September 28, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

The Missing Medieval Village of Keighton

Those of you familiar with University Park campus, especially the area just behind Lakeside between the Portland Building and the Science Park, will probably have seen Keighton Hill and Keighton Auditorium, even if you weren’t aware that they are named after the village that stood there 600 years ago.

This image on the left is a photo of the campus in the 1950s, with the Biology buildings that helped uncover many of the archaeological sites, compared with a modern day satellite image. That green hillside in the middle and the buildings to the top centre is essentially the site that we’re interested in.

But until the University started building the campus, the village was known about from documents, but nobody knew where exactly it was. It might seem surprising that an entire village can go missing, but it’s actually pretty common. There are well over 1000 abandoned villages recorded in Britain, most abandoned in the 14th century. A combination of repeated widespread famine caused by poor weather and then the Black Death reduced the population to the extent that some villages simply became unviable, especially those in areas where the soil was already very poor.

Keighton wasn’t mentioned in the Doomsday book of 1086, but it does make an appearance in some 13th century deeds. This is from a gift of land – not a gift as we understand it, because money changed hands – between John Passeys and Ralph de Wilford. It’s functional rather than fancy, and is written in Latin on animal skin. It’s dated 11 May 1276 and it’s from our Middleton Collection, and is not only one of our earliest documents in Manuscripts and Special Collections, but it’s the earliest mention of Keighton or Kiketon as it’s been spelled here.

The acre of arable land being gifted lay between the land of Hugo Stapilford on the south and that of Reginald Passeys on the north, both abutting the road to Kiketon. This is a standard way of describing land in legal documents, and is fine you know where Hugh of Stapleford’s land is, but the moment you start losing those references, you lose the locations. So this doesn’t actually help us pinpoint where the road to Keighton is. All it can tell us is that the road was well known enough to be considered a reliable boundary.

Apart from a few deeds, there isn’t really much mention of Keighton. People would occasionally theorise about where it might be, and they were impressively accurate with one antiquarian writing that “The village of Keighton or Kirkton, appears to have occupied the site between Spring Close and Highfield Park, on the slope of the hill on the south side of the road to Beeston, known locally as Cut Through Lane”. And that the meadows on the hillside that sloped towards Tottlebrook were once known as The Keightons. Another scholar based his impressions from surviving Anglo-Saxon and early Norman settlements: this site was above the flood levels, the slopes were well-draining and good for ploughing, and it neatly intersected with roads from nearby settlements at Chilwell and Beeston. These settlements usually have a cross roads, with one track for animals from the riverside meadows up past the houses to the arable fields, and another, often gravel road running across between villages. In the case of Keighton it was suggested that the very ancient road of Cut Through Lane could have been a connecting road.

And even if we had found it, we might not have been able to say much about the village life. Medieval archaeology in the 19th century was all about castles and monasteries. Plenty of work was done to find out about site layouts and buildings but until the rise of social history as an area of respectable academic study, there was little focus on the lives of the people who lived there.

The village was in the possession of Lenton Priory, which had been founded by William Peveral in the early 1100s. Its mother-priory was in France and many of the 25 monks themselves were French up until the late 14th century, which was all well and good except when international relations between England and France were strained, at which point its allegiances became slightly more problematic and this usually led to the priory having to pay out large sums of money. Initially quite well-off, towards the later years the Priory was constantly and heavily in debt.

Keighton was one of several villages that contributed tithes and dues to the Priory, but it’s apparent that the village was never very large, and was probably established predominately as an industrial site for the Abbey. From the quantities recorded as payment we know that both the number of tenants and the quantity of land they held was small. Cottagers in Keighton paid considerably less rent than those in the surrounding villages. Not every payment to the priory was of money: grains, lambs and physical labour were all acceptable. Keighton tenants would have owed their labour to help with sowing and harvest, for example three mornings a week from October to February and in May and June. The records are incomplete and unclear, but it may have been as a few as 8 tenants who owed this, which again shows just how few people overall would have lived there. Despite its failings, the archival record gives us insight into daily life. For example, in 1297 the harvest failed due to a wet summer, with so much rainfall that men had to be employed to carry the hay out of the water and spread it out to dry. lt must have been a huge worry for the villagers who faced a winter of food shortages and hunger.

Photograph showing Nottingham University College lawns being ploughed by a tractor for the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign, 20 March 1940, with the lake in the background. (Ref: UMP/2/1/40/1)

And it was food insecurity that led to a breakthrough was made in 1940. It was a complete accident, the field was being turned into allotments to grow cabbages and carrots as part of the Dig for Victory campaign during WW2, when an academic, Alice Selby, dug up fragments of burnt bricks and glazed tiles, indicating a kiln. There were other, slightly more pressing matters, to attend to at that point, so serious excavations didn’t get underway until the 1950s.

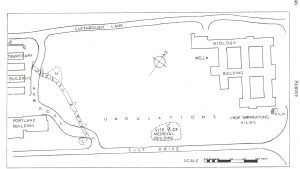

Unfortunately, not all the excavation work was prompted by pure archaeological curiosity, because the site was being redeveloped. This is a plan showing the area that was investigated, and is the same as area from the satellite image shown earlier, with what was then the brand new Biology building was under construction on the right. Flat stones, a doorway, and some domestic cooking pottery indicated the site of a medieval cottage, and then a medieval track was uncovered, a gully some 5ft wide and filled with small stones to create a solid surface. Unfortunately, the archaeology team had only a few weeks to excavate all of this, as the University was building a new road over the top of it and using the rest of the site for temporary contractors’ buildings. Indeed a second possible medieval cottage, at site marked N, on this survey was briefly uncovered but there wasn’t time to conduct a full investigation, and part of one of the kilns that was excavated is now underneath the wall of the biology building.

So limited though it was, it’s pretty safe to say this was the vanished village. But the vast majority of what was uncovered provided evidence of at least three industrial kilns, which is not a typical feature of a medieval village. So why kilns?

Lenton Priory was only half a mile away, and it’s almost certain that the tiles used to pave the floor of the chancel in the priory were made at Keighton. The soil contains a lot of clay, and there was plenty of water available from well and the streams – there’s a reason why people chose to build an ornamental lake on campus. The medieval well originally excavated in the 1950s was 22 feet deep and couldn’t be properly excavated because the water table was so high. Another attempt in the 1960s was more successful, and it showed that the well had been used in the 1200s to mid-1300s when it had silted up. It was then used as sort of communal rubbish dump for broken pottery – jugs and cooking pots, mostly, with evidence of oats and barley being eaten as part of a staple medieval diet.

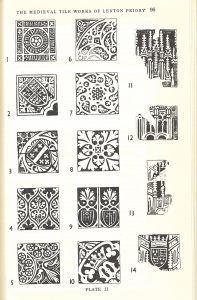

But these cooking pots weren’t being fired in the kilns on site. Instead tiles were found, a mix of plain roof tiles and decorated floor tiles, made of red and white clays, most of which were defective or damaged and had clearly been thrown away. One of the most significant finds was a tile with the date of 1457 or 1458 on it. Medieval tiles were made by pressing clay into wooden moulds. Any decorations were added by using a wooden die to impress the image onto the clay, which was then filled in. Glaze, often green but sometimes yellow or brown, was added to air-dried tiles and then when the tile was fired, the glaze melted onto the clay. You can see here the huge variety of designs that were made, and if you look at the number 10 you can see a line where the die was slightly defective. This was found on multiple tiles, so clearly the same slightly broken die was used repeatedly. The archaeology points to a site that was in use until the late 15th or early 16th century, and we know that Lenton Priory was dissolved by Henry 8th in 1538. It seems likely that the tile works at Keighton were a temporary operation, with the workers setting up kilns specifically to produce tiles needed locally and then leaving. The final mention of Keighton in the monastic records is in 1387 when the five remaining houses were little more than ruins described as being ‘as much in want of repairs as of tenants’. The village is likely to have been abandoned before the tile work ceased, and perhaps some of the buildings could have been repaired well enough to be used by them.

But the even after the kilns were abandoned, the clay was still being excavated from the site, with the spoil dumped on top of the kilns. It took nine months for the archaeologists to dig down through the 6 feet of waste to find a second kiln, and they probably wouldn’t have found the third kiln at all if a bulldozer hadn’t gone through the site.

Eventually Keighton stopped being used even for clay. Further excavations in 2001 revealed a possible area of ridge and furrow cultivation on the upper slopes of the hill, and that after being abandoned, the site was purposefully covered with ploughsoil and used for agriculture. Perhaps the odd bits of tile and pottery churned up by the plough kept knowledge of the village site alive for a few more generations, but farming stopped around the 16th century. Within two or three hundred years it had almost vanished from local memory and, with the exception of a few extraordinary and unnatural undulations in the ground, largely gone from the landscape. In the 1950s and 60s the archaeologists envisaged further work would be undertaken to unearth more of Keighton and trace where the main street and other houses were. An excavation in 2000-2001 was carried out and the findings printed in volume 105 of the Transactions of the Thoroton Society, which can be read in the Reading Room.

The rather scant documentary evidence here is available to view in the Reading Rooms at Manuscripts & Special Collections. Apart from the building and road names, the history of Keighton is marked by a small information plaque on East Drive, overlooking the grassy slope where part of the village once was, and the Archaeology Museum at Lakeside has a selection of artefacts from the site. The Museum will reopen soon, but in the meantime, on your next to Highfields and Lakeside, take a look and maybe try to imagine what it must have looked like five hundred years ago.

You imply there has been no excavation there since the 1950s, though my understanding is that the Archaeology department has occasionally used the site for student training excavations not so long ago. Don’t know what if anything they found though.

Hi Judith,

Yep, the site was excavated as recently as 2000, by Lloyd Laing. His findings are published in the Thoroton Society Transactions for 2001 (volume 105). That was just a bit too late for my undergraduate years, so I wasn’t involved in the actual dig, but I did a project with Nottingham City Museums’ “Access Artefacts” team about 15 years ago which included some analysis of the findings, and there’s a whole case dedicated to Keighton in the University Museum!

Further details: I’ve just looked back at my notes and found that further excavations were done in 2006, although at the time I was writing (2009, so not 15 years ago at all!) the reports hadn’t yet been published.