February 29, 2016, by Lucy

Sources in focus: estate correspondence

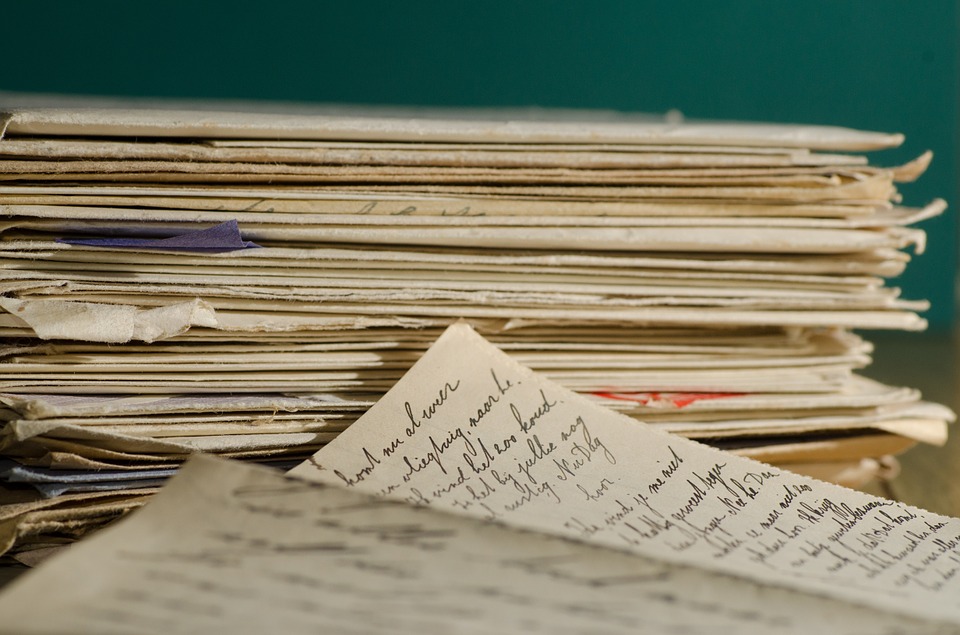

Since Christmas I’ve been spending some time over at the University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections, looking more closely at their weather-related holdings. A large proportion of the documents I’ve so far consulted have been letters.

Corresponding about weather

The weather is a popular topic of conversation, and, in a similar way to diaries, letters exchanged with loved ones (family members or friends), or between an employee and their trusted employer, or tenant and landlord often contain both descriptive accounts of the weather and its impacts, and personal reflections upon it, detailing physical or emotional effects. Correspondence is therefore, a widely recognised and valuable source for historical climatology. For example, Georgina (working with David Nash) has previously used missionary correspondence to explore climate variability in central southern Africa between 1815 and 1900, the content of letters enabling the construction of a chronology of drought and wet phases, as well as providing insight into missionary perspectives on drought and desiccation. There are some difficulties associated with the source – especially in ascertaining what the qualitative descriptions of the past are equivalent to in today’s terms, but there are many advantages too. In the vast majority of cases, a letter begins with a place or address, and a date, enabling a geo-referenced and precisely dated reconstruction of a weather event, exactly what we’re after for our database. Estate correspondence often also offers the further advantage of a long series of letters exchanged between the same people that can help us to get to know a little of the authors and their general relationship with the weather.

Papers of the Dukes of Newcastle

In this post I want to detail the type of weather information that can be found within the correspondence collections of large landed estates, and specifically within the papers of the Dukes of Newcastle. This collection has been designated as outstanding by the Museums, Libraries and Archive Council, reflecting its substantial historical interest for a whole range of topics. We have definitely benefitted from the detailed cataloguing of the collection that has been undertaken in recent years, the summary descriptions of letters often noting the presence of material relating to the weather, usually as it affected estate matters – whether it be building works, gardening, farming or travel.

The letters in the Dukes of Newcastle collection cover quite a wide geographical area, from the Nottinghamshire base at Clumber Park near Worksop, to other parts of the estate in Cardiganshire, Dorset, Kent, Lincolnshire, London, Surrey, Wiltshire and Yorkshire. All of those featured here come from the principal part of the archive known as the Newcastle of Clumber collection (Ne C).

Letters exchanged between Henry Heming and the 4th and 5th Dukes of Newcastle under Lyne (c. 1848-1860)

Henry Heming managed the Clumber collection of Newcastle estates, looking after rents and accounts for both the 4th Duke, Henry Pelham-Clinton (1785-1851) and the 5th Duke, Henry Pelham-Clinton (1811-1864). Heming’s letters regularly report on the weather as it was affecting works and harvests at Clumber and other Newcastle estates. When the 5th Duke was on a trip to Canada in July 1860, Heming adopted the practice of sending His Grace a weekly letter. Although Heming tried to be positive in his letters, the regular reports coincided with a very wet summer at Clumber and rain fell continually. On 17 August, Heming wrote to the 5th Duke:

“The weather is now the all-engrossing weather. Knowing the deep interest your Grace takes in all that concerns the welfare and condition of your dependents I do not refrain from informing you of the state of the weather about which so much anxiety is now felt by all classes of the people although to is very painful to write bad news week after week. There has been more rain since I wrote last week than in any previous week. The lowlands have been submerged and a great deal of the spoilt hay carried away. I have heard from Cromwell this morning that after three days fearful apprehension of a flood the river is going down…” Wheat was rotting and mildewed, and building works slowed. In the same letter Heming also refers to “repairs and rebuilding of places thrown down in the storms”, that presumably occurred earlier in the year (Ne C 13804/1-2).

A month later (14 September) Heming was finally able to, “inform your Grace of six days fine harvest weather”, though the operation was much later than the previous year, “In my own small concern I am more than six weeks later than last year” (Ne C 13808/1-2). From Heming’s correspondence we know that the summer of 1859 (and that of 1857) had been very hot and dry:

July 29 1859

My Lord Duke

… We have had very parching weather which has dried up all the grass & prematurely ripened the corn crops. We have had very little rain here. Harvest commenced generally last Monday. I am afraid there will be great complaints of the crops… The buildings & improvements upon the estate are progressing the weather being highly favourable with this exception that the men could not work so freely under such excessive heat… (Ne C 13782).

Hafod estate correspondence

Correspondence relating to the Hafod estate, a few miles from Aberystwyth, provides a nice linkage between Wales and Central England, two of our case study areas. Henry Pelham-Clinton (4th Duke) purchased Hafod in January 1835, the family already Welsh landowners at Dolycletwr in Cardiganshire and Cwmelan in Radnorshire. Henry took up residence at Hafod for parts of the year (he had recently left the house of Lords, his views out of sympathy with those of many of his peers, and also with those of his tenants and the Nottingham populace who resorted to rioting and an attack on the castle and his London residence). The Hafod estate had been unoccupied for some years before the Duke made his purchase and urgent building works were undertaken in 1837 and 1838 (Evans, 1995).

The early part of 1838 was not conducive to progress with outdoor work. On 1 February 1838, Samuel Heath (clerk of works, whom the Duke later dismissed) informed the Duke, “The weather continues so severe that the masons cannot work and very little had been done by the carpenters outside since my last. I have suspended several hands until the weather breaks and the timber is got in that they may be able to work outside at the shed &c. Several slates were blown off in various parts of the Offices during the late high winds…” (Ne C 8428).

On 26 February John Lown (the bailiff in charge collecting farm rents) wrote,“The weather has been very severe this last fortnight, frosts & snows. Your grace the weather has now changed & I fear we are going to have some cold rain, it is very rainy & stormy today. The turnips your Grace are a good deal injured by the frosts & there is a great complaint of a many potatoes being spoiled in the hills by the severe frosts” (Ne C 8429/1-2).

The following year, on the 14 January 1839, a hurricane struck the estate plantations (there was an abundant demand for timber from the local lead mines) as Alexander Williamson relayed to the Duke, “In the whole there are about 360 larch, 16 spruce and scotch, 12 oak, 24 other trees consisting of ash, beech and birch in different parts of the woods. The whole are among the largest dimensions upon the place but with the exception of the larch will not be found wanting as they are mostly from the back parts and centre of the woods where young ones are coming on to supply their places” (Ne C 8672/1). The winter of 1838-39 was also cruel to the sheep as John Lown wrote on 27 February, “…the weather has been of late very severe & very injurious to the sheep upon the Hills & has weakened them very much…” (Ne C 8456).

Conclusion

The examples featured here demonstrate how correspondence can be a rich source for UK weather history, both in building up a chronology of notable events and in understanding more about its impacts. Letters detail the effects of the weather on estate business and landscape but also hint at effects on people – tenant farmers struggling to make ends meet in years of poor harvests, labourers unable to work in poor conditions. Other letters in the Dukes of Newcastle papers describe impacts on personal health and wellbeing.

I hope to visit the team in Aberystwyth in April and so will be looking out for materials relating to Hafod in the National Library of Wales – the image of the estate reproduced here is taken from their collection. The majority of the Hafod estate is now owned by Natural Resources Wales who we are working with within the project.

We will be showcasing more of the materials from Manuscripts and Special Collections in an exhibition at the Weston Gallery at Lakeside on the University campus in December. You can also read more about in the manuscripts and special collections blog.

References:

- Endfield G. and Nash D. 2002 Drought, desiccation and discourse: missionary correspondence and nineteenth-century climate change in central southern Africa The Geographical Journal 168 33-47

- Evans E.D. 1995 Hafod in the time of the Duke of Newcastle (1785-1851) Journal of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society 12 41-58

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply