April 2, 2019, by Kathryn Steenson

In Sickness and Incest

On the 9th June 1732, Edward Robinson and Martha Robinson of Heanor were married in St Alkmund’s, the 12th century parish church of Duffield in south Derbyshire. At the time, the happy couple were living 18 miles away in Beeston, a few miles from Nottingham city. Perhaps they married there because Martha was originally a Derbyshire girl.

It’s also possible that they hoped the distance would keep the wedding a secret.

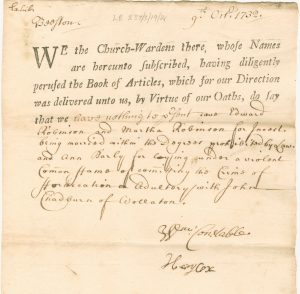

If that was the case, they were to be disappointed. The ecclesiastical authorities quickly found out and in October 1732 the Robinsons were ordered before the church courts. Their offence? Incest.

‘Incest’ had a much broader definition in the 18th century than it does today, and did not necessarily mean that the two were blood related. The Robinsons were accused under the ecclesiastical definition as laid down in the Table of Kindred and Affinity (1563). This was supposed to be publicly displayed in every church, although in an era with low literacy levels it might not have been terribly helpful for parishioners. The church forbade marriages between people ‘within the prohibited degrees’, which included first cousins and the siblings of one’s deceased spouse.

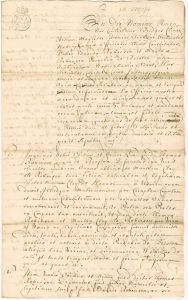

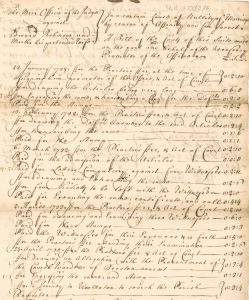

Church courts dealt with moral and spiritual offences, not criminal matters. The initial churchwardens’ presentment bill, which was the first written notice that action was going to be taken against somebody, gave no further details about how the Robinsons were related, but later documents do. Due to the complexity of the case and the seriousness of the potential outcome – i.e. the dissolution of the marriage – the case was referred up the church court hierarchy, and thus generated more paperwork. In January 1733, the articles of the case laid out (in Latin) the circumstances and filled in some of the missing details. Martha Clay, daughter of Robert Clay of Heanor, married Thomas Robinson, son of Edward Robinson, in 1722. They had children and lived in Beeston together until Thomas’s death in about 1729. It goes on to say that it was a ‘common fame’ (i.e. well known and the subject of gossip) in Beeston that in 1732 Martha and Edward had solemnized a ‘pretended marriage’ and consummated it, thereby putting their souls in grave danger and setting a bad example for other Christians.

We don’t have parish records here in Manuscripts & Special Collections (they are at Nottinghamshire Archives) but a quick check of an online index of transcriptions shows a baby girl, Ann, was baptised in Beeston in 1728, the daughter of Martha and Thomas Robinson, a tailor.

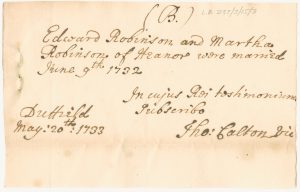

The same index also shows that in September 1732 Mary Robinson was baptised, the daughter of Martha and Edward, also a tailor. If this is the right couple, it would certainly explain how the neighbours knew about their sexual relationship. Three witnesses were called to give depositions, unfortunately now lost, but the certified copies of both marriage entries from the parish registers that were presented as evidence do survive. It was clear that Edward was Martha’s former father-in-law and that the two had married despite being too closely related under church law.

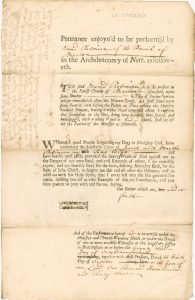

They don’t seem to have offered up much of a defence, and the verdict was a foregone conclusion. The sentence was formally given in July 1733: after 13 months, their unlawful and incestuous marriage was declared void and the two were ordered to live separately. This was not the only punishment imposed on them. Partly as a warning to others, they were expected to publicly repent by performing a penance. On 14 October 1733, they stood before the congregation in Beeston parish church, barefoot and bareheaded and wrapped in a white sheet, and recited the schedule of repentance as provided by the church court. The statements were then were endorsed with the signatures of the vicar, two churchwardens, and three other parishioners, certifying that the penances had been performed.

The third and final part of their punishment was to pay the court costs of £5 10 shillings. This covered the costs of drawing up the documents, travel costs to see the parish registers, even wine for the sessions. The amount was equivalent to about two months’ wages for a skilled tradesman; an enormous sum, assuming Edward was a tailor. In November the court found them in contempt by failing to pay without giving a reasonable excuse, and the couple were excommunicated. This penalty meant they could not receive holy communion, and were technically also subject to civil restrictions as faithful members of the congregation were meant to limit interaction with them. Excommunication could be reversed, if the person repented and carried out their punishment, but the schedules of absolution for the 1730s are fragile and we haven’t been able to check if the Robinsons are in them.

Eight months after Martha and Edward were forcibly divorced by the courts, a Robert Robinson was baptised in Beeston parish church. His mother’s name was given as Martha. His father’s name was left blank, as was standard for babies born out of wedlock.

This bundle of case documents, AN/LB 237/3/14-19, is part of the Archdeaconry Court collection. The originals are available to view in the Reading Room at King’s Meadow Campus. For more information about the archives and rare books here, you can read our newsletter Discover or follow us @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply