March 9, 2021, by Kathryn Steenson

Lenton Priory

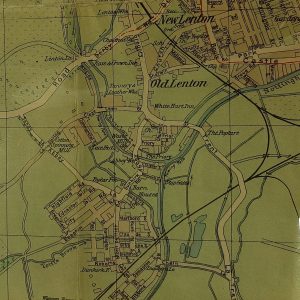

Did you watch The Great British Dig last week? Fronted by Hugh Dennis, a team of archaeologists excavated the gardens of homes built on the site of the long-gone Priory of Lenton, situated between the University Park and King’s Meadow Campuses. Lenton Priory itself is not exactly a mystery: this map clearly shows the site and there have been several archaeological excavations of the area, part of which is now under nearby residential streets.

The Priory was founded in the early 1100s by William Peverel, “out of love of divine worship and for the good of the souls of his lord King William” according to its charter (the text of which is reproduced in John Blackner’s A History of Nottingham).

At one point, Hugh Dennis visited Nottingham Castle to look out over the Priory site, about 1.5 miles away. The area has obviously become considerably more built-up, but the Priory would have been an immensely imposing building even from that distance.

We don’t have any images of the Priory from the Castle, but we do have one of the Castle from the Priory’s rough location. There was a coffee house (now the White Hart pub) on what is now the other side of the road from the Priory site, and even though the image was printed 200 years after the Priory was dissolved, it gives a real sense of how rural the area was and how impressive the Priory must have been.

North East View of Nottingham from Mr James’s Coffee House, from Blackner’s A History of Nottingham, c.1815 (Ref: EMSC O/S Not 3.D14 BLA)

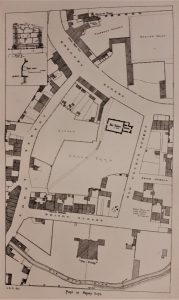

Map of the Priory site showing the graveyard, from Godfrey’s ‘History of the Parish and Priory of Lenton’, 1884 (Ref: EMC NOT4.P14.GOD)

Lenton Priory was repeatedly in trouble for the whole 400 years of its existence. The Mother House was in France, and allegiance to a foreign country would later cause the monks problems when the two countries were at war. There was also a dispute over the lands and endowments granted (or not) to the Priory as various nobles fell in and out of favour with the monarchs and accusations of fraudulent charters made. Consequently, it’s financial fortunes sometimes veered wildly from crippling debts to being amongst the richest Abbeys in England. In 1538 it was one of the first to be disbanded, in spectacularly bloody, style during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, with the Prior Nicholas Heath, several of his monks, and a handful of local labourers all publicly executed.

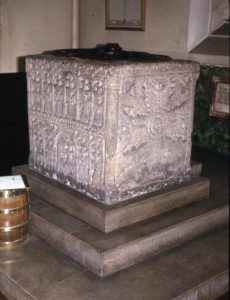

Some of the Priory buildings were pulled down and the stone reused, but enough remained for it to have sporadically been used to hold the Peverel Court and Nottingham Assizes, when outbreaks of disease made travelling to Nottingham unwise. By the mid-17th century, the buildings were largely tumble-down ruins, but the gatehouse survived until the 19th century. In 1802 William Stretton bought part of the Priory’s site to build a house, but not before he conducted a fairly extensive excavation and found several pillars and a beautiful 12th century Norman font, which was transferred to Lenton parish church a few hundred metres from the Priory’s site.

One of the remaining piers of the apsidal arcade of Lenton Priory, located at the corner of Priory Street and Old Church Street, 1966 (Ref: Mu B 183)

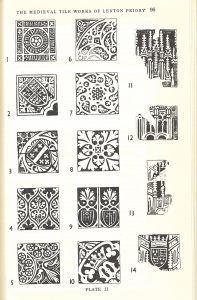

Cluniac monasteries are notable for being highly decorated, and many of the decorated tiles discovered on site were made in the formerly lost village of Keighton. This was only rediscovered in the 1940s, right in the heart of University Park Campus, and we covered the medieval village and its links to the Priory in a previous blog post.

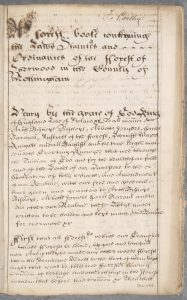

Supplies of clay and timber came from Sherwood Forest. Today, the forest is about 20 miles or so away from the Priory site, but six hundred years ago, the forest covered almost a fifth of the county and began almost at Nottingham’s city walls. The main London to York road, the Great North Way ran through the forest, so the labourers and tradesmen travelling to and from the Priory would have had company. The travellers were a tempting target for thieves, and no programme featuring Sherwood Forest would be complete without its most famous resident, Robin Hood. Forests were areas of land subject to Royal laws and reserved for the Royal hunt. Miles of dense tree cover are no good for hunting on horseback, and so there were areas of scrub, heath and even villages. Forests were not ‘wild’ either, they were carefully managed. The laws were written down in forest books, and included copies of statutes, rules and ordinances, and referring to matters such as the status of people living in the forest – and plenty of non-outlaws called Sherwood Forest home – felling of trees, hunting of animals, and boundary marks are discussed. Nottinghamshire’s woodlands were the subject of our exhibition, Sylva, and most of the images, information and talks from it are on our website.

One of the people in charge of keeping these rules would have been the chief law enforcement official at the time: the Sheriff of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests, a position William Peverel himself had held. The programme mentioned Philip Marc who, along with his deputy Eustace of Lowdham, were among the people the wicked Sheriff of Nottingham was alleged to be modelled on. These two men held office in the early 13th century and were deeply unpopular, to the extent that the Magna Carta presented to King John specifically called for Marc’s power to be removed.

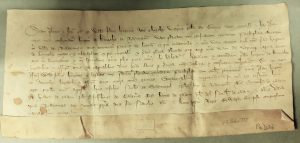

We have a handful of deeds witnessed by Marc and Eustace, and neither fell from status for long, and in fact Marc was wealthy enough that he left a gift to Lenton Priory in exchange for burial in the grounds and prayers for his soul. You can find out more about Robin Hood, and the contenders for the Sherriff, in this programme we made with the BBC World Service.

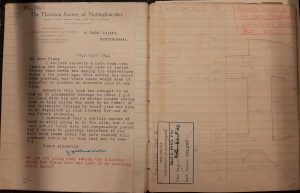

One of the final excavations took place in the 1930s. The survey contained in this volume was made by Arthur G. Powell, a student at University College, Nottingham who graduated in 1937. In 1935, he worked with Herbert Green on the excavation. Although the pencil is faded, the first page is headed ‘Revised survey of the chief excavations. Lenton Priory. 30/12/1935. A.G.P. – D.R.S.’ Other dates in the volume show that it was added to in February and July 1936 with pencil diagrams and measurements of areas of excavation, and an ink plan of the North Transept.

These are just a few items relating to the various people and places mentioned, and of course of Lenton Priory itself, which include deeds, archaeological records, newspaper clippings, histories, and even a published transcription of the Priory’s accounts from the 1290s, which can be found in the online catalogue. These are all available to view by appointment in the Reading Room at Manuscripts & Special Collections, a mere 15 minute walk from the site of the Priory itself.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply