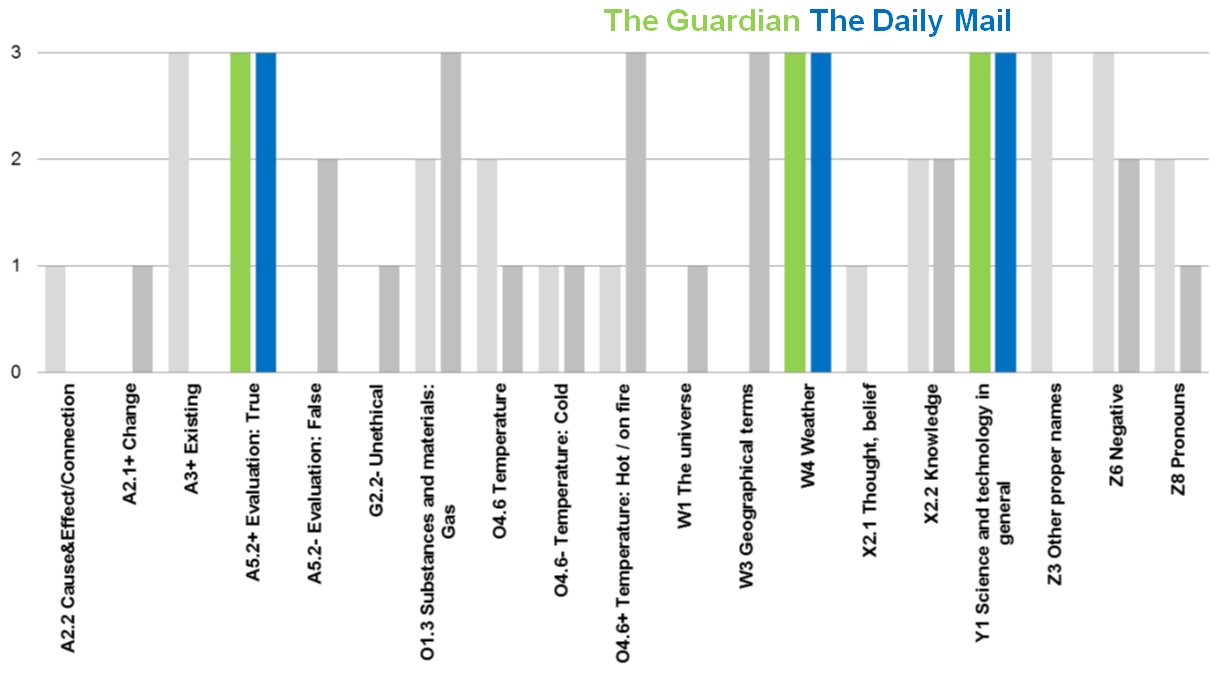

In all three discussion threads from The Guardian and all three from The Daily Mail the categories of ‘Evaluation: True’ (incorporating words such as ‘proof’, ‘evidence’, ‘fact’, ‘truth’); ‘Weather’ (words such as ‘climate’, ‘weather’, ‘snow’, ‘wind’); and ‘Science and technology in general’ (‘science’; ‘scientific’; ‘thermodynamics’) were prominent:

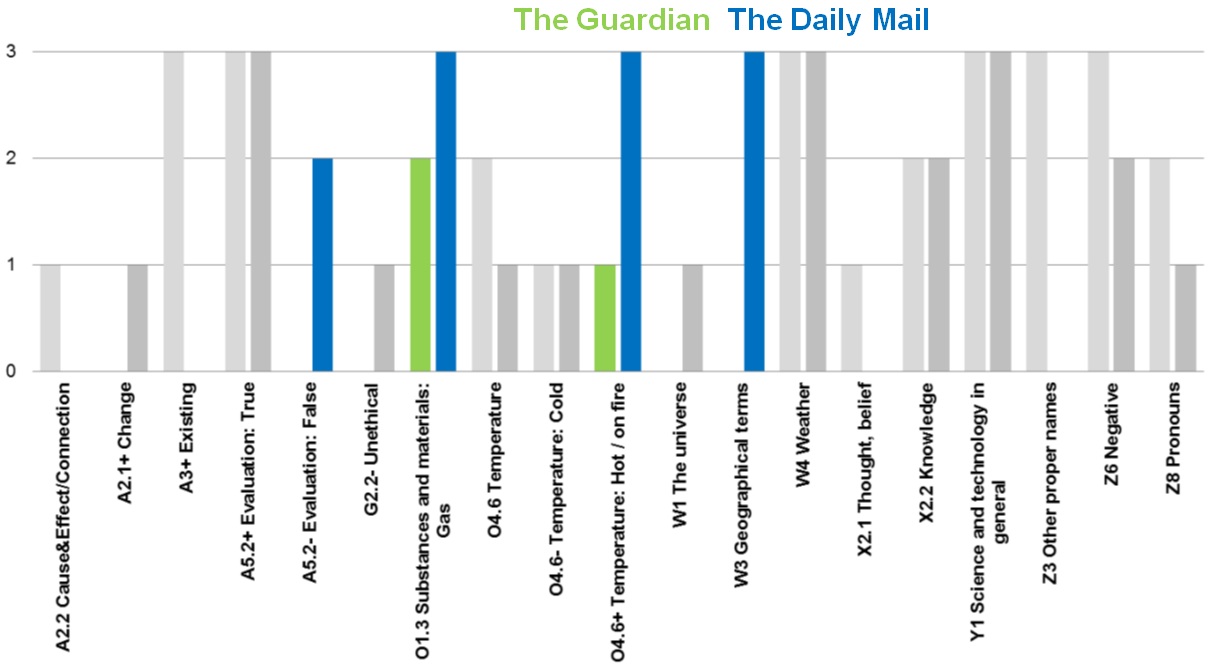

Those categories that were prominent only in the discussion threads taken from The Daily Mail were ‘Substances and materials: Gas’, which largely consisted of references to CO2; ‘Geographical terms’ and ‘Temperature: Hot/On Fire’, which together accounted for frequent use of the term ‘global warming’; and ‘Evaluation: False’, which in contrast to the category incorporating words of ‘truth’, ‘proof’ and ‘evidence’, was made up of terms such as ‘lies’, ‘hoax’, ‘false’, ‘deception’ and ‘misleading’. This category was not as prominent in the discussion threads taken from The Guardian.

The implication is that much of the debate is based around the available scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change, which is perceived by some to be manipulated and part of a ‘hoax’. Those categories which were prominent only in the threads taken from The Guardian were ‘Existing’ (including the words: ‘is’, ‘are’, ‘being’) and ‘Negative’ (‘not’, ‘nothing’, ‘neither’) which represent a pattern of claim and counter-claim/rebuttal, such as ‘This is not credible’. This in the very least is dialogic in that it shows engagement with claims that have been made in the discussion. As flat-out denial however, there is little potential for mediation. This level of engagement was also manifest in the prominence of the category ‘Other proper names’, which was largely made up of the monikers used by users in the thread as commenters made reference to specific users and their comments.

Users

One important thing to consider in such discussion threads is the continual presence and contribution of particular users and consider the 1-9-90 principle. In the discussion threads referred to here, it was often found that 8-10 users would be responsible for 20% of the comments and that these same users were the most prolifically referred to in the comments of others. Two-thirds of users made only a single comment. This is indicative of a limitation on the ‘democratic potential’ of such online spaces, which appear to be dominated by a small number of ever-present users. However, researchers have found that high posters showed a “marked preference for a dialogical mode of address”, which would suggest that such users encourage deliberation, or in the very least that they acknowledge the contributions of others.

‘Dialogic expansion’ and ‘dialogic contraction’

To examine the potential for deliberative and democratic engagement we can refer to the language of intersubjective stance and the ways in which individuals invite or inhibit deliberation through aspects of their discourse. We can refer to ‘heteroglossic engagement’ which describes utterances which engage with dialogic alternatives. Recognising that individuals communicate their stance – or their association around a particular idea or principle – through discourse we can distinguish between the strength with which they associate themselves with that idea (modality) and the potential for alternative ideas to be considered. At one end of the spectrum we find the bare assertion: the statement as if ‘fact’ that makes a simple claim in simple terms. More often however, utterances consist of discursive features that – to some degree or another – recognise that the statement exists amongst a multitude of alternative positions. Within the ‘heteroglossic’ there are those linguistic resources which are seen to be ‘dialogically contractive’ and those which are ‘dialogically expansive’.

Whether a statement is ‘dialogically contractive’ or ‘dialogically expansive’ is largely determined by stance indicators, including modal verbs ‘can/could’, ‘may/might/must’, ‘shall/should’ and ‘will/would’. We can see how the more uncertain terms, ‘may’, ‘could’, ‘might’ more effectively encourage the consideration of alternatives than the assertive ‘will’, ‘shall’, ‘should’. The use of modal verbs in this way not only indicates the individual’s attachment to a particular stance and the potential to ally themselves to new alternatives, but also welcomes alternative voices or propositions from other interlocutors.

A statement such as ‘if it could be proven that’ is speculative, it entertains an idea and as such sets a precedent for other contributors to discuss in terms of possibilities. This kind of expansion is necessary for the introduction and development of new ideas, of alternative viewpoints and for learning.

In contrast, a matter-of-fact statement such as: “Extreme (cold) weather won’t falsify AGW”, regardless of whether it is agreeable or not, offers little encouragement to deliberate. This kind of analysis demonstrates that there are multiple opportunities for commenters to negotiate the expansion or contraction of the debate, that is, to open it up or close it down. In reality, individuals will offer both dialogic expansion and dialogic contraction alternatively across sentences and we will always want to make assertions in certain terms. But to encourage a culture where uncertainties are part of the discussion at the level of discourse encourages interaction and deliberation.

Unfortunately many sites moderate, pre-moderate or simply delete comments that don’t align with the author’s views. The data analysed is therefore not necessarily representative of the commenting population.

Yes, that’s certainly something we have to consider.

Yes indeed – there are limitations here, as with any study. Deleted comments are definitely an interesting topic though, under-researched I think (although, of course, the data is considerably harder to obtain)

Are you expecting to have your article published in English? Or shall I wait for the film version and hope it has subtitles? I thankfully gave up at ‘heteroglossic engagement’.

By then you’d spent at great deal of effort saying

1. Some people comment a lot, others less so

2. Some people invite discussion, others don’t

which should have been obvious since humanity invented speech and other forms of communication.

I often think that a lot of academic ‘work’ is pretty pointless — simply making work for idle brains – but this is surely among the most trivial ever.

Every discipline has a certain terminology. Applied linguistics is no exception. In this case the use of a term that is accepted currency in that discipline was made perfectly clear and was surrounded by plain English.

Latimer, sorry that you have been disappointed (again!) Of course you are right in your basic point re commenters and their comments, but I think it’s interesting to try and work out the means by which this state of affairs comes to pass, and what the implications might be.

A modicum of technical language is sometimes to be expected. I might be similarly frustrated if I had to work out what Saybolt Universal Viscosity meant, but I guess this is the cost of reading outside one’s area sometimes.

Latimer, you gave up? You didn’t read the linked 25-page paper on the subject? I think “heteroglossic engagement” means “different people talking to each other” (e.g. what you are engaging in here).

I sometimes wonder if there is a need for another research programme, “Making Sociology Public”? 🙂

I thought Luke’s talk was quite interesting, particularly the question of whether such fora promote constructive discussion or merely increase polarisation. Compared with the seminars I am used to it seemed a bit lacking in conclusions, but I think that’s partly because it is work in progress and partly the arts/science style difference.

There was an interesting question at the end (which I was thinking of asking myself) as to whether these methods can be used to track changes over time. Is the debate changing, or are people arguing over the same points as ten years ago? Is climate scepticism increasing in online comments, as some opinion surveys have suggested?

Glad you enjoyed the talk. The issue of changes in debates over time (what linguists, since the time of Ferdinand de Saussure, founder of general linguistics, call ‘diachronic change’;)), is really interesting and we’ll try to delve into that a bit more.

Hi Paul. Yes, it would be really interesting to try and track this over time. It might be somewhat imperfect, because of course the commenters are reacting to different articles each time…

…or perhaps they are not. Some of the research suggests that many commenters tell the same stories in the comments repeatedly, no matter what the material is ‘above the line’. This sort of behaviour is often bemoaned online, but it’s actually not that different to a lot of speech in real life. So maybe a longitudinal study may provide some interesting data.

Yes, also this is very much work in progress – especially re finding methods with which to process huge volumes of data in a meaningful way.

You made a good point after the talk regarding searching for good comments online. Mentioning no names, but some blogs have some very interesting comments buried amongst mountains of much less interesting contributions. One could see how these types of methods could help find comments which invite more interaction, which blog owners may wish to display more prominently. This could also help to invite new commenters into the fray. From my own experience I know quite a few people with interesting things to say on climate change, but find the online space pretty intimidating.

Paul/Warren/Brigitte

Please remind me exactly what the point (if there is one) of this whole exercise is supposed to be.

You’ve waffled about a bit to draw some entirely unsurprising conclusions by reading some stuff that other people have written on blogs. And you’ve thought of some other stuff that you think might be ‘interesting’ among yourselves.

No doubt somebody will write a paper about it and get a tick in the box to supervise a new generation who will self-perpetuate a further round of trivial conclusions about unexceptional stuff..and so the merry-go-round of futility will continue.

But I am desperately reminded of a chum who claims to be never happier than when rearranging his sock drawer. And whether it is wrapped up in fancy language like ‘pedamental garment storage reallocation activities’ or ‘heteroglossic engagement’, both his wet Sunday afternoon hobby and your work remain no better than very lightweight pastimes.

Have you really – as supposedly clever grown adults – got nothing better to do with the rest of your working lives? Try getting out of the ivory tower occasionally. There’s a big wide world out here. Much more fun. And some of it even has a point.

Hi

From the dawn of time humans have tried to find patterns in the world in order to understand it better; that’s what science does; that’s what applied linguistics does. Sometimes this is difficult, when the volume of data is too big to just look and see. The issue of increasingly big data is one we have to grapple with in particular in our modern era of digital communication. We are interested in finding patterns in user comments in order to find a way out of a communication deadlock that has developed especially in the context of climate change. We also want to test out new tools that allow us to generate meaning, understanding and knowledge from big data sets. In the end, I suppose, we do this to find ways of making communication between people, especially those talking about climate change, easier, better, possible; and to provide commenters and moderators with insights that can become guides to ‘moderation’.

Latimer has expressed to me that he clearly thinks that we’ve wasted money on climate research which, according to Latimer, has produced nothing. Here he seems to think that research into communication is a waste of time and, based on a Twitter comment, he doesn’t think the Americans withdrawing from Antarctica for the season is a particularly big deal. I had, initially and maybe unfairly, assumed that Latimer objected only to the results of climate research, but it seems that he simply objects to research in general. So commendable consistency really 🙂

Thanks Wottsie

When I’m in need of an amanuensis, I’ll advertise widely for one. As an equal opportunity employer, you will, of course, be welcome to apply – as will everybody else.

Though I should counsel that you will be unlikely to pass the all-important ‘rapport’ test. I’d prefer somebody who demonstrates critical thinking skills and presents evidence to support his case. Yes men who merely parrot the approved party line are ten a penny.

Thank you all for your interest and your comments – this exercise does become something of a meta-analysis: analyzing the comments on the analysis of comments :S To that effect, I wonder if Latimer Alder recognizes the irony of their comments, which will provide a wonderful example of ‘dialogic contraction’ for future talks!

As has been said above, one of the aims for this work was to develop one way of coping with online discourses, since so much of the information on and discussion of any social phenomenon takes place online.

In addition to this, I was particularly interested in the perpetuation of the disparate views on anthropogenic climate change – which would of course require a longitudinal study – when there didn’t seem to be the scientific knowledge to ‘solve’ the problem. In other words, it was not a case of having the right information but rather the understanding of the available scientific knowledge.

To provide a more topical example, it is worth thinking about the terms – and the attention given to the terms – used in such documents as the IPCC report, where ‘likely’, ‘very likely’, ‘extremely likely’, ‘95% likely’ etc. etc. reveal an expectation to communicate in (arbitrarily) certain terms.

Luke

Why does anybody need a ‘way of coping with online discourses’.

Are there really people who can’t cope? Who? What evidence do you have? How big a problem is it? If it is a problem, how much blood and treasure should we spend to solve it? Please show your working.

Please find a moment to reply if your sock drawer will allow.

I’m sorry, let me clarify – the issue of ‘coping’ is in relation to researchers managing the sheer size of data afforded by the internet and online spaces. For any aspect of communicative analysis it’s undeniable that online spaces offer a vast and real representation of the ways in which people communicate with one another.

Perhaps it would be more understandable to locate the work as an exploration of a form of rhetoric. Now I know that you yourself are familiar with rhetorical constructions as you so deftly employ them in your comments above. But I’m sure you can appreciate that an attempt to belittle someone’s contribution to research based on an anecdotal assessment of an acquaintance who expressed enjoyment in what we might consider to be a mundane and insignificant task offers little to the scientific debate. Would it be of interest to you to know that in that respect, the discussions on the Daily Mail are not so different to those conducted on University-hosted blogs?

The value of this is not specific to the discourse around climate change – in fact it is a more general practice of the reflexive researcher, acknowledging their intersubjective role as a particular kind of scientist, responding to a particular kind of initiative and disseminating to a particular recipient. The question of ‘certainty’ is at the heart of the climate change debate (certainly, in online discussion threads) and I would suggest you consider what it means to be ‘95% certain’ for example. Here, surely, is an arbitrary quantification of ‘certainty’ which operates as rhetoric but is very much the main talking point (as apparent in the media) of the latest IPCC report.

Even if the discourse of the average media consumer offers nothing to the scientific debate the climate scientists themselves who contribute to such reports are subject to the same intersubjectivity and perhaps their ‘heteroglossic engagement’ would be something you consider to be valuable?

Let me, too, clarify.

I am not particularly belittling your personal contribution to this ‘research’. I am belittling the whole idea that what you and your colleagues are doing is at all a good use of your time and talents and my funding. And so far you have advanced absolutely no reason why it has any useful purpose.

I used the sock drawer analogy deliberately. It is a purposeful activity, it takes time and a certain amount of concentration to do well. But ultimately it is of zero consequence. Please suggest some reasons (if indeed there are any) why your choice of study is of any more use than arranging socks. You could consider the following question in outline:

‘At the end of your particular study, what will we be likely to know that we didn’t know already? How much value might we place on that knowledge? How much time and effort did we expend to achieve it?’

Note that this does not require you to know the answer, but just to have an idea of the likely ‘shape’ of it. Example from physics…’to measure the gravitational constant…doesn’t mean you know its value already, but at least you know that you are looking for a number and you know its dimensions.

My first thought is – once again – directly in response to the nature of your comment: for someone who is unmistakably underwhelmed by the points put forward by this blog piece, you have persisted in commenting, contributing and inquiring within this discussion space. That is commendable – you are at least trying to understand why I think it is valuable. But this does offer something to suggest why this research is being conducted: why do people engage in online discussions? Particularly when the topic is not of primary interest/importance to them. Particularly when the discussion often transcends the particulars of the article/blog and becomes about more general ideas with respect to the value of certain research directives.

The very fact that you yourself have persisted with this discussion motivates me to continue doing such research. There is a question emerging in online journalism about the very point and value of online discussion threads and some publications have opted to remove the function altogether. But the simple fact that certain people spend so much time engaged in online discussion causes us to question what is actually achieved in such debates. Particularly when journalists and their colleagues are called upon to facilitate and moderate these threads. What can they tell them about their readership? Is is a good use of their time? Can media ‘users’ have a say in the nature and content of the news they have access to?

This of course is a much larger question than certainly I alone can answer, but there are those already engaging in the debate who feel that they are scientifically literate, that they have ideas and that they want to contribute in some way. Should we enable this? Does this go beyond the traditional journalistic model where we are left to consume – not contribute to – what is ‘newsworthy’?

Luke, maybe you could clarify what you mean in your second-to-last paragraph when you say “didn’t seem to be the scientific knowledge to solve the problem”. Do you mean scientific knowledge about AGW or do you mean solving the problem of there being so many disparate views?

I mean in relation to the AGW debate. (It may be worth pointing out that these discussion threads appeared prior to the latest IPCC report). My impression is that there is not some crucial scientific discovery that will provide the ‘missing piece of the puzzle’ here and resolve such disparity. The contributors to these discussion threads communicate in such ways that manifest as a difference in fundamental beliefs, as opposed to the levels of evidence that they are willing to accept or deny as a question of scientific validity. As such, I am less optimistic that scientific findings will put an end to the debate, based on what is already known and what could be known.

Thanks. Yes, I think I tend to agree. I think beliefs do play a big role in why there are such different views and I don’t think there will be some scientific finding that will resolve this is the near future.

The interesting question is then, I think, what value these debates actually have. In scientific terms, they may have no real value (at least not in terms of providing some kind of resource for those interested in understand the science). They may, however, illustrate important societal issues.

Indeed, core beliefs are clearly important. However, these may take various forms depending on who is involved in the debate and their particular standpoint.

So there could be:

Physicist might say: physics vs pseudoscience (sceptic blogs)

Sceptic/critic might say: observation vs models

Also, political left vs right

or even engineers vs climate science…!

All or none of these might be relevant at different times with different actors, but many of them represent different paradigms. One might attempt to try and identify the invocation of these, or other, beliefs, and see if they differ in terms of being open or closed to debate.

Yes, but what I was suggesting is that the existence of these different approaches/views implies – in my opinion – that there is little scientific value to most of these debates. For starters, why should someone’s political views influence their view of the scientific evidence. I can see that engineers and scientists (in general) might approach a problem in a different way but, again, given the evidence there’s no reason why they should interpret it differently. When a “sceptic” says observation vs models it normally – in my opinion – indicates they don’t actually understand the value of either. Scientists consider both and they influence each other (observations can constrain models, but models/theory are also needed to interpret observations).

So, all these different things are interesting but, as far as I can tell, do not contribute positively to the scientific debate. They may contribute positively to other aspects of the debate (i.e., what policy given the evidence), so I’m not arguing that there is no value to these debates, simply that the value with regards to the actual science is minimal.

[…] am interested in the use and abuse of comments left after online articles and blogs (see here and a blog post by Luke). So, I began to wonder what the function is of GIFs and related image-tools in reader […]

[…] The use and abuse of comments left after online articles and blogs is an interesting subject in itself so their use in science discussions may serve a bigger purpose than simply […]

[…] Polarisation or deliberation? […]