February 9, 2018, by Helen Lovatt

Hylas and the Nymphs are back

Edmund Stewart on why the recent removal of Hylas and the Nymphs was not merely clumsy but wrong

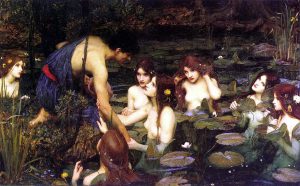

As has been widely reported in both the national press and this blog, Waterhouse’s masterpiece Hylas and the Nymphs was recently removed from display at Manchester Art Gallery in an attempt to ‘challenge a Victorian fantasy’ of the femme fatale. This was part of a so-called ‘take over’ of the museum by the contemporary artist Sonia Boyce. The gallery has claimed that it wanted to stimulate debate, yet that debate has been peculiarly one-sided: an overwhelmingly negative response has forced the gallery to return the painting. The public, who seemingly quite like art and the Pre-Raphaelites in particular, have taken back their museum. The curators who sponsored Boyce’s stunt are glibly pleased at the ‘fantastic response’ they have received and have again stressed that their aim was merely to prompt ‘a wider global debate about representation in art and how works of art are interpreted and displayed’. Those who opposed the painting’s removal may suspect that this statement is disingenuous or even dishonest.

It is hard to discuss the merits of a painting when you cannot see it and impossible to prompt genuine debate whilst simultaneously fostering ignorance. There was no debate or consultation prior to the picture’s removal. The contemporary art curator Clare Gannaway may, however, have revealed another motive in a statement reported by the Guardian. In discussing the gallery in which Hylas and the Nymphs hangs, and its title ‘In Pursuit of Beauty’, she confessed to a personal sense of ‘embarrassment that we haven’t dealt with it sooner’. You might have supposed she was referring to an unpleasant medical condition, rather than a display of art. One reason for the strength of opposition to Boyce and Gannaway’s actions is a fear that art is being censored as a political gesture or to suit the tastes of the modern curator. That fear may not be unfounded.

Art, and especially contemporary art, is being politicised, for the most part in a leftwards direction. If you doubt this, I would encourage you to peruse the bookshelves of the Tate or Tate Modern shop, as I did recently. There you will find some books on art, but also the complete works of Noam Chomsky and Naomi Klein, to quote only the most famous of today’s ‘thinkers’. A similar leftwards trend is also observable on university campuses. One study in the USA has claimed that Democrat voters outnumber Republicans by 11 to 1 among academic staff. At the same time, ‘no-platforming’ and ‘safe spaces’ are increasingly deployed to constrain free speech. Those speakers deemed politically incorrect have been met with abuse and even violence on campuses in America and the UK. It should be stressed, however, that this is not exclusively a vice of the left: the ‘alt-right’ would certainly censor if they could and many comparisons have been made with the Nazi seizure of supposedly degenerate art. And despite holding views that are diametrically opposed, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Germaine Greer have both been targeted by student protests. What they have in common is a profound belief in the importance of free speech and it is these values, rather than any specific ideology, that matter most in a democracy.

The removal of Waterhouse’s painting was notably opposed by people of all political persuasions, including the readers of the Guardian. These liberals and conservatives are seemingly united by a conviction that artworks should not be used as weapons in a culture war by any party. This is because art, unlike propaganda, has to be capable of more than one interpretation and it is for this reason that art critics and universities exist. Once you require art to serve a single agenda, then all art becomes suspect. Dmitry Shostakovitch’s commitment to developing uniquely Soviet music did not help him win the approval of Stalin for his opera the Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk or prevent its suppression. One may argue, of course, that the curators in Manchester were not acting under the direction of any dictator, but then intolerance does not always require centralised leadership. It is a matter of debate as to whether Henry VIII or puritan fervour was more responsible for the wholesale destruction of English medieval art. Significantly our age is also seeing the return of the popular ‘witch hunt’.

In forcing the return of Hylas and the Nymphs, moderates of all political persuasions have won a small victory. They will need to continue to oppose robustly and with determination censorship of all kinds in our art galleries and universities. For once you start a culture war, regardless of who wins, art will be the loser.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply